A humorous look at some of the greatest unacknowledged feats of Royal Society science, including the best scientific one-liner and the most unlikely invention.

The Royal Society has a long history of recognising excellence in science and awarding medals to worthy recipients. A quick look through the archives, though, suggests that scientists have often dedicated their most strenuous efforts to completely different fields in which no prizes have ever been given... until now. It’s Friday afternoon, and while our Olympians’ sporting achievements are being celebrated, let’s take a moment to consider the greatest unacknowledged feats of science (with a distinct Royal Society bias).

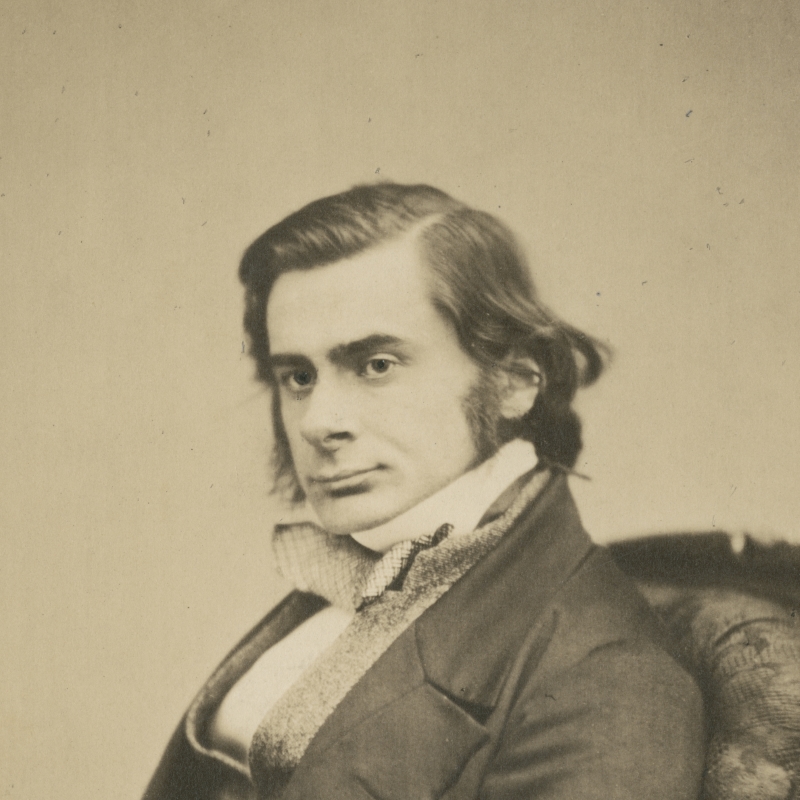

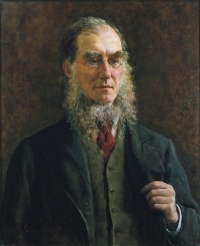

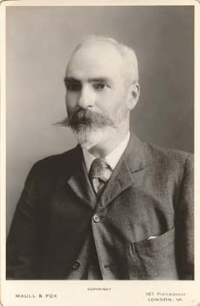

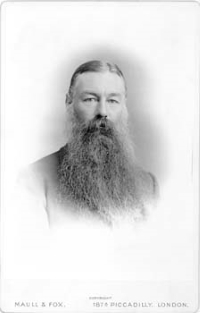

The first prize is inspired by a certain British cyclist and is awarded for the best scientific whiskers. The field for this award is vast, and especially amongst the Victorians competition in the category is stiff (and bristly), with Royal Society Fellows Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, Arthur Robertson Cushny and Conwy Lloyd Morgan all competing at the highest level:

Joseph Dalton Hooker

Arthur Robertson Cushny

Conwy Lloyd Morgan

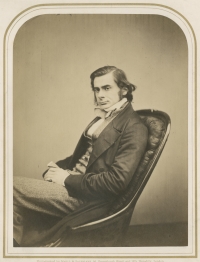

However, in recognition of his understated yet strangely compelling side-whiskers, the award goes to a young and brooding Thomas Henry Huxley:

Thomas Henry Huxley

The next prize recognises the efforts of those involved in scientific feuds (a perennially popular form of scientific entertainment), and is awarded for the best (possibly apocryphal) scientific one-liner. Perhaps the most famous is Newton’s comment to Hooke about standing on the shoulders of giants. Posterity has suggested this was a joke about Hooke’s stature, but if that was Newton’s idea of a joke then it’s just as well he stuck to science as a career. More amusing, and therefore more deserving of this award, is John Woodward’s taunt to his fellow physician and Royal Society Fellow Richard Mead, on the eve of their duel, that he would rather die by Mead’s sword than by his medicine. Ouch!

Following on from this, in recognition of the fact that the road to scientific success is rocky and occasionally strewn with tacks, the third prize is awarded for greatest scientific perseverance in the face of provocation. An extremely challenging category to judge, the competitors include luminaries such as Galileo and Darwin, both of whom ran into difficulties with the Establishment; Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, and other early Fellows of the Royal Society, who were routinely mocked by London satirists and playwrights for their investigations of fleas, lice, and the weight of air; and probably a great many other deserving contenders. On this occasion though the winner is Mary Somerville, who seems to have accepted with calm grace the fact that despite her mathematical prowess she would only ever be represented at the Royal Society by a marble bust commissioned by the Fellows:

Marble bust of Mary Somerville, commissioned by the Fellows of the Royal Society

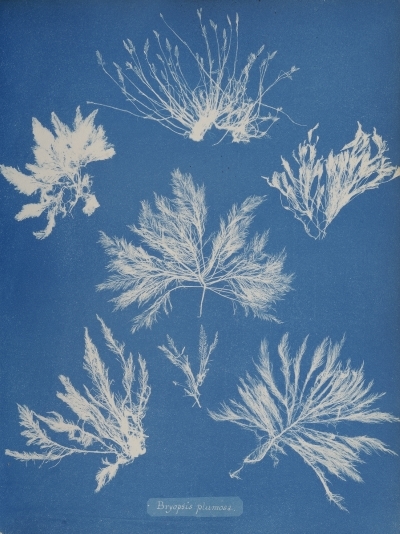

In recognition of the wide range of activities that make up ‘science’, the fourth prize is for best scientific collection. Again, there is a very strong field for this award, in both the individual and institutional divisions. An early entry comes from the Royal Society, whose 17th century ‘Repository’ contained such entertaining and educational items as a mummy, gloves made from spiders’ silk, and a ‘giant’s thigh-bone’ (re-classified by Dr Nehemiah Grew as an elephant bone). Individual scientists have curated more specialised collections, including Walter Rothschild’s 300,000 birds’ skins, and his brother Charles’s impressive collection of fleas. The award, however, goes to Anna Atkins, who not only assembled an extensive collection of algae, but proceeded to publish over 400 cyanotype impressions of her seaweed samples, becoming the first person to use photography to illustrate a book:

Cyanotype impression of algae by Anna Atkins

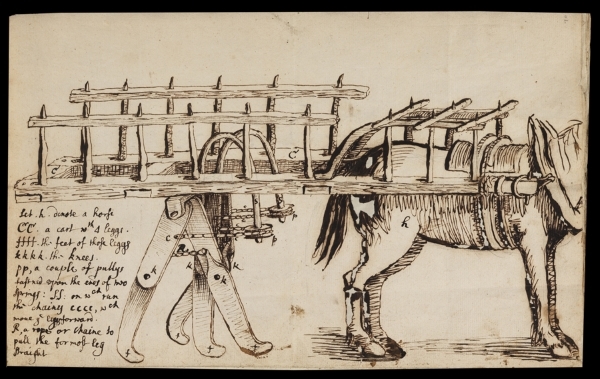

The final prize is awarded for most unlikely invention, and there is only one serious contender – Francis Potter FRS, for his cart with legs (with a little help from Robert Hooke, who drew the diagram):

Robert Hooke’s drawing of Francis Potter’s design for a cart with legs

It was Hooke who pointed out that the cart would have difficulty reversing, which may have been why the design never went into production.

That’s it for my brief round-up of unsung scientific achievements, but if readers have further suggestions I look forward to hearing them!