"Petiver has tended to be overlooked by historians of science, even though there is a wealth of fabulous archival material"

The latest Special Issue of Notes and Records, guest edited by Richard Coulton and Charles E Jarvis, marks the 300th anniversary of James Petiver's death. We asked Richard some questions about their research.

Could you give some background about the origins of the James Petiver special issue?

We’ve both been fascinated by Petiver’s life as a natural historian and collector for many years. Charlie Jarvis worked for a long while with the Sloane Herbarium at the Natural History Museum, which is widely known as one of the most important global deposits of early botanical material. What hasn’t been so well understood is Petiver’s contribution to the Herbarium: around one-third of the volumes comprise specimens of plants that either he gathered himself or acquired from other botanical collectors. Meanwhile I’ve been interested for some time in Petiver’s role within eighteenth-century natural history networks – both global and local (to London) – that connected medical practitioners, merchants, scholars, seafarers, colonial administrators, and many others. The scale and diversity of this network has never been comprehensively researched despite its rather extraordinary international and social reach.

So we have both felt for some time that Petiver has tended to be overlooked by historians of science, even though there is a wealth of fabulous archival material, particularly at the British Library and the Natural History Museum, but also at the Royal Society, the Guildhall, and elsewhere. We knew of a few other like-minded researchers and decided to organise a conference to mark the 300th anniversary of Petiver’s death in April 1718. The event was generously hosted by the Linnean Society on 26 April 2018 and this special issue features some of the excellent contributions that were presented on the day.

Moss specimens received by Petiver from French botanist Sébastian Vaillant. Image reproduced here with kind permission of the Natural History Museum, London.

How does the research contained in this special issue change our understanding of Petiver’s contribution to the many practices in which he participated?

We’ve called this special issue, like our conference in 2018, “Remembering James Petiver”. Our idea is to “remember” Petiver actively, playing on the sense not just of bringing back into memory something that’s been forgotten, but also of putting back together something that’s been “dismembered” – in this case Petiver’s archive, and with it the quality of our historical understanding of his life and legacy. All of the contributions in this special issue conduct primary research that reconnects archival traces of Petiver’s activities: as an author, an apothecary, a correspondent, a collector, a natural scientist, a networker. These aspects of Petiver’s identity intersected with and informed one another.

As the essays by Kate Murphy, Katrina Maydom, and Alice Marples all show in various ways, Petiver’s professional connections, labour, and knowledge as a pharmacological retailer importantly informed his reach, collections, and understanding as a natural historian. At the same time it’s a pleasure to include research from two esteemed natural scientists, botanist Charlie Jarvis and entomologist Dick Vane-Wright, who bring a type of expertise to bear upon Petiver’s collections and publications that humanities trained historians of science like me can struggle to achieve. Their work reconnects components of Petiver’s now-dispersed material specimens, manuscript records, and published output, demonstrating his real abilities as a natural historian.

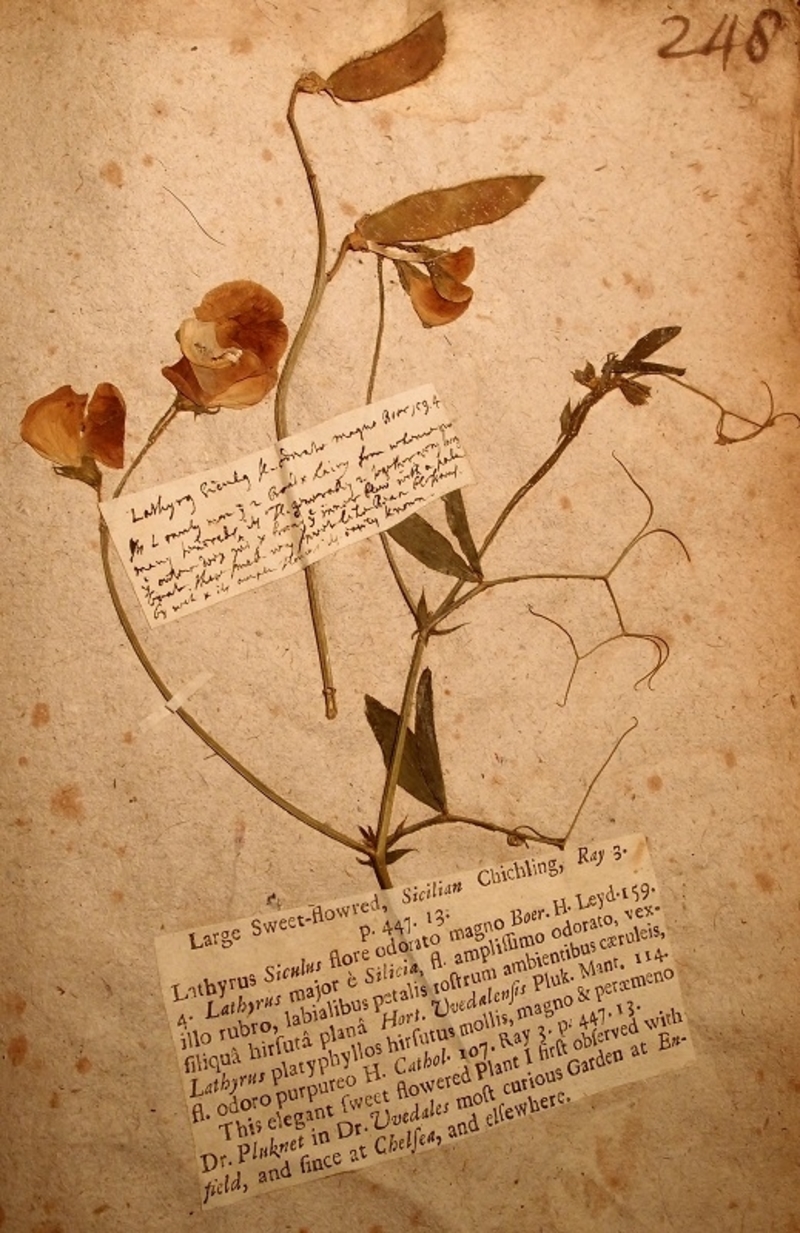

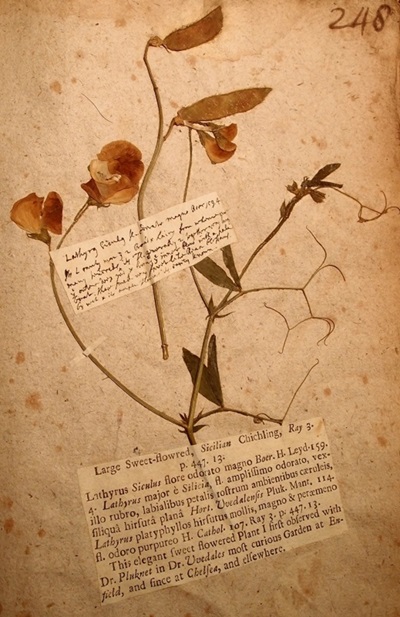

An early cultivated specimen of a sweet pea (Lathyrus odoratus) from Petiver's herbarium. Image reproduced here with kind permission of the Natural History Museum, London.

How do you hope the reputation of Petiver will change?

In the past when Petiver has been the object of study – at least until the start of the present century – historians have been hampered by previous assessments of his character and capacities. These haven’t always portrayed him in the most flattering (or, more importantly, the most objective) of lights. Most famously his friend Hans Sloane posthumously complained that the poor state in which he inherited Petiver’s collections significantly retarded his own research for the second volume of the Natural History of Jamaica. Petiver was also satirised in publications during his lifetime and caricatured very funnily but rather unfairly in the travel diary of Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach (a Prussian intellectual). Later generations of scholars and archivists seemed to rely on these assessments to shape their own evaluations of Petiver’s specimens and publications rather than attending as directly as they might have done to what he actually achieved.

So we hope our research will help to re-evaluate Petiver through the specific focus we’ve brought to bear upon his practices as a natural historian, social networker, published writer, and medical practitioner. In each of these zones of activity a close study of the historical record shows him to have been remarkably innovative and able.

Of course, we’ve tried hard not to fall in love with our subject. We don’t want to become sentimentally blinkered, which obviously leads to the wrong kind of historical revisionism. Certainly no-one will ever be able to rescue the reputation of his appalling hand-writing. And far more seriously, Kate Murphy’s essay reminds us importantly that Petiver was very much a man of his time in readily benefitting from contacts among slave traders and other agents of empire. It’s fairly clear, for example, that items in his Atlantic World collections were gathered by enslaved persons whose contributions were disingenuously and problematically overlooked both by Petiver and subsequent curators of his collections.

A dragonfly caught for Petiver by the ship's surgeon John Kirckwood near Angola on 27 August 1700. Image reproduced here with kind permission of the Natural History Museum, London.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about Petiver in this project?

Well, we’ve learned lots. At a fairly mundane level we’ve found out a little more about Petiver’s personal background. It now seems highly likely, for example, that he was born and bred in London despite his family’s Warwickshire origins. We’ve also been able to pinpoint the precise location of his shop on Aldersgate Street, in Petiver’s time “at the sign of the White Cross” but now a rather anonymous office block opposite the Barbican and sorely in need of a blue plaque!

I guess while all the essays in this special issue are excellent, two stand out as presenting research that’s very new to me. Katrina Maydom’s article is the first I know that deals with Petiver first and foremost as a trading apothecary rather than a natural historian. It was fascinating to learn that his professional records (now at the British Library) are as singular and informative for the history of medicine as his other personal manuscripts are for the history of science. Meanwhile, Dick Vane-Wright’s piece on Petiver’s Papilionum Britanniae (‘Butterflies of Britain’) proves that his scientific understanding of lepidoptera was incredibly sharp. Although many modern entomological concepts (such as polymorphism and polyphenism) were necessarily unavailable to Petiver, his observation of butterflies’ anatomy was so astute that he generated a comprehensive inventory that is tremendously close to modern species definitions.

Notes and Records is an international journal which publishes original research in the history of science, technology and medicine. Find out more information about submitting to Notes and Records.

Images: Reproduced by kind permission of the Natural History Museum, London.