Keith Moore takes a look at the contents of some unconventional paper collections, featuring the Witchfinder General and a large herring.

Like most cultural institutions, museums are having a tough time of it at the moment. Because their collections have been out of sight for some while, curators have been finding new and unlikely ways to engage their audiences online: from virtual learning to Museum Challenges. There have been all kinds of unconventional museums in the past too, and I’ve been looking at a few of the ones that called themselves museums, but which existed only on paper.

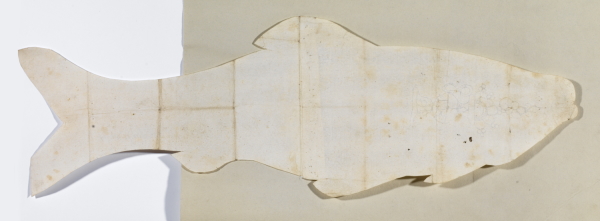

The Royal Society’s original seventeenth-century museum Repository is long gone, unfortunately, but there are one or two remnants of early objects in our collections. My favourite is the cut-out version of a large herring caught off Scotland in 1663 and forwarded to the Society by Sir Robert Moray (1608/9-1673). A pity you can’t see the fish itself, but the 19½ inch model is the next best thing, and presumably a lot easier on the nose in the days before rapid door-to-door parcel deliveries.

Fisherman’s tale: a 19½ inch herring from 1663 (RS.15183)

The Scottish fish appears alongside measurements for what was thought to be an anomalously large human child. Past accumulations of exhibits very often contained such extremes, many of which we’d find quite unacceptable as display content today. I’ve been learning that interest in the curious continued in print form into the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and again, we have a few illustrated examples, particularly reproducing biographies and prints of quite obscure historical figures. These were culled from rival ‘Wonderful Museums’, initiated by William Granger (fl.1765-1809) and by Ralph Smith Kirby.

William Granger’s The new wonderful museum and extraordinary magazine… was produced in association with James Caulfield (1764-1826) from 1802. The magazine resembles a random sampling of Wikipedia pages: it contained an eclectic mixture of ‘singular’ biographies, anecdotes, ghosts and oddities, often with illustrations redrawn from earlier engraved plates. These were the work of Caulfield, a well-known print collector and salesman as well as a printmaker and publisher. A random sample of the ‘Museum’ contents gives you something of its flavour: in the first volume, a brief note on Robert Boyle’s air-pump (p.90) is preceded by a biography of the allegedly 152-year-old Thomas Parr of Winnington and followed irresistibly (and unaccountably) by a description of ‘The remarkable dirty warehouse in Leadenhall Street’.

Folk horror: Matthew Hopkins, the ‘witchfinder’

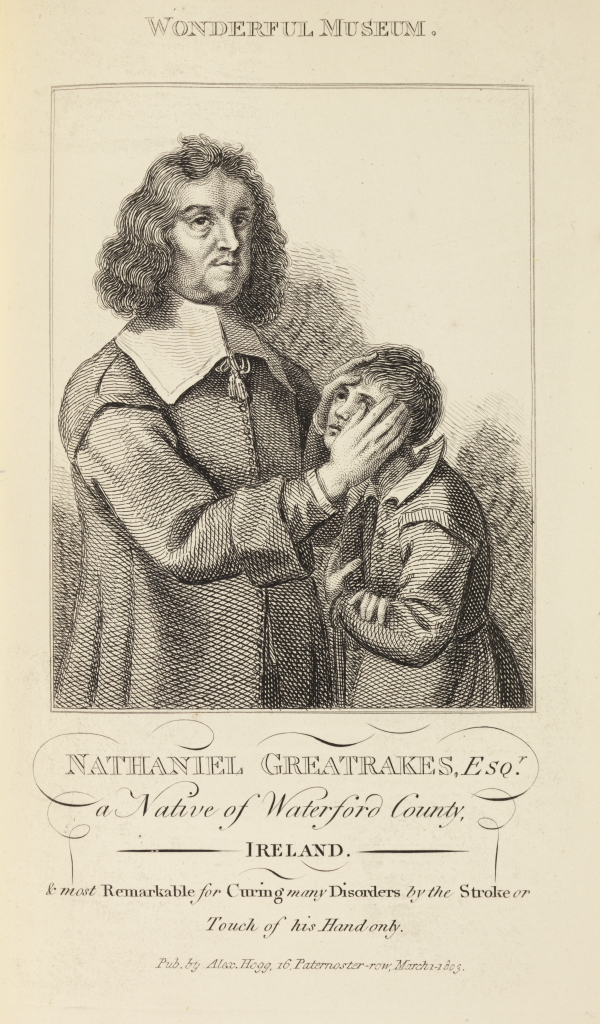

Among the engravings in the Royal Society’s collections emanating from Granger’s journal is one of Matthew Hopkins (d.1647), better known as the Witchfinder General of Civil War England (and played with movie gusto by Vincent Price). Granger’s journal has a surprisingly apt account of the notorious Hopkins’s methods, ‘such as who could not plead their cause nor hire an advocate, were the miserable victims of this wretch’s credulity, spleen and avarice.’ Similarly, we have Caulfield’s engraved version of the Irish faith-healer Valentine Greatrakes (1628-1682). The ‘stroker’, as he was known, was supposed to have laid hands on the future Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, and later visited London in 1666, coming into contact with Robert Boyle. Several documents associated with Greatrakes and the nature of his ‘miracles’ survive in the Society’s archives.

The ‘stroker’ Valentine Greatrakes (mistakenly named 'Nathaniel' in the caption) and patient

Granger’s ‘Museum’ wasn’t the only publication of its type. Ralph Kirby, who had apparently been employed by Granger, decided to cash in by setting up Kirkby’s wonderful and eccentric museum; or magazine of remarkable characters (1803, and in collected book form from 1820). He too dipped into varied topics, from the floating island of Derwentwater to the speed-walking exploits of Captain Barclay – Robert Barclay Allardice (1779-1854), whose thousand-mile epic walk of 1809 was fuelled by breakfasts of roasted fowl and strong ale. The journal also shamelessly reprinted material from the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions, including another ‘remarkable fish’, this time a whopping four-foot-nine specimen landed in Bristol in 1763 and described by James Ferguson. Until we can walk into a museum – soon I hope – such paper substitutes will have to do.