Virginia Mills finds cases of extreme fasting and overeating in Royal Society archives from the eighteenth century.

Watching The Wonder recently, it struck me that the film’s premise could have come straight from the archives of the Royal Society.

Based on the novel by Emma Donoghue, the film is set in Ireland in 1862, in a community still recovering from the Great Famine and grieving those lost. It concerns a girl who can seemingly survive ‘inedia’ (without eating or drinking). The fasting child is observed independently by a nurse and a nun to establish the veracity of her claim. The plot examines her reasons for fasting and her apparently miraculous survival, with perspectives varying from the religious to the scientific, pseudo-scientific (surviving on nutrition from the air) and psychological.

Specifically, the film put me in mind of accounts collected by Royal Society Fellows describing what we would now refer to as disordered eating. Sadly, these include numerous real-life cases of ‘fasting girls’, as they were known in the Victorian period, many motivated by religion, their survival awfully lauded as miraculous. The condition depicted in The Wonder, similar to anorexia nervosa but with a religious motivation, is known as anorexia mirabilis and goes back to self-starvation by nuns and religious women in the Middle Ages.

From extreme fasting to overeating, cases were reported to the Royal Society, with a particular prevalence in the eighteenth century. Sometimes sensational and often tragic, the accounts usually took the form of observations by local physicians, passed on to medical Fellows to be read at Royal Society meetings. Some cases were published in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions journal:

In 1776 a Dr Mackenzie reported the case of Janet Macleod, a woman in her thirties who after a series of seizures was left bedridden and partially paralysed. Though she would respond to those around her, she had no appetite and refused food and water. Her unwillingness to eat, combined with the apparent effect of a particularly bad lockjaw seizure, thwarted her desperate parents in their efforts to feed her.

Janet is supposed to have persisted without sustenance from 1763 to 1771, at which point on returning from their ‘country labours’ her parents found her out of bed, spinning and willing to eat small amounts of crumbled barley cake. One can’t help but speculate if she was always as bedridden as was reported, with her parents absent working the fields during the day and no diligent observers as depicted in The Wonder...

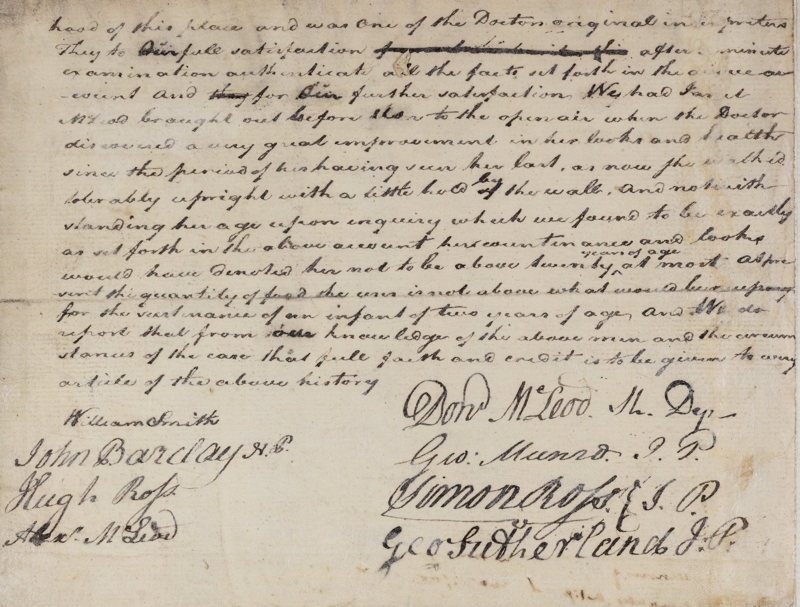

Dr Mackenzie recorded that he examined Janet on several occasions. He gave a medical history and description of his patient’s health and behaviour based on his observations and the testimony of her parents, the veracity of which was endorsed by eight signatories, from neighbours to the Deputy Sheriff. The report was sent to the Royal Society by the Lord Privy Seal of Scotland:

Mackenzie didn’t offer a diagnosis beyond identifying that the loss of appetite was preceded by seizures. Neither did he propose a recommended treatment, and only identified physiological symptoms; there is certainly no sign of an attempt to investigate a psychological cause. Anorexia is now recognised as a psychiatric disorder, but this was centuries away from happening when Mackenzie made his examination of Janet Macleod.

Historical diagnosis is problematic, but there are signs in Mackenzie’s report indicating that Janet may have been anorexic prior to her debilitating seizure: she never began menstruating, a clue perhaps to earlier signs of undernourishment. There are also links between hormone imbalance and unstable appetite, so there may have been a biological cause. Either way, the only treatment available to her parents in 1763 was to try to get Janet to drink holy water from a medieval spring at Braemar until she thankfully began to eat once more.

There are also eighteenth-century cases of ‘boulimia’ described in the archive. I was surprised to see the term in use in a paper dating to 1745 (L&P/1/389). However, these are not being identified as bulimia nervosa cases: the cycle of binging and purging/abstaining was not classified in psychiatry as an eating disorder until 1979. They refer to cases of ‘ravenous hunger’, the literal translation from the Greek, also called in some historical accounts ‘fames coenica’, meaning hunger pangs.

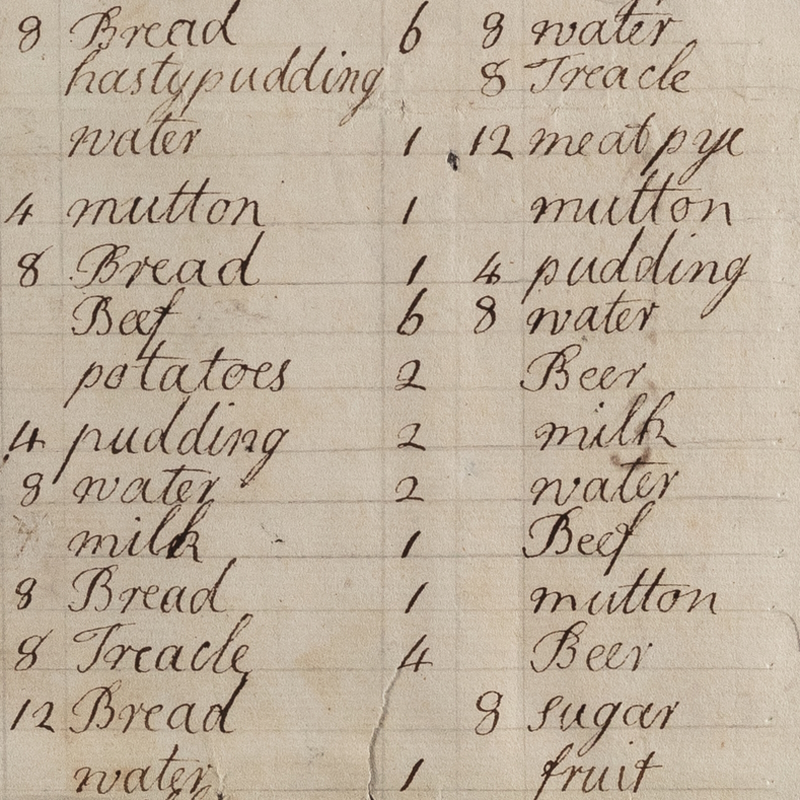

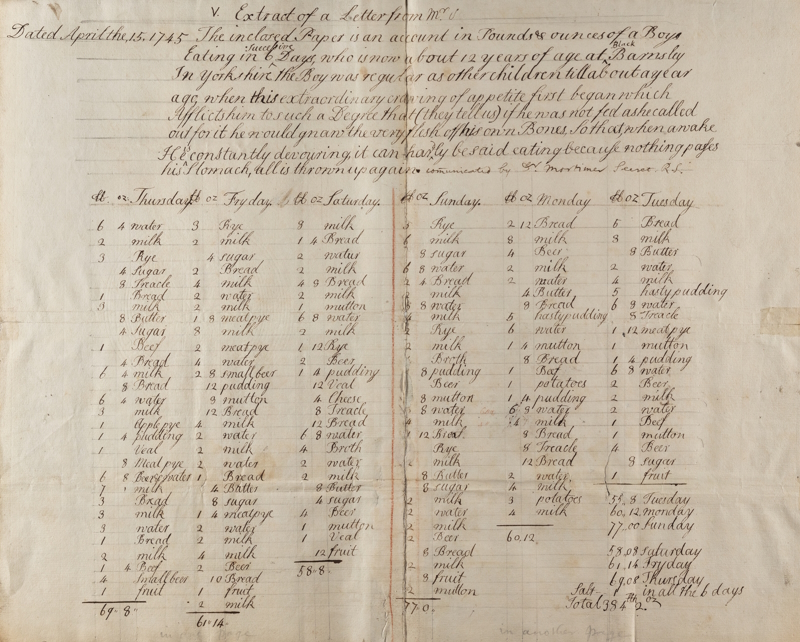

An account of Matthew Daking, aged about 12, includes tables listing everything the child consumed over 6 days – an extraordinary total of more than 384 lbs of food and drink:

Matthew’s case may have been one where treatment made things worse. Again, a physiological trigger is identified for his hunger – and not just adolescence, if that’s what those of you with teenagers at home are thinking! It was precipitated by a fever and vomiting, after which he was treated with ipecacuanha, an emetic, in the hope that after purging he would begin to feel better. However, his vomiting was made worse and this case sadly ended in death.

Many of the titles of these accounts, trimmed down from typical eighteenth-century descriptive verbosity, could read like clickbait headlines you might see today: for example, ‘Boy, 12, with canine appetite’, ‘Woman in Ross living without food or drink’, and ‘The Fat Man of Maldon’ (more on him in future, he’s worthy of his own article).

So why was the Royal Society interested in publishing these cases in a scientific journal? As far as I can tell, Royal Society Fellows were not obviously seeking to debunk the accounts received, though they did not hesitate to do so with other pseudo-sciences or impossibilities (perpetual motion springs to mind here). There’s no evidence of Fellows refuting ‘inedia’ in published responses in the Philosophical Transactions, and no discussion is noted in the meeting minutes.

If the Fellows were incredulous it remains unrecorded. I’d suggest that this is because they took it as a given that the cases of inedia at least were certainly fraudulent, even though each submitted account was at pains to demonstrate its veracity. Beyond that, the many accounts published in early issues of the Philosophical Transactions show above all a desire to collect information: about the unexplained, the extraordinary, and the extreme cases that might provide insight into the way things work by examining what happens when they behave differently. But perhaps they could have delved a little deeper?

(

( (

(