As the Royal Society’s 350th anniversary festivities draw to a close, we’re starting to plan ahead for a library-themed celebration of our own.

As the Royal Society’s 350th anniversary festivities draw to a close, we’re starting to plan ahead for a library-themed celebration of our own. On 8 May 1661 the Society’s Journal Book notes that ‘a motion was made for the erecting of a library’, and later in the same month ‘it was resolved that every member, who hath published or shall publish any work, give the Society one copy’, the first donations swiftly following from Sir Kenelm Digby and the ever-scrupulous Robert Boyle. We’re working on a series of exciting book-themed activities based around the Library’s 350th, and welcome your suggestions for anything you’d like to see happening in 2011.

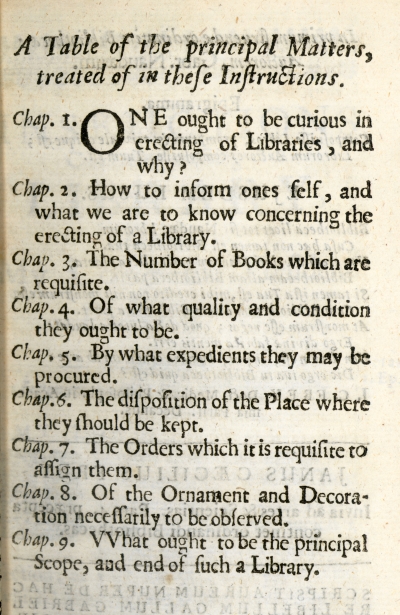

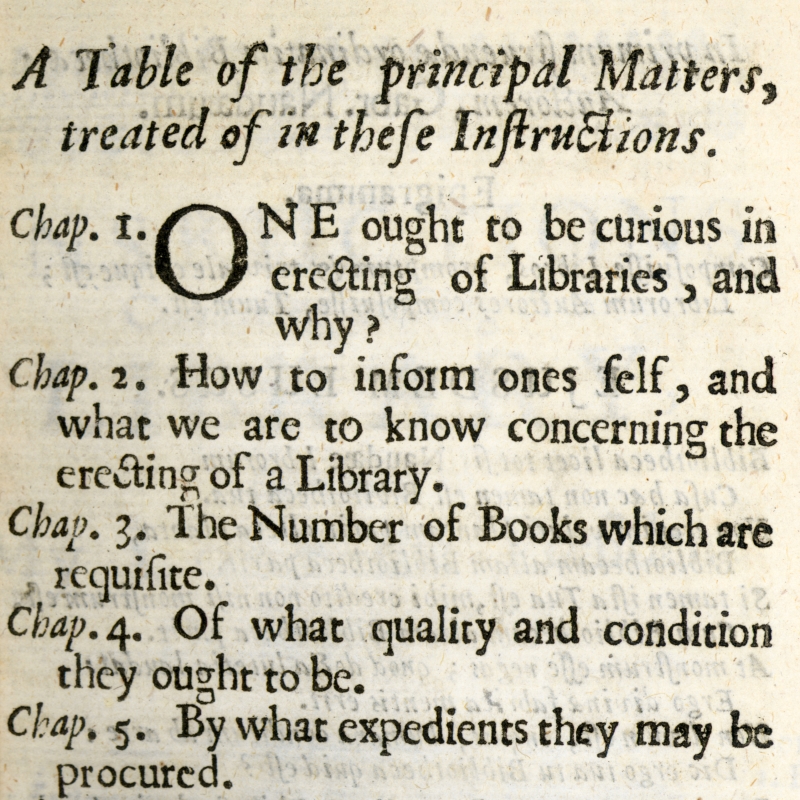

My delvings into the foundation of the Society’s Library have led me to a curious little book in our Early Works collection, Gabriel Naudé's ‘Instructions concerning erecting of a library’, in a 1661 English translation by John Evelyn. Originally published in France in 1627, the book is considered to be one of the founding works of librarianship, and some of Naudé’s recommendations are still capable of warming the hearts of a librarian in the modern digital age. In his introductory chapter, ‘One ought to be curious in erecting of Libraries, and why?’, he places a fine library at the peak of mankind’s accomplishments:

‘If it be possible in this world to attain any sovereign good, any perfect and accomplisht felicity, I believe that there were certainly none more desireable than the fruitful entertainment, and most agreeable divertisement which might be received from such a Library by a learned man’

In a rebuke to the virtuosi of the times who might only be interested in amassing the great works of the past, Naudé then sets out a collection policy which includes some highly topical science books:

‘Neither are you to omit all those which have innovated or chang’d any thing in the Sciences … Copernicus, Kepler, Galilaeus, [who] have quite altered Astronomie … There is nothing more apt to make a man a Pedant, and banish him from common sense, than to despise all Modern Authors, to court some few only of the Antient; as if they alone were, forsooth, the sole Guardians of the highest favours that the wit of man may hope for’

– sentiments very much in keeping with the progressive views of our founder Fellows.

Our archivists should be purring at Naudé’s suggestion that ‘it is the very Essence of a Library, to have a great number of Manuscripts’, and I’ve been chuckling over his advice on library ambience: ‘a free light, a good and agreeable prospect; the air pure, not near to marshes, sinks or dung-hills’. Our recently refurbished Archive and Rare Book storerooms have been upgraded to meet British Standard BS:5454, but I’m not sure this document includes a sub-paragraph on dung-hill proximity …

We diverge slightly from Naudé in his advice that libraries should provide for their readers ‘Carpets, Seats … Balls of Jasper … Pens, Paper, Ink, Penne-knifes, Sand, Almanacks … there is no excuse for such as neglect to make this provision’ – I’m afraid I’ve utterly failed to find Jasper Balls in our Library supply catalogues, and we much prefer pencil to pen, ink and sand these days. But his thoughts on book loans chime curiously with our own:

‘persons of merit and knowledge might be indulged to carry some few ordinary Books to their own Lodgings, nevertheless yet with these cautions, that it should not be for above a fortnight or three weeks at most’

Well, we’ve just set up a Modern Loan collection for our visiting readers (‘persons of merit and knowledge’ all); our loan period, proving that librarians down the ages think very much alike, is … three weeks!

Naudé’s book crops up again in Samuel Pepys’s diary, on 5 October 1665, where the (somewhat bemused) Pepys describes ‘reading a book of Mr. Evelyn’s translating and sending me as a present, about directions for gathering a Library; but the book is above my reach, but his epistle to my Lord Chancellor is a very fine piece.’ This Evelyn dedication, to the Lord High Chancellor Edward, Earl of Clarendon, comes across – as with many similar epistles from the 17th century – as extremely smarmy to modern-day eyes, but in among Evelyn’s flattery we find one significant phrase:

‘God has enlightn’d your great Mind, with a fervour so much becoming it, in the promoting and encouraging of the ROYAL SOCIETY’

– the ‘Colledge for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematicall, Experimental Learning’ founded at Gresham College on 28 November 1660 had hitherto been nameless, so we can thank John Evelyn, while introducing his translation of a most entertaining library manual, for putting the Royal Society’s name into print for the very first time.