Rupert Baker finds an eclectic range of subject matter in the Library's copies of The Gentleman's Magazine.

I recently, and coincidentally, had two run-ins with Peter the Wild Boy on the same day.

My first encounter with this celebrated 18th century feral child came while browsing through the newspaper racks in the Centre for History of Science. A fascinating Guardian article describes how analysis of a portrait of the young Peter, painted in the 1720s, has led to a new diagnosis of the chromosomal disorder Pitt-Hopkins Syndrome as the condition from which he suffered.

That same afternoon, I was showing some fellow Royal Society staff members around our Rare Book Room, and happened to pick a volume of The Gentleman’s Magazine from the shelves for their entertainment. Opening the journal at a random page, who should pop up but … Peter the Wild Boy again! A much older and tamer version this time – the 1782 account, by Lord Monboddo, sees Peter living quietly on a farm near Berkhamsted, aged around 70 and supported by a royal pension from King George III. His youthful dietary preferences – 'he then fed very much upon leaves, and particularly upon the leaves of cabbage, which he eat raw' – have broadened somewhat: 'At present he not only eats flesh, but has also got the taste of beer, and even of spirits, of which he inclines to drink more than he can get.'

The Gentleman’s Magazine, of which the Royal Society holds an almost complete run from its foundation in 1731 to the mid-nineteenth century, is full of such fascinating snippets. Despite a title which has been known to produce the occasional nudge and wink from people on my staff tours, it’s very far from being a Georgian lads’ mag; rather, its successive subtitles, ‘The monthly intelligencer’ and ‘Historical Chronicle’, hint at its usefulness for gentlemen of a certain social rank. Functioning partly as a digest of accounts from a proliferation of London newspapers, the introduction to the first volume of The Gentleman’s Magazine promises to preserve for posterity 'many things deserving Attention [which] are only seen by Accident, and others not sufficiently publish’d or preserved for universal benefit and Information'. The magazine also gave Samuel Johnson his first steady employment as a writer.

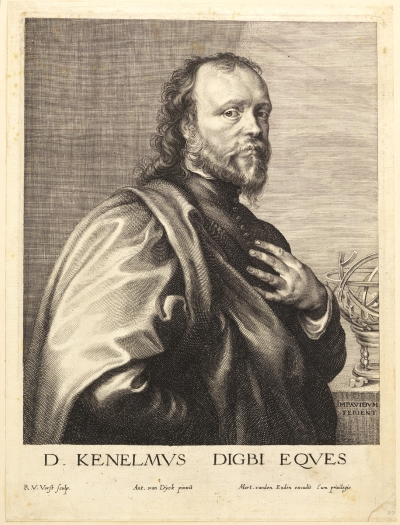

A look through volume 55, which contains Monboddo’s account of Peter the Wild Boy, gives a flavour of the magazine’s eclectic scope. Alongside fold-out plates of altar-pieces and Russian muskrats, we find ‘Intelligence from the East Indies’, summaries of parliamentary debates, tables of corn prices, and a sketch on the ‘Character of the late Capt. Cook, by a Naval Veteran’. Another of our Fellows pops up in a letter on ‘the most wonderful Cheshire Pig’ and other learned animals: 'Sir Kenelm Digby speaks of a baboon that played upon the guitar, and we are informed of an ape that played at chess in the presence of the king of Portugal'. Now, we’re big fans of Digby here in the Centre for History of Science, but his reporting of natural philosophical phenomena does occasionally leave something to be desired, as can also be seen by his part in the ‘powder of sympathy’ debate.

Sir Kenelm Digby, by Robert van Voerst (RS.17107)

The quirky nature of many articles in The Gentleman’s Magazine may have caused it to fall from favour with the increasingly professional Fellowship of the Royal Society. It’s probably no coincidence that our run of the journal ends in 1848, a year after major changes in the election rules of the Society, which began to shift the profile of our Fellowship from a majority of cultivated amateurs and patrons of science to a leaner body of leading scientists elected purely on scientific merit. Nonetheless, I’m glad our past librarians saw fit to retain the earlier volumes of the magazine. It provides a talking-point for tour groups, and can definitely be of use to Library readers looking for colourful background material for their eighteenth-century research projects – wild boys, muskrats, chess-playing apes and all.