Read more about a world of unconventional mutts who just happened to know some scientists (and vice versa).

Sometimes the history which catches my eye can accumulate around related topics and at the moment I’m having a run of doggie anecdotes. There are classic scientific studies by Royal Society Fellows in this area – probably we’ve all heard of the behavioural work of Konrad Lorenz or the conditioning of Pavlov’s dogs. But beyond the serious stuff there’s a world of unconventional mutts who just happened to know some scientists (and vice versa).

Portrait of John Hunter by Robert Home

I’ve always thought that the Society’s portrait of the surgeon John Hunter (1728-1793) is one of those pictures which are eye-catching for the wrong reasons. The very large dog resting its head on Hunter’s knee isn’t an obvious breed and seems badly painted, but that’s probably a disservice to the artist Robert Home. Hunter was well-known for experimenting with cross-breeding and there is a possibility that this may be one of Hunter’s wolf-dog hybrids. If so, the poor creature came to a sticky end, as many of Hunter’s dogs did, but in this case at the hands of a vigilante dangerous dog mob rather than by dissection.

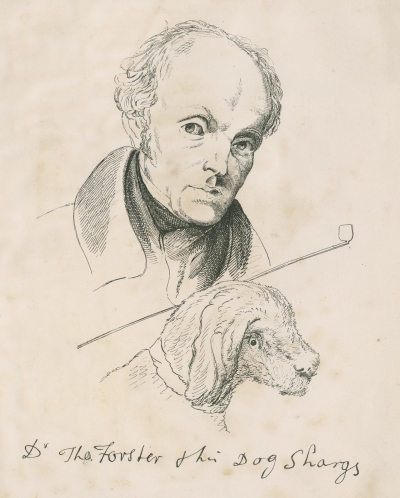

By contrast, the naturalist and occasional phrenologist Thomas Ignatius Maria Forster (1789-1860) took his love of pet dogs to opposite extremes. Forster never became a Fellow of the Royal Society, although he moved in Sir Joseph Banks’s circle and married Julia, the daughter of Henry Beaufoy FRS. He would later live and travel in Europe, usually with a pet dog in tow. His love of animals made Forster noteworthy as pioneering vegetarian and he likely influenced his acquaintance, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), in this regard. Forster wrote obituaries for many of his pets and described their virtues in rhyme. One portrait print in our collection shows Forster with the companion for whom he composed Inscription for the tomb of my old dog Shargs, commencing:

Beneath these trees I’ve buried my old dog,

Who, nine years by my side was wont to jog,

With him I loved the weary day to spend,

My brother mortal and my only friend.

But now his tongue is mute, his bones are old.

His nerves are quiet and his blood is cold.

It was, admittedly, a one-way exchange with Shelley.

Engraving of Thomas Forster, by Miss Turner

Charles Darwin thought deeply about selective breeding for particular traits in dogs, pigeons and other creatures in the course of his On the Origins of Species (1859) and in later works such as the Descent of Man (1871). Spouting verse wasn’t one of them, but his protégée John Lubbock (1834-1913) attempted to judge intelligence by basic communication with dogs. In his book On the senses, instincts and intelligence of animals…(1888) Lubbock related how his black poodle Van was trained to ‘read’ words on cards associated with particular objects. Cue correspondence from dog-lovers, eager to share with the longsuffering scientist details of how smart their pets were. “My little dog, a long-haired scotch Terrier has quite succeeded in learning to distinguish colours”, wrote one; “of course he sometimes is careless and makes mistakes.”

This was nothing compared to the talents of Duffer the counting dog, whose owner related that, in return for a biscuit, the untrained Dandie Dinmont would bark numbers up to ten on request. So far plausible? Well, Duffer could also subtract and multiply, “but he got tired and confused as the figures mounted up” (I sympathize). His owner “then told him a few simple historical facts upon which he might be able to answer numerically, such as How many wives had Henry VIII or How many King George’s were there? These he invariably answered correctly.”

Before I’m tempted to install Duffer as a posthumous honorary researcher in our history centre, there’s a nagging doubt about that biscuit reward and paying attention to visual cues. Dogs have been around people a long time, after all, and it’s not for our cultural conversation.