Discover how Thomas Hardy used the world of Victorian astronomy as a backdrop in 'Two on a Tower', the story of young stargazer Swithin St Cleeve and his dalliance with the aristocratic Lady Constantine.

You may be familiar with our 'Fellows in Fiction' loan collection in the Library, which focuses on books showing real Fellows of the Royal Society in imagined settings. My recent reading, however, has taken a slightly different line, with a fictional leading man trying to catch the Society’s eye and propel himself to scientific glory, only to be stymied by bad timing and an ill-starred romance. The name of our young astronomer hero is Swithin St Cleeve, and his creator is that great Victorian dealer in malign fate, Thomas Hardy.

Hardy’s Two on a Tower (1882) is light years from his finest work (The Return of the Native and Tess of the d'Urbervilles, if you ask me, though I’d also nominate The Woodlanders as a less widely known gem). However, it remains a fascinating read, and one in which Hardy interacts more closely with the Victorian scientific world than in his other works. And if you wanted to produce an illustrated edition, several pictures that we’ve recently digitised for the Royal Society’s Picture Library would serve very well.

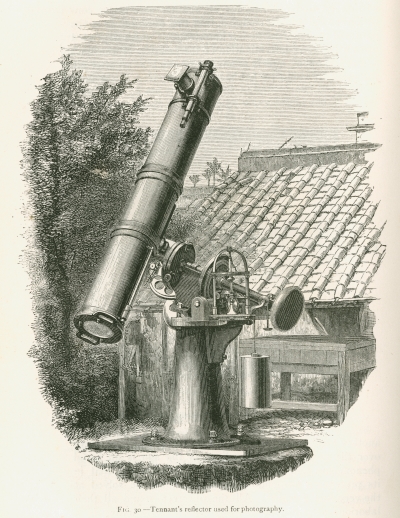

Two on a Tower begins with a landowner, Lady Constantine, finding Swithin observing the heavens from a tower on her estate. He is soon wowing her with his talk of the immensity of the universe and the insignificance of our place in the cosmos, though his small-talk is somewhat off-putting: "If you are cheerful, and wish to remain so, leave the study of astronomy alone. Of all the sciences, it alone deserves the character of the terrible.” Undeterred, and rather smitten with her young stargazer, Lady Constantine buys him a new equatorial telescope. Using this instrument, Swithin prepares his paper on ‘A New Astronomical Discovery’ (Hardy, unsurprisingly, is somewhat vague here, but it seems to be a theory on variable stars) and sends “One copy … to Greenwich, another to the Royal Society, another to a prominent astronomer”, only to discover that a rival has made the same discovery just a few weeks previously.

Rejection of his paper drives Swithin to despair, but he perks up when a new comet appears in the heavens. Claire Tomalin, in her excellent biography of Hardy, notes that the author observed such a celestial phenomenon (Tebbut’s Comet) in June 1881, a possible early inspiration for Two on a Tower; coincidentally, when the book appeared in volume form in October 1882 following initial serialization in the Atlantic Monthly, his readers would have been able to gaze at an even more prominent example, the Great Comet of 1882, as seen here in an image from our Picture Library:

Now, comets are well known as harbingers of doom, and it’s at about this point in the novel when Swithin takes his eyes away from his telescope for long enough to notice – and reciprocate – Lady Constantine’s attentions. All manner of shenanigans ensue, and the astronomy aspect of the story becomes rather lost in a tangled web of coincidence involving secret weddings, meddling brothers, amorous bishops, bequests from long-lost uncles and surprise news from darkest Africa, where Lady Constantine’s first husband met a terrible fate … or did he?

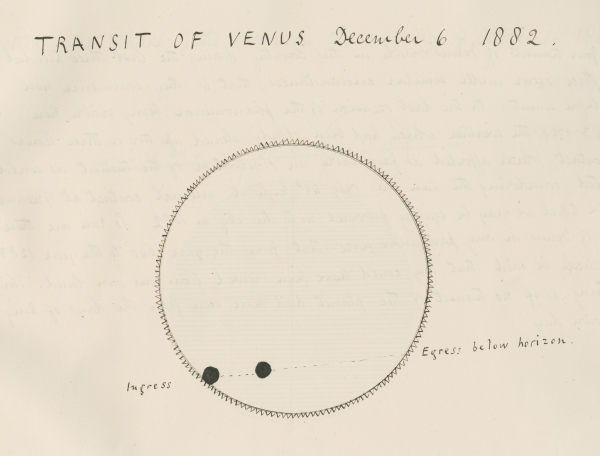

Frankly, it all gets a bit silly, but from our science-watching perspective there’s a revival of interest towards the end, when Swithin and Lady Constantine part and he heads off on an astronomy ‘world tour’. This takes him to Cape Town to see “those exceptional features in the southern skies which had been but partially treated by the younger Herschel”, the “gigantic refractor” at Harvard, and then “the Transit expedition, when he and his kind became lost to the eye of civilization behind the horizon of the Pacific Ocean”. Hardy avoids dates in his novel, but this ties in with the 1882 transit of Venus, the second of the pair which occurred in the Victorian era; we have a selection of images from both the 1874 and 1882 transits in the online Picture Library:

After a further sojourn at the Cape, Swithin returns home, as “The materials for his great treatise were collected, and it now only remained for him to arrange, digest, and publish them”. One wonders whether he managed to get his findings past the gatekeepers at the Royal Society this time around, as (minor plot spoiler) he survives past the final page of the novel – no mean feat for a Hardy leading man – and seems set for a notable career in observational astronomy. Swithin St Cleeve FRS? We shall never know…

I haven’t quite worked out a way of extending ‘Fellows in Fiction’ to include fictional Fellows – and there would be an awful lot of Patrick O’Brian naval yarns to purchase if I did – so you won’t find Two on a Tower on our Library shelves, though I’ll happily show you my personal copy. You will, however, find mention of Hardy’s novel in Richard Dunn’s useful The Telescope: a Short History on our ‘History of Instruments’ shelves, and our extensive collection of 19th century astronomy books includes many original images such as the one shown below – the type of telescope that Swithin St Cleeve might have used in between his dalliances with the dazzling Lady Constantine?