Keith Moore admires a lavishly-illustrated book of bird eggs and nests by the German engraver Adam Ludwig Wirsing.

The cartoonish notion of nicotine-scavenging sparrows is brought irresistibly to mind by a recent (very serious) Biology Letters paper ‘Incorporation of cigarette butts into nests reduces nest ectoparasite load in urban birds: new ingredients for an old recipe?’ by Monserrat Suárez-Rodríguez et al. The team from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México have written a fascinating insight into the use of dead cigarettes by enterprising avians as a means of keeping their nests pest-free. Do read it: apparently even man-made carcinogens have their uses.

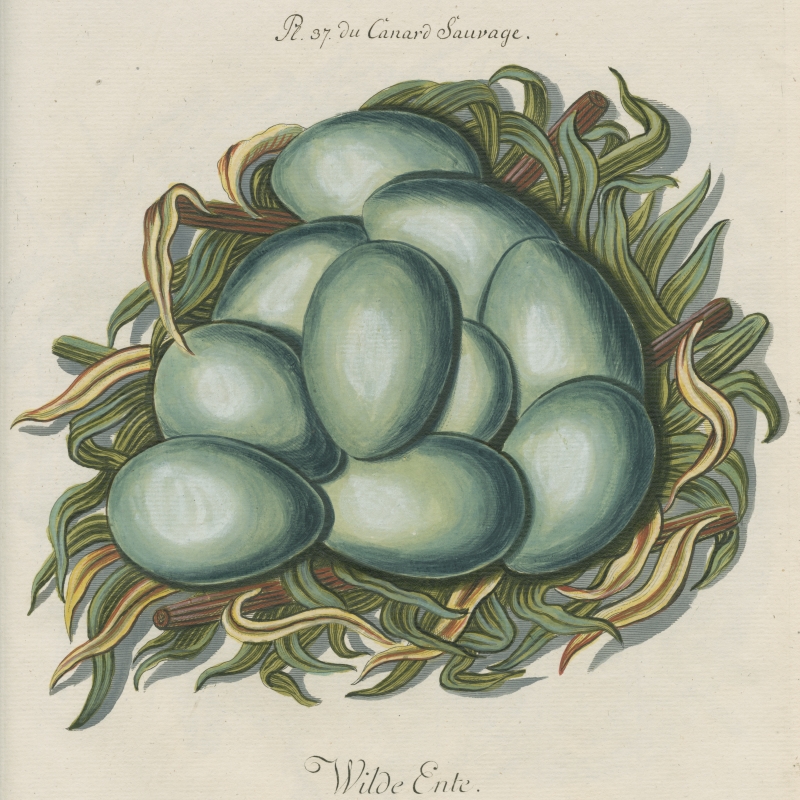

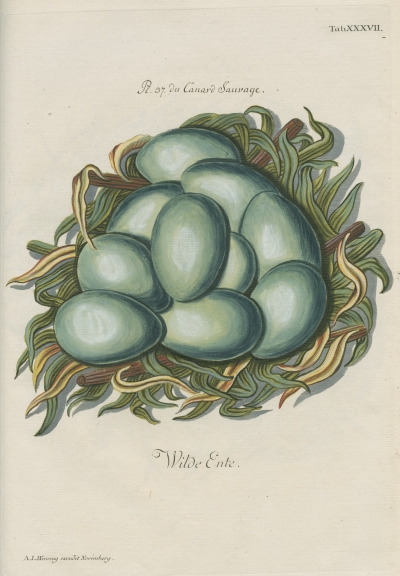

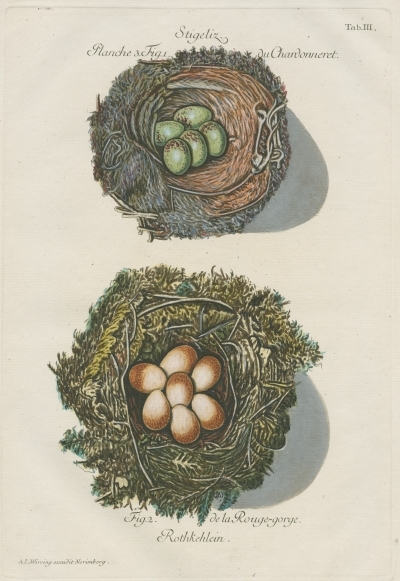

I suspect this won’t be the style of nest we’ll be seeing on our Easter cards this weekend, and perhaps you shouldn’t have it in mind as you’re breaking into a chocolate egg. Pristine beauty of the Fabergé kind is more likely. My own favorite nature studies of nests and their contents are to be found in the 1772 book Sammlung von Nestern und Eyern verschiedener Vogel by the German engraver and publisher Adam Ludwig Wirsing (1734-1797) with supporting descriptions by Friedrich Christian Gunther. Wirsing’s prints make the book: they are detailed and accurate in the scientific sense, but artistically quite sumptuous. The plates were printed on thick, hand-laid paper and were then vibrantly coloured to achieve a quite sculptural quality that would not have shamed the house of Fabergé. One can imagine reaching out and touching the blue duck-eggs of his ‘Canard Sauvage’.

Wirsing, A L and Gunther, F C Sammlung von Nestern und Eyern verschiedener Vogel (1772), plate 37 – eggs of the ‘Canard Sauvage’

Wirsing moved to Nüremberg to practice his art in 1760 at a time when the city was home to many fine natural history artists, including Barbara Regina Dietzsch (1706-1783). Like Dietzsch, Wirsing produced works on flowers in addition to his ornithological studies. He worked with the most prestigious of botanical painters, including someone very well known to the Royal Society: Georg Dionysius Ehret FRS (1708-1770), one of several fine artists ‘poached’ from the continent by Sir Joseph Banks.

The level of veracity found in the best of Wirsing’s egg paintings reminded me of another, far more famous work that might well feature on cards this Easter: Primroses and Bird’s Nest by the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), which can be seen at the Tate. In common with many English artists of the early-to-mid-nineteenth century, Holman Hunt greatly admired a scientific approach to observation and illustration familiar to the likes of Wirsing. Hunt’s teacher, John Varley (1778-1842) is said to have instilled in his charges the idea that they should “'go to Nature for everything'. Sound advice for both scientists and artists, even if the source is a little curious: Varley was an associate of William Blake and a believer in ghosts, visions and astrology, an odd figure to bridge the worlds of fine painting and natural history.

Wirsing, A L and Gunther, F C Sammlung von Nestern und Eyern verschiedener Vogel (1772), plate 3 – nests of the goldfinch and robin