What happened to photographs taken in the 1850s by Hugh Welch Diamond FRS? Keith Moore makes an unexpected discovery.

One of the subjects I’m interested in is the presence or absence of portraits in the Society’s collections. I’ve written recently on lost seventeenth century oil paintings for the Society’s journal Notes and Records but that’s the tip of the iceberg. There are many unexplained gaps in our picture holdings, most likely because illustrations were returned to authors, or never made it back from the engraver.

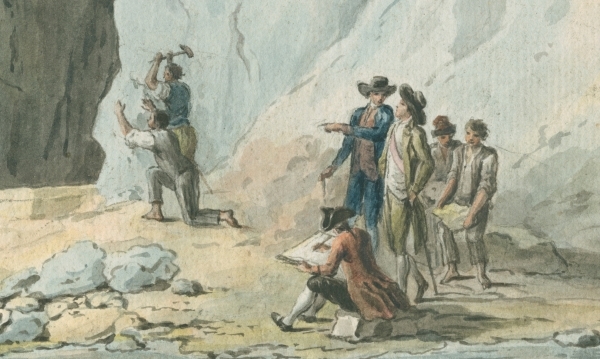

Sir William Hamilton’s party on the island of Ponza (detail), by Francesco Progenie, 1785. Royal Society L&P/VIII/186/4.

The fun bit of the job is finding (or more usually identifying) people hiding in scientific illustrations – a sort of highbrow Where’s Wally? For example, the Society doesn’t hold a formal portrait of the diplomat Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803), but take a look at the detail (above) from this watercolour in our archival papers by the Italian artist Francesco Progenie (fl.1770s-1780s). There’s Hamilton, clearly identifiable from his costume. I find images like this, of the great volcanologist doing what he loved best, infinitely more satisfying than a formal portrait. And of course the artist just couldn’t resist putting himself in the picture too.

One definitely missing and very famous set of images was attached to Hugh Welch Diamond’s manuscript paper On the application of photography to the physiognomic and mental phenomena of insanity. Diamond (1809-1886) acted as physician to the Surrey County Asylum at Wandsworth but was hugely influential as a leading photographer of the 1840s and 1850s. He helped to establish the Royal Photographic Society and aided Frederick Scott Archer (1813-1857) the inventor of the wet collodion process. Diamond’s only Royal Society paper was not printed in full. The Proceedings abstract concluded with the tantalising line that 'In the course of the paper frequent reference is made to the series of photographic portraits of lunatic patients with which it was accompanied.' No longer, I’m afraid.

Fortunately, surviving prints of Diamond’s patient photographs are pretty widely distributed. The proto-psychiatrist intended them to be used for diagnostic and identification purposes, but many are extraordinarily good portraits and as Diamond himself hoped “free altogether from the painful caricaturing which so disfigures almost all the published portraits of the insane…” I think that one or two rank as among the best images of Victorian women and completely transcend their original purpose: see this example in the New York Met.

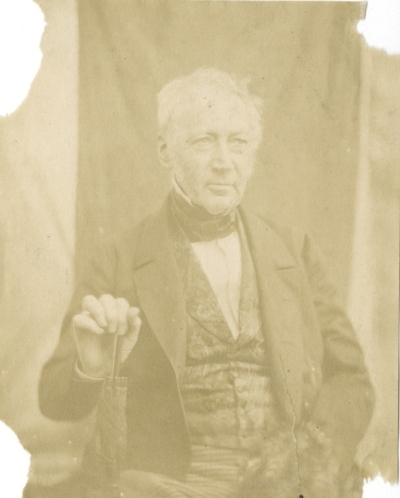

Photographic portrait of Andrew Ure, by Hugh Welch Diamond, 1853.

It was terrific therefore, to make a ‘find’ of Hugh Welch Diamond’s work in the Society’s collection. Cataloguing through carte-de-visite sized albumen prints of Fellows, I recognized an unaccredited image (above) of the Scottish chemist Andrew Ure (1778-1857) from a version in the Royal collections that had belonged to Prince Albert. The Royal Society’s print is a little worn around the edges and torn from an album, but definitely by Diamond. In checking a second photograph of Ure on a more robust mount, I was delighted to find the sitter’s age and costume (especially a tell-tale umbrella) appeared identical. A pair of early photographic gems in every sense.