Keith Moore dives into the curious world of the hydra, or polyp, and the research of Swiss naturalist Abraham Trembley FRS.

They have been the many-headed creatures of myth and the arch-enemies of those doughty Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. But real hydra, although they may not be much to look at, are far more interesting than either: immortality anyone?

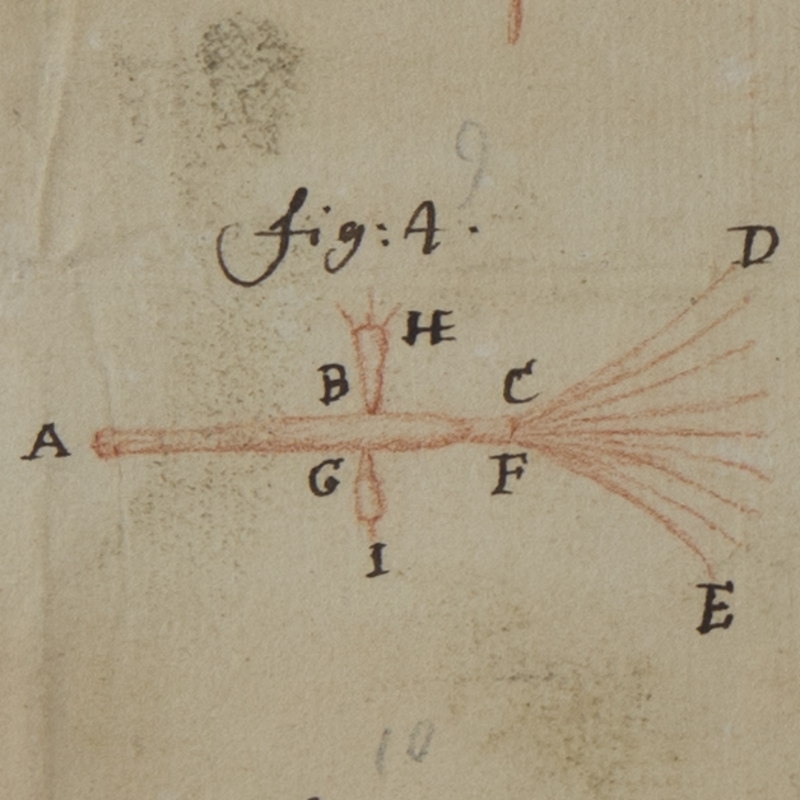

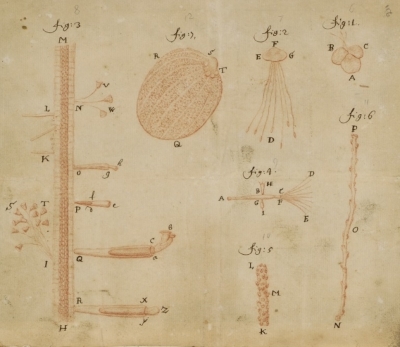

Microscopic views of duckweed and microorganisms, by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, 1702. The hydra is represented in figure 4.

Hydra were among the duck-pond detritus examined by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) in 1702 but seem to have been little noticed until they became the focus of researches by the Swiss naturalist Abraham Trembley (1710-1784). Trembley saw that what appeared to be a sessile frond-waving plant was actually locomotive and an active hunter. Curious – was this a plant or an animal? Trembley began to keep what he termed ‘polypes’ in freshwater jars and tanks, the better to explore their anatomy and to observe their behaviour.

Now if your name was Hercules and you cut off the head of a hydra, another one would grow. If your name was Abraham Trembley and you dissected a polyp, pretty much anything would grow back – not just the odd head or arm but another complete hydra if you cut it in two. Trembley found a means of turning the animals inside out and that didn’t bother them much either, since the outside would become the inside and vice versa. Such was the interest created among natural philosophers that Trembley became the centre of a network of exchange in which he sent hydra to scientists across Europe (a process described in Marc J Ratcliff’s excellent book The quest for the invisible) while the President of the Royal Society, Martin Folkes (1690-1754) repeated his regenerative labours before the Society’s Fellows.

Keeping polyps in tanks became a short-term fashion. Charles Lennox, the cricket-loving 2nd Duke of Richmond and Duke of Aubigny FRS (1701-1750) visited Trembley’s laboratory in Sorghvliet (now the residence of the Dutch head of state) and was later kept entertained in his own home by hydra, housed in a sort of townhouse miniature equivalent of the wild animal menagerie he maintained at his country estate at Goodwood. Richmond House in London must have been an extraordinary place. It is perhaps best-known for providing the backdrop to the huge firework display that launched Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks (1749). Just as that exhibit was terminated by a runaway fire, so the Duke would lament that his hydra were killed off, Icarus-like, when their watery home was left too close to a sunny window-ledge.

For research scientists today, Trembley’s little beasts are not simply a footnote in history. There is some evidence to suggest that hydra possess biological immortality – failing an accident or carelessness like the Duke of Richmond’s, they can reproduce by budding and don’t exhibit obvious senescence (ageing to death). This has intrigued some scientific groups although in reading summaries of the research, it seems amusingly apparent that nobody’s quite sure how long individual hydra can keep going. You’d have to watch them an awfully long time and well, life’s too short.

But it isn’t just cell biologists who have the hydra bug; the pond-life Methuselah has been promoted as a handy classroom teaching tool for budding biologists too.

Abraham Trembley in his laboratory with pupils, by Jacobus van der Schley. From Trembley’s Memoires pour server a l’histoire d’un genre de polypes d’eau douce (Leiden, 1744)

Abraham Trembley would have been delighted, since he was professionally engaged in the more traditional form of human legacy, as tutor to the children of his patron Count Willem Bentinck (1704-1774). Rather charmingly the boys feature in each of the engravings from his book Memoires pour server a l’histoire d’un genre de polypes (1744) showing Trembley at work They are doing what children everywhere do best: trawling ponds with nets and watching their catches in aquaria. All of which provides a continuing immortality, for the Swiss scientist at least.

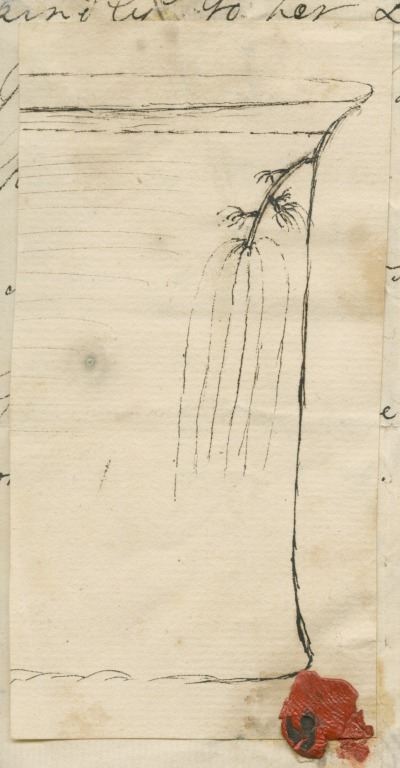

Freshwater hydra in a glass jar, by Charles John Bentinck, 1741. Charles Bentinck (1708-1779) was the younger brother of Willem Bentinck, 1st Count Bentinck.