Keith Moore highlights the work of entomologist Eleanor Ormerod and conchologist Vera Fretter, including some intriguing literary connections.

Few important scientists get the full-blown literary treatment from a major writer of English. I think we can cheerfully ignore George Bernard Shaw’s version of Isaac Newton (In Good King Charles’s Golden Days, 1939). But one intriguing match-up is the essay Miss Ormerod (1923) by the novelist Virginia Woolf, an interpretation of the life of the Victorian entomologist (and notorious sparrow-nemesis) Eleanor Anne Ormerod (1828-1901).

Like many nineteenth-century women scientists, Ormerod had family connections to the Royal Society. Her father, the historian George Ormerod (1785-1873) was a Fellow and her brothers went into various branches of science. But Eleanor carved out a quite unique role for herself – by force of circumstance, since conventional scientific careers were not for women then – as an economic entomologist. She was interested in insects that harmed the livelihoods of gardeners, farmers and fruit-growers and this eventually made her something of a national figure, widely-read and an authority consulted by the Royal Agricultural Society (unpaid, naturally). It was once Ormerod’s life was fully independent of parental influences that her career flourished, something Woolf must have found highly appealing.

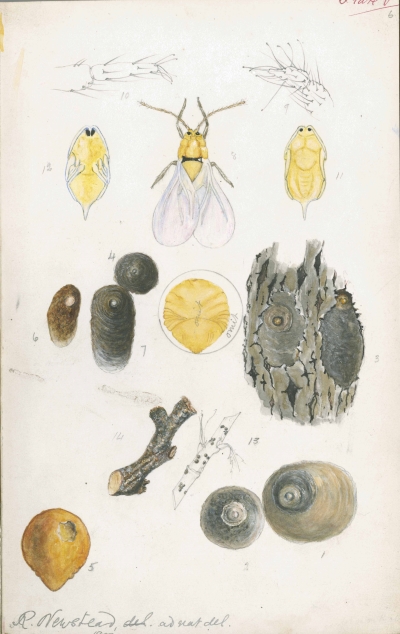

Ormerod’s agriculture was deeply unsentimental: the chemical carpet-bombing of garden pests using Paris Green (copper acetoarsenite) and bounties on the grain-eating house sparrow are among the best-known examples. But in a neat reversal of norms Eleanor had a hand in guiding a male scientist and one who became very well known to the Royal Society. Robert Newstead (1859-1947) started to correspond with her while a relatively lowly curator of the Grosvenor Museum in Chester. The most important of Newstead’s manuscripts in the Society’s collections, his British coccidae (1901-04), bears the hallmarks of Ormerod’s influence. The very fine illustrations show not just the insects, but also the agricultural damage they do. The author became an FRS and an eminent Professor of Tropical Diseases at Liverpool University specializing in human disease carriers such as the tsetse-fly.

European fruit scale by Robert Newstead, c.1902 (Royal Society MS/53/1/1/6)

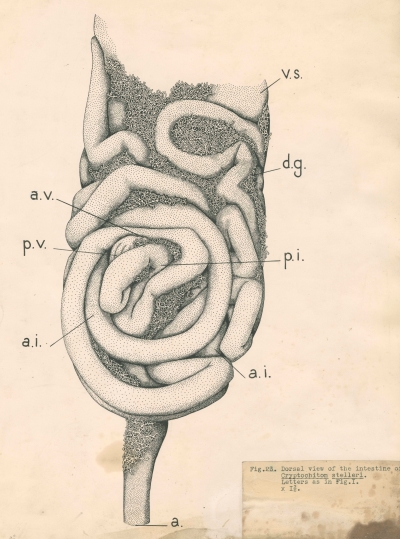

Natural history often throws up illustrious pairings of this kind. I’ve just been cataloguing some twentieth-century drawings from the natural history classic British prosobranch molluscs prepared by Vera Fretter (1905-1992) and Alastair Graham FRS. Both were highly talented artists and in this particular collection there are some very rare survivors of Fretter’s ink drawings of around 1936-1939. Their salvaged, slightly damaged appearance is the result of both Fretter’s house and university (then Royal Holloway) being bombed out during the Second World War.

Intestine of Cryptochiton stelleri (Gumboot chiton) by Vera Fretter, c.1939 (Royal Society MS/875/1/3)

No literary tie-ins there, you might think: but well, just maybe. We know that the specimen shown here is the Pacific marine mollusc Cryptochiton stelleri and Fretter obtained it from California via the Turtox General Biological Supply House in Chicago. The most famous Monterey-based collector was Ed Ricketts (1897-1948) or ‘Doc’ as he was fictionalized by John Steinbeck in Cannery Row (1945). Now we’ll never know if Fretter, Ricketts and Steinbeck touched hands via mollusc, but do read the book – you won’t find more evocative writing about seashore collecting. And if you’d like to take it just a little further (I won’t) you can read Ricketts’ own account of attempting to tuck into the aptly-named Gumboot chiton in Between Pacific tides (1939). The same beast and the same publication year as Fretter’s technical description.

Will you be wanting chips with that, Mr Steinbeck?