Keith Moore discovers fairy lights and a ghostly apparition in the collections of the Royal Society.

Christmas, and what could be better at this time of year than tales of light and darkness?

If you’ve decorated your Christmas tree, you may not realise that you have to thank a Royal Society scientist (of course) for one festive tradition. The original fairy-lights were the brainchild of that bright spark who really invented the light-bulb, pioneering electrician Sir Joseph Swan FRS (1828-1914) – do feel free to hiss at my special panto villain, Thomas Edison.

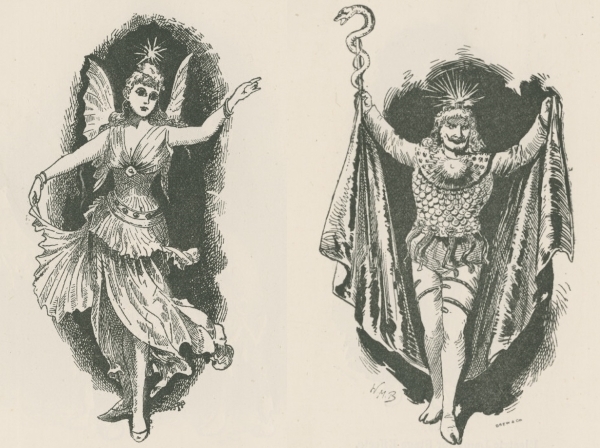

Of course you may think I’m biased in favour of a fellow North-Easterner, but Swan’s talents were certainly recognised by the theatre impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte (1844-1901). D’Oyly Carte wanted magical effects for the staging of the ‘fairy-opera’ Iolanthe in 1882 and he turned to Swan to provide the tiny electric star lights that his fey-folk wore in their hair and wands, powered by miniature battery packs. Producers quickly recognised the potential for this new special effect and it wasn’t long before stage demons carried scary red lights to illuminate their wicked deeds.

Two performers at the Crystal Palace in 1892: (L) a dancer from the ballet Little Red Riding Hood, featuring a head-star illuminated by an electric light (R) the ‘Demon King’ from the pantomime The Forty Thieves, with a head-dress and breast-piece lit by ruby electric lights. Composite of figures 63 and 60 from the book Portative electricity by J T Niblett (London, 1893).

But theatrical devilment isn’t really terrifying. For that you need a traditional ghost story by moonlight and candle-gutter. Happily, many eighteenth-century Royal Society Fellows were also antiquaries and I was delighted to find a ghostly tale from the Norfolk coast in our scientific archives quite recently: a warning to the curious, if you will.

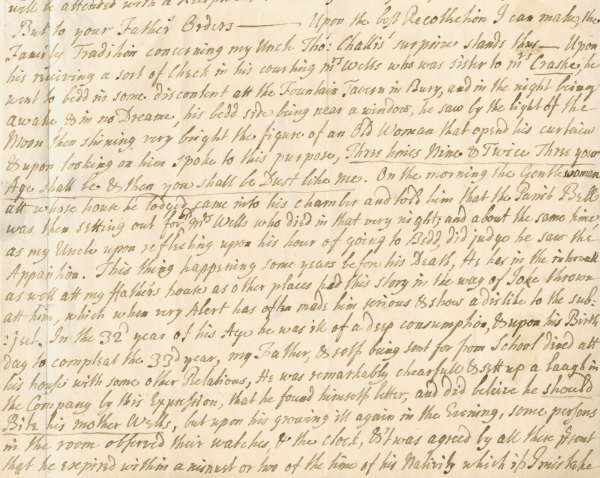

This manuscript (a letter composed on Christmas Eve) centres on a family tradition of the Society’s President Martin Folkes (1690-1754). A traveller sleeping at an inn is woken by a shrouded woman, who predicts the hour of his death: “Three times Nine & Twice Three your Age shall be & then you shall be Dust like me”. The next morning our traveller is informed that the parish bell tolled at that precise moment to signify the passing of the unhappy woman. Naturally the augury gradually preys on his mind until the appointed hour of his thirty-third birthday when in the midst of a party he expires, fulfilling the weird woman’s prophecy to the minute.

Detail of the ghost story in Royal Society MS/790/23/1.

And it is that last detail which makes the story fascinating. On the surface it is a tale of the uncanny: but beneath that is a text about the ability to measure time. The manuscript dates from 1735 and it describes events supposed to have taken place in the narrator’s childhood, perhaps at the turn of the eighteenth century. Our first measure of time is the parish bell tolling in the fashion of Shakespearean chimes at midnight. But years later, the traveller’s death is in a private house: here, the gentlemen present check their pocket-watches and a house-clock “& ‘twas agreed by all these present that he expired within a minuet or two of the time of his Nativity which if I mistake not was between the Hour of Eleven & Twelve”.

The story only works because of the availability of accurate timepieces – particularly the types of personal watches then being manufactured by the likes of Thomas Tompion (1639-1713) and George Graham FRS (1673-1751). Which leads neatly to the question – when did the country-house clock striking midnight become a signifier for a ghostly presence? The idea of a temporally-imprisoned spirit is as old as Hamlet’s father, but the seemingly old-fashioned trope of the chiming clock can only have been around for as long as accurate long-cased clocks became relatively common; and therefore familiar.

So, if we think that a Christmas tale of technological terror featuring the internet or social media is a new idea, perhaps we should all think again. That ticking watch, quietly swinging pendulum and the count of the midnight bell may be as much a part of the season as fairy-lights and a genuine ghost of Christmas science past.

A happy Christmas everyone, from all at the Royal Society Library.