Authors of a paper published in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface investigate the biomechanics of popcorn.

There’s more to this humble cinema snack than you might think…

Published today in Journal of the Royal Society Interface, the authors of this paper investigate the biomechanics of popcorn. They explain how a piece of popcorn bursts open, jumps and emits a pop sound within a few hundredths of a second, and all popcorn, no matter what shape and size, pops at the same temperature jumping a few millimetres to several centimetres high, with the popping noise due to the release of water vapour.

Emmanuel Virot and Alexandre Ponomarenko, who carried out the study, describe how popcorn became their experiment:

‘Initially, we were working on the wind speed required to break trees during storms. At the same time, our colleagues of the Laboratory of Hydrodynamics of École Polytechnique were interested by fast physical phenomenon, like drop impacts or explosions at the surface of water. To observe these phenomena they were using high-speed cameras recording more than 10,000 images per second. We took advantage of this technique to study plants and then started to observe popcorn explosions, and it turned out that this phenomenon covered several scientific fields: biophysics, thermodynamics, biomechanics and acoustics’.

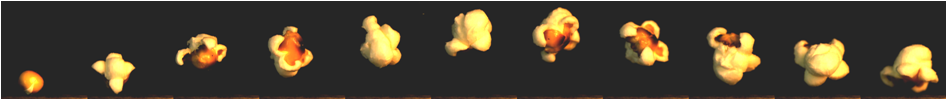

Popcorn is the movie: video shows jump of a piece of popcorn with a leg of starch, recorded at 2900 frames per second

Scoffing popcorn takes no time at all, but studying it takes dedication. Approximately 400 pieces of popcorn were used to record the jump movies. These were heated one by one, with each movie taking 5 minutes to make and a further 10 minutes to analyse. Did this give the authors an appetite for their experiment? Not quite, but Alexandre recalls ‘the smell of popcorn spread into other experimental rooms attracting colleagues to come and comment on what we were doing, some of whom ended up in the coffee room eating our experiment’.

According to the authors, there are at least three reasons to study popcorn. Firstly, a piece of popcorn has a singular way of jumping which is midway between two categories of moving systems: explosive plants using fracture mechanisms and muscle-based animals. This unique characteristic gives popcorn a unifying role in biomechanics. Secondly, popcorn is particularly well adapted for teaching. It’s the perfect example of an everyday object covering many concepts of physics which can easily be approached in a classroom with a simple experimental set-up. And finally, working at the frontiers of classical scientific fields helps to find analogies in physics that are useful to describe natural phenomena and their laws.

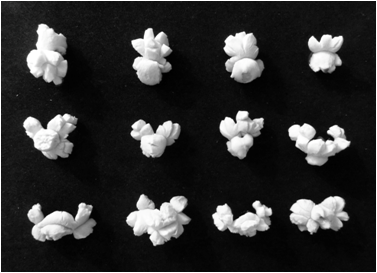

A piece of popcorn jumping in approximately 100ms (A. Ponomarenko and E. Virot)

Asking the authors the best way to prepare popcorn at home, they said ‘traditionally this is done with a pan and some oil. However, it appears easier to set an oven at a fixed temperature of 180 degrees Celsius and wait a few minutes, and we justify this in our article; we discuss why this critical temperature hardly depends on kernel characteristics’. Baked popcorn is the way forward.