In our first of this series, Sunetra Gupta, Professor of Theoretical Epidemiology at the University of Oxford and member of the Editorial Board of Phil Trans B, tells us about an inspirational woman, Mary Somerville.

To celebrate 350 years of scientific publishing, we are inviting our readers to tell us about their favourite papers from the Royal Society archive. In our first of this series, Sunetra Gupta, Professor of Theoretical Epidemiology at the University of Oxford and member of the Editorial Board of Phil Trans B, tells us about an inspirational woman, Mary Somerville.

For eight years Mary Somerville had as her companion a mountain sparrow which perched, and even slept sometimes, on her sleeve as she wrote her last book: “On Molecular and Microscopic Science”. She records in her memoirs how distraught she was when the poor bird was found, one morning, drowned in a jug of water. She was by then in her eighties and living in Italy; they had moved there in 1840 on account of her husband William’s ill health and for 20 years led an extraordinarily peripatatic existence (by the standards of our times, admittedly) – summer in Genoa, winter in Rome, spring in Venice; she had chosen to remain, and settle in Naples, after he died.

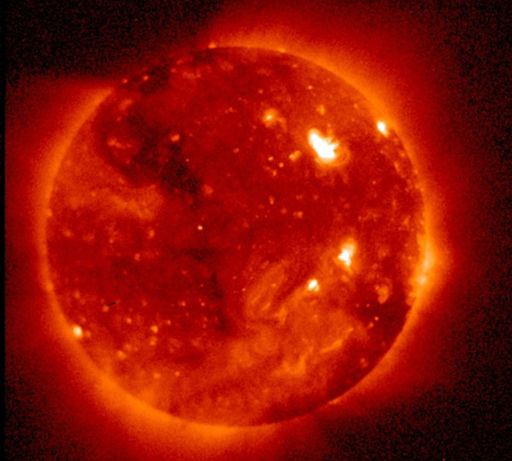

It was William who communicated “On the Magnetizing Power of the More Refrangible Solar Rays” to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, since she – as a woman – was not permitted to do so herself. The opening sentence

“In the year 1813, Professor MORICHINI of Rome discovered that steel, exposed to the violet rays of the solar spectrum, becomes magnetic”

has all the intensity and oblique beauty as the first lines of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude”: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendia was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice”. What follows, however, in Somerville’s paper is the quiet and resolute performance of a set of scientific tasks to establish the truth of this conjecture. The prose is of astonishing clarity and yet dances with contained excitement. Sewing needles, ribbons of various colours, and wax enter liberally into the list of ingredients but, rather than creating an impression of cute feminine resourcefulness, these objects speak of Somerville’s creativity and determination. We know now that the union between light and magnetism does not manifest in quite so simple a way, but it is wonderful to read of how it was anticipated by the thinkers of the early 19th century. As Somerville later expresses it herself in her extremely popular book “On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences”: “an occult connexion between all these agents, which probably will one day be revealed. In the mean time it opens a noble field of experimental research to philosophers of the present, perhaps of future ages.”

The degree to which experiment and theory complement each other, and that they may nonetheless be ‘performed’ by separate individuals is a clear message to take away from Somerville’s writings. In her memoirs, she says:

“Many people evidently think the science of astronomy consists entirely in observing the stars, for I have frequently been asked if I passed my nights looking through a telescope, and I have astonished my enquirers by saying I did not even possess one”.

Mere observation is never enough, and neither is mere speculation. These are all good lessons to take from Mary Somerville’s writings but what her papers and personal recollections also contain for me are object lessons on how to live and think. I wander into my kitchen to cook supper and put on a Steve Harley song:

“Light shone with a breath-taking energy

Boats bobbin’ on the waterline

Dusk settled but the flies didn’t bother me

I was high on the Coast of Amalfi.”

It reminds me of Mary Somerville – how wonderful is that?