This post relates to our Future of Scholarly Scientific Communication events (#FSSC), bringing together stakeholders in a series of discussions on evolving and controversial areas in scholarly communication, looking at the impact of technology, the culture of science and how scientists might communicate in the future.

We have all experienced that moment of epiphany when the very act of explaining a tricky concept to a friend or relative helps simplify a complicated problem, even understand it more deeply. So why not ensure that every scientific paper carries a lay summary?

The many benefits of doing this were outlined recently by Lauren Kuehne and Julian Olden of the University of Washington, Seattle. They concede that some scientists will moan that this as just one more hurdle in peer-reviewed publishing. But it would do a power of good for the visibility, impact and transparency of science if everyone adopted clear, simple and brief summary statements about the why and ‘so what?’ of research.

I also dream of the day when papers no longer contain circuitous, impenetrable sentences, when researchers no longer reach for clunky words such as ‘facilitate’, or write in the passive voice, as if some mighty and impersonal force had done their research. Scientific papers are often so opaque and jargon-laden that science is not really open at all, despite all the lip service paid to the idea of ‘open science.’

But when I mulled this over at a Royal Society meeting on the Future of Scholarly Scientific Communication (which resumes next week), I realised that within that little word ‘lay’ lies a subtle issue that is often overlooked.

To appreciate the true value of lay summaries we have to unpack what we mean by ‘scholars’ and the ‘layperson’.

A genomics researcher can find it just as hard as a smart-but-scientifically-ignorant lay person to read a particle physics paper, let alone the outpourings of a pure mathematician. Relative to the author of a scientific paper, specialists from other fields blend into that familiar-yet-mysterious blob we call ‘the public’.

In reality, ‘the public’ is a mishmash of many different audiences. Communicating with kids requires a different approach from that used for science graduates, for example. The latter can be lumped together with most scientists too – most scientists approximate to members of the ‘lay’ audience. Only a handful count as scholars, those who belong to the same scientific tribe as the author of a research paper.

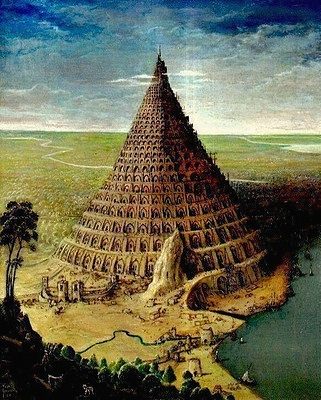

As a corollary, ‘lay’ summaries will not only strengthen connections between science and the public, and help justify how researchers spend taxpayers’ money, but, importantly, network different kinds of scientist as well. (Indeed, it would be interesting to find out whether science’s Tower of Babel is one reason that interdisciplinary research has not advanced as quickly as some expected.)

Ultimately, the scientific enterprise needs capsule summaries that not only help inspire bureaucrats, policymakers, the media and so on, but also fire up scientists from other fields. In this way, ‘lay’ summaries will help build bridges between the many ivory towers of research, providing a spur for big, interdisciplinary science.