Keith Moore takes a close look at the work of extraordinary microscope artists, from Robert Hooke to Philip Henry Gosse and John Denis Macdonald.

I was fortunate enough to have an invitation to speak about Robert Hooke’s Micrographia at the Natural History Museum recently, which got me thinking about small things. I couldn’t let this anniversary year go by without writing a little about Hooke and his scientific successors with the microscope. Newton may have stood on the shoulders of giants, but Hooke can fairly lay claim to having danced on the head of a pin.

Alas it’s the tip of a 350-year old pin that gets reproduced in Micrographia (1665) with all its manufactured imperfections. But in one of my favourite sections of Hooke’s work – his description of the difficulties of depth perception using an optical instrument – more beautiful fixings make an appearance:

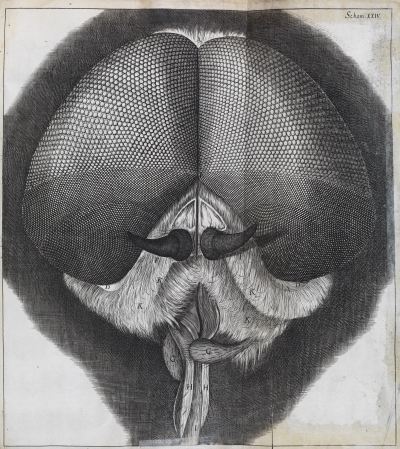

Microscopic view of the head of a grey drone-fly, by Robert Hooke. Schem. XXIV from Micrographia: or some physiological descriptions of minute bodies made by magnifying glasses, 1665

‘The Eyes of a Fly in one kind of light appear almost like a Lattice, drill’d through with abundance of small holes … In the Sunshine they look like a Surface cover’d with golden Nails; in another posture, like a Surface cover’d with Pyramids; in another with Cones…’

Despite the many fine seventeenth century witnesses to magnified natural history – Nehemiah Grew, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and Marcello Malpighi among others – I’m more entranced by their lesser-known nineteenth century equivalents. The Kew-based Franz Bauer (1758-1840) is a long-time favourite, but I’ve been sourcing images of two more extraordinary microscope artists for the Society’s picture database: the aquarium pioneer Philip Henry Gosse (1810-1888) and the naval officer John Denis Macdonald (1826-1908).

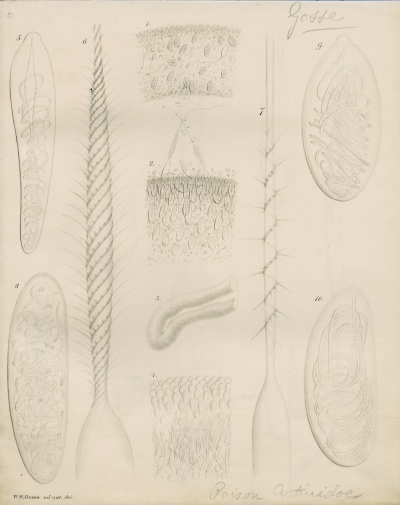

Stinging structures of sea-anemones, by Philip Henry Gosse, 1857. Unpublished illustrations from the manuscript version (AP/40/14) of the paper ‘Researches on the poison apparatus of the Actiniadae’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, vol.9 (1857-1859), pp.125-128.

Both were fascinated by the tiniest of marine organisms. Gosse is famous for his beautifully illustrated mid-Victorian books and anyone who has ever taken children to a sea-life display owes him a debt: his ‘Fish House’ (at London Zoo) was the first marine display of its type for the public. Gosse’s scientific illustrations are shown more rarely than the popular chromolithographs and I can understand why. The artist’s pencil-work (seen here in the needle-like stings of sea anemones) is highly refined and ideal for capturing the most translucent of structures; but it's difficult to reproduce well.

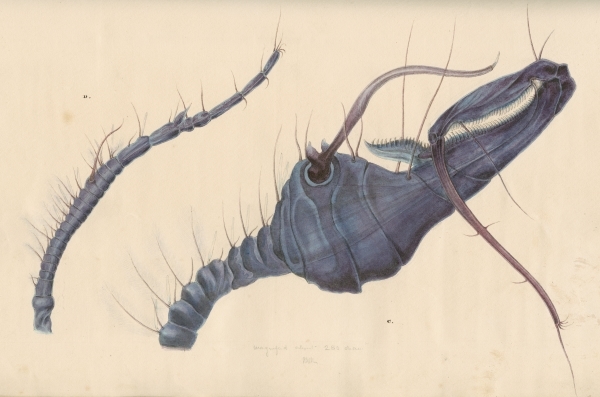

Crustacean antennae under magnification, by John Denis Macdonald, 1853. Illustration from the manuscript version (AP/34/16) of the paper ‘Observations on the anatomy of the antennae in a small species of crustacean’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, vol.6 (1850-1854), pp.295-296.

By contrast, Macdonald’s microscope artwork is bolder and often colourful: why is he not better appreciated? Many of the Royal Society’s illustrations from his pen and brush were made during the surveying cruise of HMS Herald round Australia and Fiji during the mid-1850s. Macdonald was the assistant-surgeon and marine naturalist, continuing the work of the future Royal Society President, Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895), who carried out the similar duties aboard the predecessor vessel HMS Rattlesnake. Unfortunately for Macdonald, the contents of his Pacific papers were mostly abstracted in the Society’s Proceedings, only a few appearing in the more expansive Transactions. That meant no plate illustrations – his watercolours, therefore, languished.

Both Gosse and Macdonald had an endearingly dotty side: Gosse managed to shuttle between an impressive cast of protestant groups (Moravians, Plymouth Brethren, whatever was locally to hand) before coming up with the book Omphalos (1857) which attempted to explain deep time by maintaining that the by-then irrefutable geological evidence had been divinely ‘planted’. By 1893 Macdonald was promoting his scheme for linking colour to musical harmonies. Don’t ask – just enjoy their very real talents for scientific art of the best kind.