Keith Moore takes a look at Joseph Goold and his twin elliptic pendulum harmonograph.

You probably won’t be surprised to read that among my vices is a serious second-hand bookshop habit; another is a little rummaging around antique and flea-markets. These are all good places to pick up pieces of science ephemera and I thought I’d share my latest bargain.

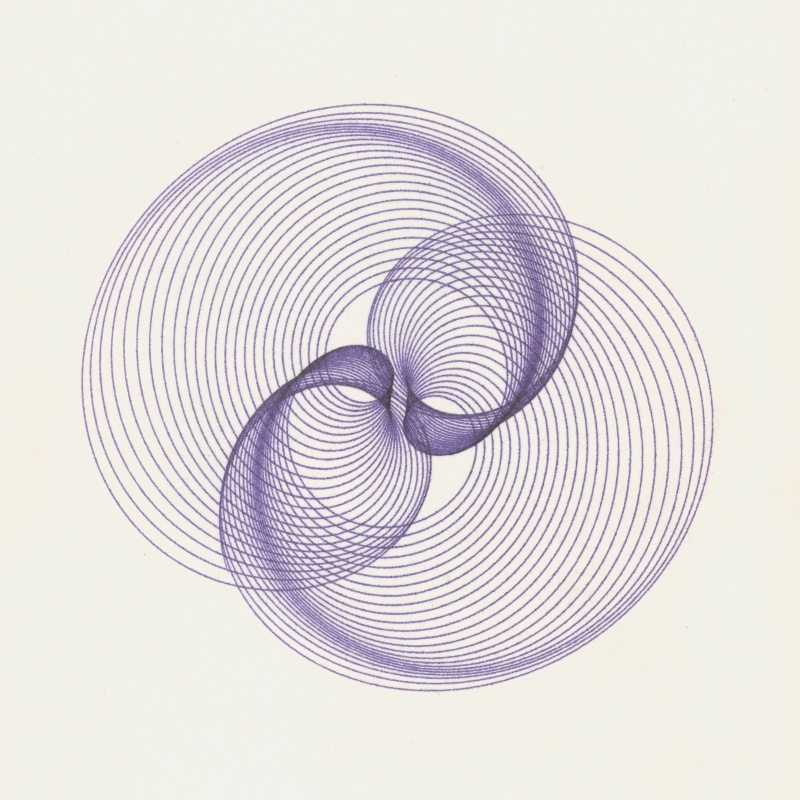

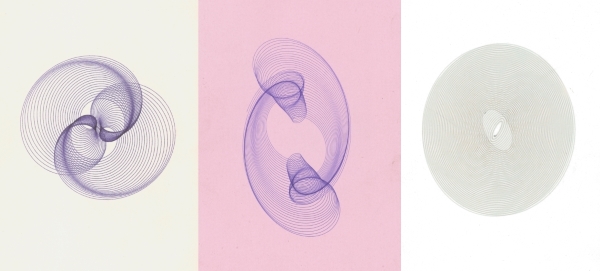

MM/22/84, MM/22/86 and MM/22/85

Curators have an eye for the semi-obscure and I recognised these little drawings straightaway. The swirling geometric patterns are variations of Lissajous curves created by a harmonograph, one of the many short-lived Victorian and Edwardian hobby-crazes based upon simple scientific principles. I rather like this one – the notion of art being created by entirely mechanical means while the artist puts the kettle on is quite appealing and the idea get resurrected from time to time by contemporary artists, recently by Anita Chowdry.

There is a considerable history of artists and scientists producing ‘automatic’ art by the intervention of technology. The nicest example is the use of the camera lucida from the early nineteenth century. This prism-based artist’s tool was patented by a Royal Society President, William Hyde Wollaston (1766-1828) and it allowed the user to see a landscape as if projected onto drawing paper. Several scientists, including Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) were very adept at capturing perspective in this way and Herschel took his camera lucida on honeymoon, to sketch views in South Africa. His friend William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) failed miserably to draw scenery at Lake Como during his nuptials in 1833, setting him on the road to contriving the completely mechanical photogenic drawing process announced in 1839 – photography, as we know it now.

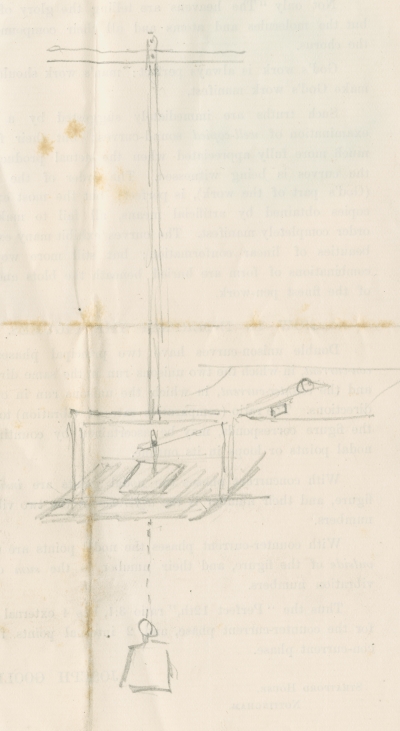

A little sketch (above) on the back of a pamphlet found with my drawings, Sound curve tracings, shows the particular instrument which made them: a twin elliptic pendulum harmonograph invented by Joseph Goold of Nottingham. Goold contributed to a book on the subject Harmonic vibration and vibration figures in 1909. The principle is quite simple – a pendulum guides a pen across paper, which is itself mounted on a moving support controlled by a second pendulum. The combined effect can produce highly complex and beautiful patterns.

Naturally, you can build a harmonograph yourself since there are plenty of how-to instructions available on the internet. You probably won’t want to go to the lengths of Ivan Moscovich (b.1926) who patented the computer-controlled ‘Moscovich Harmonograph’ shown at the ICA in 1969: but you should look at the results, which are quite stunning.