Why was Royal Society President Sir Joseph Banks on the receiving end of stinging criticism in 1802, and who was 'Misogallus'? Rupert Baker investigates.

These days, Presidents of the Royal Society serve a five-year term in office, and you may have seen the recent announcement of our President Elect, who will take up the post on 1 December this year.

Until the latter years of the nineteenth century, however, terms of office varied widely. Following Viscount Brouncker’s 15-year stint as our first President (1662-1677), there were several one-year spells by high-ranking (but not very scientific) figures such as Sir John Hoskyns, Sir Cyril Wyche and Thomas Herbert, 8th Earl of Pembroke. The death of an incumbent occasionally gave rise to a short, interim presidency until a formal election at the next Anniversary Meeting – James Burrow is notable for being roped in twice, serving for just over a month in 1768 following the death of James, Earl of Morton, and for a further five months in 1772 to complete the term of the late James West (there’s nothing in the statutes of the time indicating that the name ‘James’ was de rigeur for a President, but it certainly appears to have been popular).

At the other end of the scale, Sir Isaac Newton is runner-up with over 23 years in the presidential chair, but the gentleman who held the post for the longest term is Sir Joseph Banks – more than 41 years, from November 1778 until his death in June 1820. Now, you could be forgiven for thinking that this must have been a tranquil period, with the incumbent presiding over a Society free from disputes and loyal to the great figure at the helm, right? Wrong, as a new addition to our book collection helps to demonstrate.

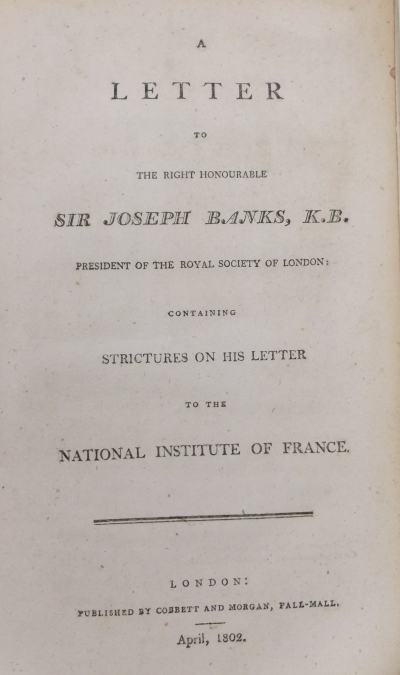

The title page of our new acquisition

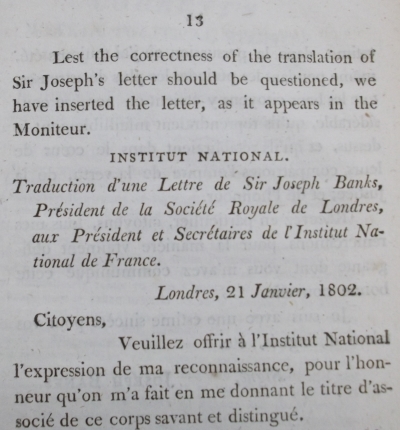

We recently used some more of our Robson bequest money to purchase from a book dealer a copy of an April 1802 Letter to the Right Honourable Sir Joseph Banks … containing strictures on his letter to the National Institute of France. Written by a gentleman styling himself ‘Misogallus’, this pamphlet, previously printed in Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, took aim at Banks, then just past the halfway point of his record-breaking Royal Society presidential term. Earlier in 1802, Banks had been elected an associate member of the Institute in Paris, prompting a thank-you note which expressed his appreciation of ‘the highest and most enviable literary distinction which I could possibly attain”, and his warm feelings towards “a nation which, during the most frightful convulsions of the late most terrible revolution, never ceased to possess my esteem’.

Caricature of Sir Joseph Banks PRS, from Peter Pindar’s satirical poem Sir Joseph Banks and the Emperor of Morocco, 1788 (ref. Tracts X420/19).

Now, you’d hardly expect all this fawning over Napoleon’s countrymen to go down well with ‘Misogallus’ (the clue’s in the name), and sure enough, Banks gets both barrels, his acceptance letter ‘not only so little honourable to your own character, but so insulting to the [Royal] Society over which you have long presided, and so repugnant to the genuine feelings of an Englishman’. Expressing ‘disgust at this load of filthy adulation’, Misogallus continues:

‘… the French Institute may perhaps be intoxicated by the incense which you have lavished before their altar of Atheism and Democracy; for, although they were companions of the respectable Buonaparté in his expeditions, and plundered libraries and cabinets with as much alacrity, and as little scruple, as he displayed in treasuries and in churches, I do not believe that the ungrateful nations whom they robbed ever composed such a brilliant eulogium on their talents and their virtues. No, Sir, it was reserved for the head of the Royal Society of London, to assure an exotic embryo academy that he is more proud of being a mere associate of the latter than President of the former.’

Ouch! So why this extreme disdain for Banks, who, in Misogallus’s words, has been carried away by ‘the impetuous torrent of [his] esteem which bears away the feeble impediments of loyalty, patriotism, morality, and religion’? Well, our book dealer provides a clue: his catalogue lists the work not under the author’s pseudonym but under [Horsley, Samuel?].

There’s that question mark, of course, but this would seem to fit: Samuel Horsley (1733-1806) was a mathematician who had been elected to the Royal Society in 1767, serving on Council for the five years immediately preceding Banks’s arrival in the presidential chair. He would therefore have been at the ringside for the fractious events at the Society during the early years of Banks’s presidency, which saw the Foreign Secretary, Charles Hutton (another mathematician, a class of natural philosophers who never ranked highly in Banks’s esteem) unseated in 1784, accused by the President of failing to carry out his duties properly. A flurry of pamphlet recriminations followed, including one from Secretary Paul Maty highlighting ‘instances of the despotism of Sir Joseph Banks … and of his incapacity for his high office’.

Horsley was also a senior clergyman in the Church of England – Bishop of Rochester at the time of the ‘Misogallus’ pamphlet – and would therefore have viewed Banks’s association with revolutionary French politics as an affront to the established religion, and a sign of worship at the ‘altar of Atheism’. All these historical grievances and contemporary political concerns seem to have found their focus in the extreme anger of the 1802 ‘strictures’; given this, it’s understandable that the diatribe didn’t find its way onto our Library shelves during Banks’s reign. We’re glad to have acquired a copy now, filling a gap in our collection … although I’m starting to imagine I can feel the glare of Sir Joseph’s eyes as I walk past his portrait!

Detail from page 13 of the Letter to the Right Honourable Sir Joseph Banks, showing the start of Banks’s letter in the original French.