Explore some early examples of peer review in Royal Society journals dating from 1669.

First rejection

This publication from 1669 represents the first confirmed instance of a scientific piece being rejected on the strength of a referee’s report. It details Oldenburg’s account of the reasons for not reading or publishing a paper by George Sinclair, on the grounds that the findings were not original. Oldenburg, the Royal Society’s first secretary and founding editor of Philosophical Transactions, said that Sinclair’s papers had been passed to Robert Moray and he reported that most of what was there had already been reported by Robert Boyle.

"...Sir Robert Muray affirms, that he did not at all judg them proper to be exhibited there, because they seem’d to him to containe nothing new or extraordinary” – Henry Oldenberg

Editorial manipulation

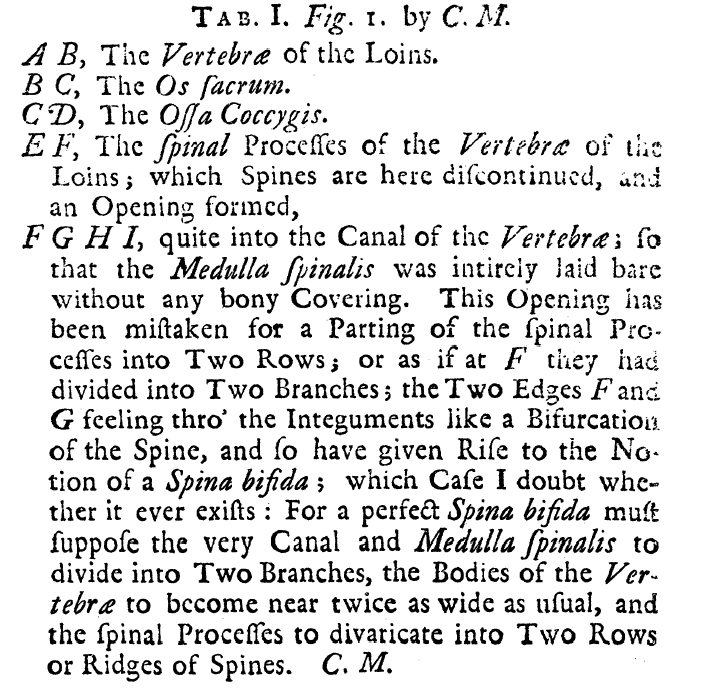

By the time we reached the 1740s, editorial comments were being added publications to distance them from the views expressed in it, or to modify the conclusions. This report by George Aylett, describing a putative case of spina bifida, has a note from the editor, Cromwell Mortimer, who wrote the legend to the figures observing that the case as reported didn’t appear to be a true spina bifida.

Getting serious

This is the first peer review report from the time when it really took off at the Royal Society, i.e. from 1831 onwards. The report was drawn up by William Whewell and John Lubbock on George Bidell Airy’s paper on the inequality in the long motion of Venus. Lubbock and Whewell’s report was printed in Proceedings of the Royal Society, along with their judgement that it should be published; it’s significant because it’s the Royal Society’s first experiment with systematic refereeing.

"We regard this paper as the first specific improvement in the solar tables made by an Englishman since the time of Halley…and we recommend its insertion into Philosophical Transactions” – Lubbock and Whewell