Rupert Baker is charmed by a new addition to the book collection, in which fairy tales are used to inspire a love of science and the natural world in young Victorian readers.

We’ve recently added a curious little item to our printed books collection, in the form of an 1879 educational primer for children, The Fairy-Land of Science by Arabella Buckley.

Buckley, whose interest in scientific topics developed during her 11 years as secretary to the geologist Sir Charles Lyell, went on to become a key figure in the nineteenth-century boom in popular science publishing, which extended to children as well as adults. Contrary to the Dickensian view of knowledge being ground into the heads of the young as a series of cold hard facts, fairy tales were among the many colourful methods used to promote a love of science and the natural world in Victorian childhood. As historian Melanie Keene notes in her recent book, also available in the Royal Society Library:

‘… the fairies and their tales were often chosen as an appropriate new form for capturing and presenting scientific and technological knowledge to young audiences … They demonstrate how, for many, the sciences came to replace the lore of old as the most significant source of marvel and wonder … Far from being the destroyer of supernatural stories about the world, through these fairy tales the sciences were presented as being the best way to understand both contemporary society and the invisible recesses of nature…’

While the front cover of Buckley’s book features an illustration of pixie-folk at work, designed to attract the younger reader, the fairies are not present in the engravings within, which show more realistic images of the natural world. The text, meanwhile, uses such imaginary beings as metaphors for the laws of science: ‘true fairies, whom you will love as much when you are old and greyheaded as when you are young … and though they themselves will always remain invisible, yet you will see their wonderful power at work everywhere around you.’

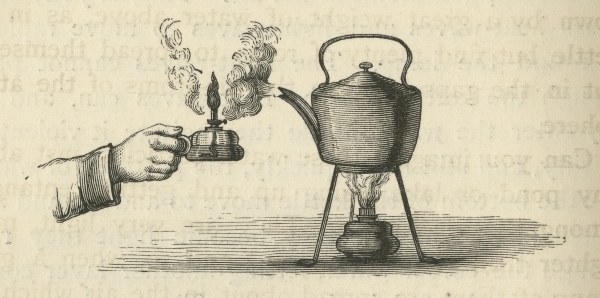

Illustration from Lecture IV, ‘A drop of water on its travels’

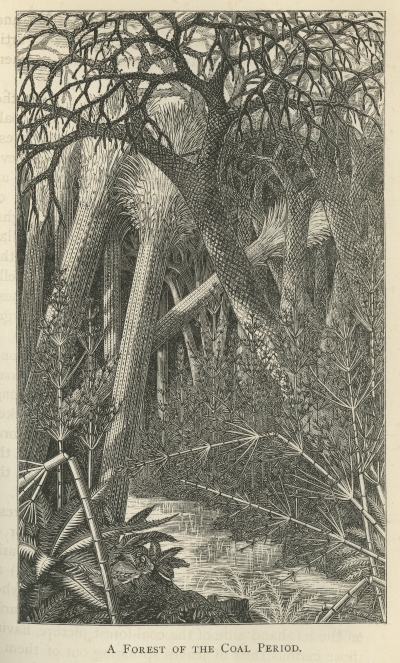

The key, in Buckley’s educational scheme, was to regard the fairy-land of science as ‘not some distant country to which we can never hope to travel. It is here in the midst of us, only our eyes must be opened or we cannot see it.’ She proceeds, via a series of lectures to her young audience, to look at the scientific explanations for such wonders as the ‘magical’ properties of sunbeams and the power of the sun, the changes undergone by a drop of water as it moves from ice to liquid to vapour, the life of a primrose, and the history of a piece of coal. I particularly like this image of ‘the gigantic trees of the coal-forests’ from the Carboniferous period:

Illustration from Lecture VIII, ‘The history of a piece of coal’

And, of course, the book ends with a good Victorian moral lesson on the final page:

‘We cannot watch the working of the fairy “life” in the primrose or the bee, without learning that living beings as well as inanimate things are governed by these same laws of nature; nor can we contemplate the mutual attraction of bees and flowers without acknowledging that it teaches the truth that those succeed best in life who, whether consciously or unconsciously, do their best for others.’

We acquired our charming and very well-preserved copy of The Fairy-Land of Science using some more of the legacy kindly bequeathed to us by Anne Ross Miller Robson in 2012 ‘for the purchase of books for the Library’ – previous purchases with this fund have included books by John Ray, Eleanor Ormerod and ‘Misogallus’. Do pop in to the Library to see our new acquisition and acquaint yourself with Arabella Buckley’s Victorian world, where ‘everything around you will tell some history if touched with the fairy wand of imagination.’

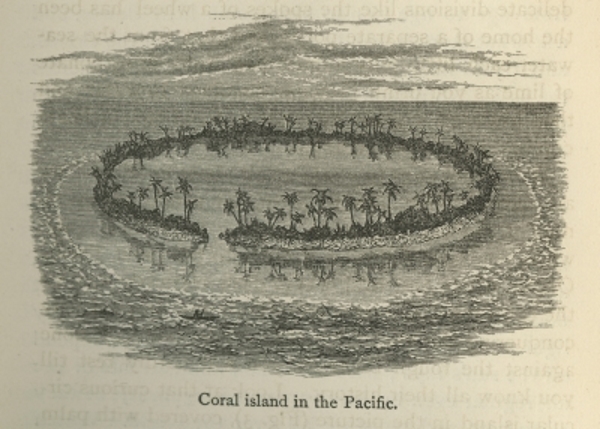

Illustration of a coral island, from Buckey’s introductory lecture on ‘how to enter the fairy-land of science'