The life of Seth Ward FRS, mathematician, astronomer and Bishop of Salisbury.

Does the name Seth Ward ring any bells with you?

Seth Ward, by John Greenhill, 1673-4 © The Royal Society

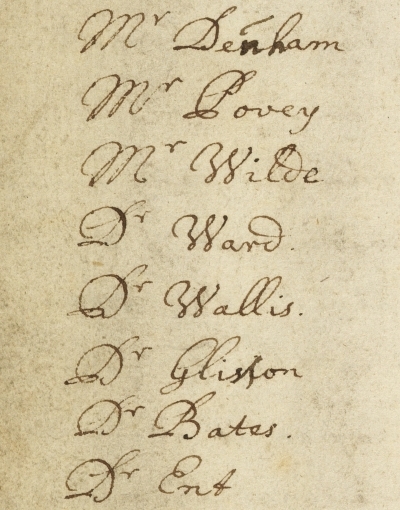

He’s one of those early Fellows of the Royal Society who had occasionally crossed my radar. If you visit our home in Carlton House Terrace you’ll see his portrait (above) hanging in reception, showing him resplendent in his Order of the Garter robes with the spire of Salisbury Cathedral just visible in the background. And he crops up on page two of our first Journal Book: in the list drawn up by the twelve Founder Fellows of ‘the names of such persons … whom they judged willing & fit to joyne with them in their designe’, here’s ‘Dr Ward’ halfway down the first column:

Royal Society JBO/1: details from the minutes of the first meeting, 28 November 1660

That was pretty much the extent of my knowledge of Seth Ward until recently. However, his name seems to have popped up with some regularity in our recent antiquarian book purchases and my leisure time reading, so I thought I’d find out a little more about his life and work. This may just be an example of the frequency illusion, of course (cue the cognitive scientists’ joke: I’d never even heard of the frequency illusion till last week, and now I’m seeing it everywhere!) but Ward proved to be an interesting character, well worth a closer look.

Born in 1617, raised in the Hertfordshire town of Buntingford and educated in Cambridge at Sidney Sussex College, Seth Ward showed an early aptitude for numbers: ‘his genius lay much to the mathematics, which being natural to him, he quickly and easily attained’, according to John Aubrey in Brief lives. This led to his appointment in 1649 as Savilian Professor of Astronomy and a move to Oxford, where he worked on theories of planetary motion (culminating in the publication of Astronomia geometrica in 1656) and made the acquaintance of John Wilkins at Wadham College.

This put Ward, along with Wilkins, John Wallis and other Oxford academics, in the firing line when criticisms of the university curriculum were made in the 1650s by Thomas Hobbes, John Webster and others. Ward’s initial response came in 1654 with his book Vindiciae academiarum, a copy of which we purchased at an auction in November last year, using some of the remaining funds from our Robson bequest for antiquarian book-buying.

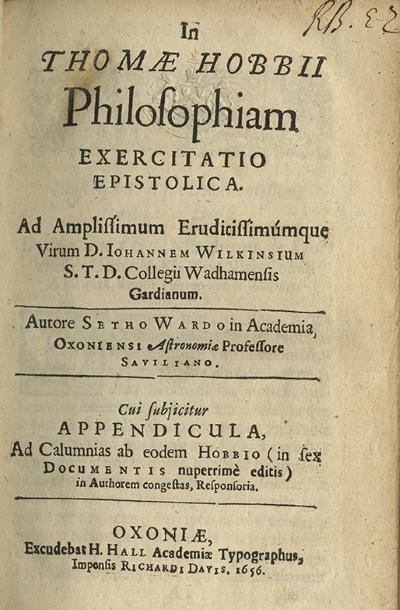

The dispute over university education became part of a wider, long-rumbling and extremely fractious argument commonly referred to as the Hobbes-Wallis controversy. Hobbes fired the next broadside in his 1655 work Elementorum philosophiae, to which Ward (encouraged by Wallis) responded a year later with In Thomae Hobbii philosophiam exercitatio epistolica – another book missing from our collections until recently, when we spotted a copy in an antiquarian book catalogue and used the very final pennies from the Robson bequest to snap it up. Here’s the front page, complete with praise for Wilkins at Wadham College:

I won’t attempt to explain the full details of Hobbes-Wallis – it’s rather complicated and I don’t pretend to understand it all – but suffice to say Hobbes is not in the 1660 list of ‘willing & fit’ fellow-travellers for the proposed new experimental society, and never became an FRS (or squared the circle), though we do have a splendid Hobbes portrait donated by Aubrey, his Wiltshire neighbour and friend. Seth Ward’s career, meanwhile, was moving in a more pious direction: he was consecrated Bishop of Exeter in 1662, and moved on five years later to become Bishop of Salisbury, a post he held until his death in 1689.

Ward’s religious life, and his ‘strong, methodical and clear’ sermons, are chronicled in a posthumous biography by Walter Pope FRS, The life of the Right Reverend Father in God Seth, Lord Bishop of Salisbury. I was alerted to the existence of this work when I read an article by my colleague Noah Moxham, who describes it as an ‘idiosyncratic memoir’. Idiosyncrasies notwithstanding, this sounded like a book we should have on our shelves, so I was pleased to spot a copy (‘firmly bound with bright and clean pages’) on the AbeBooks website, and we made the purchase.

There are also many snippets on Ward’s later years in Ruth Scurr’s fascinating John Aubrey: my own life, which I’ve just finished reading. He crops up in 1669, pushing the first wheelbarrow of earth to launch a project to improve the navigability of the River Avon; and he’s mentioned under his ecclesiastical title in July 1678 in the context of the universal language debates of the time: ‘Andrew Paschall … asks [Aubrey] to assure Mr Lodwick that his proposals are intended to agree with the framework for the Real Character set out by the Bishop of Sarum’.

Then, after Ward’s death in 1689, his manuscripts were saved by Aubrey from a terrible fate: ‘I have rescued some of Seth Ward’s scattered papers from being used by the cook to put under pies’. This recycling of past treasures for mundane purposes seems to have been a vexing issue for early antiquaries and proto-archivists such as Aubrey, who, in his Wiltshire childhood, was already lamenting how ‘a world of rarities has perished hereabouts … it hurts my eyes and heart to see fragile painted pages used to line pastry dishes, to bung up bottles, to cover schoolbooks, or make templates beneath a tailor’s scissors.’

Fortunately, Aubrey’s prompt action appears to have rescued at least some of Ward’s work, which now resides in Salisbury Cathedral Library and the Bodleian. He mostly features in Royal Society archives as a name in the minutes of the early meetings – according to historian Michael Hunter, Ward made ‘regular attendance and occasional contributions till 1675’, but was ‘barely active thereafter’, presumably busy with ecclesiastical matters. While he’s not one of the major players among the early Fellowship – there’s no Ward’s Law or Ward’s Comet to immortalise his name – Seth Ward strikes me as being a valuable member of the chorus line in that cast of gentlemen philosophers, curious about every aspect of the world, who got the Royal Society off to such a flying start, and we’re glad to have increased his presence in our Library collections.