The latest theme issue of Philosophical Transactions B examines the identification, ecology, drivers of change, and human use of tropical savannas and grasslands.

What are tropical grassy biomes and how are they distinct from other world biomes?

Tropical grassy biomes are defined by the grasses that dominate the ground layer. Generally, these grasses utilise the C4 photosynthetic pathway. While the C4 photosynthetic pathway evolved over 20 million years ago in grasses, this biome expanded across the tropics around 3-8 million years ago.

This new plant functional type brought with it novel ecological pressures in the form of frequent fires and mammalian herbivory. In these biomes, plant species must be tolerant of heat and water stress, fire and/or being chowed on mammalian herbivores such as elephants, rhino and herds of zebra and wildebeest.

What ecosystem services do tropical grassy biomes provide?

They provide a diverse set of services – they supply food, water, medicines, energy (wood and charcoal), fodder for cattle and building supplies (timber and thatching grass) through to the less tangible cultural and spiritual services to many millions of people across Africa, Asia, Australia and South America. On a global scale, they house an important component of the world’s biodiversity, store 15% of the world’s carbon and play a critical role in regulating carbon and nutrient cycles.

Why care about tropical grassy biomes?

These biomes were the cradle of human evolution, and in our contemporary world, they support the livelihoods and wellbeing of over one billion people. With the population of Africa alone set to treble by 2050, the continuing pace of climate change, increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations and increasing agricultural development, there is an urgent need to understand the unique ecology of these systems.

Why have tropical grassy biomes been neglected despite their importance?

Policy and political will for action on the environment has long been with tropical forests for their biodiversity and carbon values. Meanwhile, tropical grassy biomes are often perceived as degraded ecosystems, although this is now changing.

What threats do tropical grassy biomes face?

The most evident form of environmental change is probably the intensification and changing frequency of the El Nino, bringing severe drought to parts of Southern Africa and Madagascar leading to crop failures and crises in food security for millions. Other key threats are loss of mega-herbivores such as elephant and rhino, policies of fire suppression, increasing land use intensity for agriculture and wood extraction, planting of trees in afforestation programs.

Why is it essential to model tropical vegetation?

We can’t look into the future, but we can develop global vegetation models that synthesise our best understanding of the ecological and physiological processes that create the patterns of vegetation we see today. These models are used to make predictions about how vegetation will change in the future as these changes have important consequences for biodiversity, climate, the carbon cycle and directly for us as human beings. Most of the world’s poorest people live in tropical regions, and these regions are changing rapidly. If we want to manage and adapt to these changes we need to know the drivers of change, and what sorts of futures we are heading towards.

What are the problems with current models? And how can we tackle those problems?

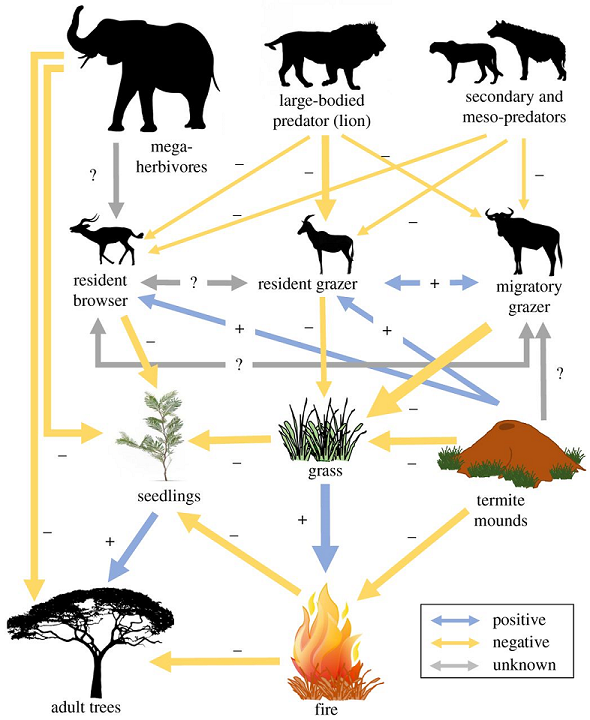

In my mind, as an ecologist not a modeler, there are three key issues. Firstly, people. How do we better integrate the role of people when modelling scenarios of vegetation change? Secondly, disturbance. For a long time, vegetation models were built on the assumption of a deterministic relationship between vegetation, climate and soils. The role of fire and herbivory are increasingly recognised as crucial to understanding the limits and dynamics of biomes, but the way in which fire and herbivory are incorporated in models can be ecologically naive. Fire is a complex process bound by inter-relationships with vegetation and climate. Modelling these feedbacks that operate across temporal and spatial scales is immensely challenging. And finally, dynamics and evolution of vegetation.

Most models of vegetation define the limits of biomes based on archetypal types of plants, or even just the greenness of a landscape, which neither represents the diversity of vegetation nor does it represent the capacity for biomes to evolve over time. Even 100 years from now, the vegetation of the tropics, especially tropical grassy biomes, could look radically different to today. Great advances are being made in this field by researchers developing models that represent suites of plants traits of vegetation, how they combine, and allowing these trait mixtures to evolve. More complex models with evolving vegetation are very exciting, but we must also ensure they connect with reality.

Dr Caroline Lehmann is a lecturer in biogeography in the School of Geosciences at the University of Edinburgh.