Keith Moore provides a snapshot of the work of Arthur Mason Worthington FRS, pioneer of high-speed photography and a talented artist with both pen and camera.

We often speak of books, movies or their successful authors making a bit of a splash. Although you may not have heard of Arthur Mason Worthington (1852-1916) you will instantly recognize what he’s best known for. Worthington was a pioneer of high-speed photography and his academic work was all about impact.

Whether it is the slow-motion flight of a bullet (and even potato gun versus watermelon) or small-scale reconstructions of dinosaur-busting meteor strikes, the telescoping of time around a rapid-fire event retains its ability to fascinate. ‘Bullet time’ and slow-mo are now movie special effect staples and your average superhero couldn’t do without them. But Arthur Worthington produced brilliant images at a time when he was still describing the industry as the ‘kinematograph’.

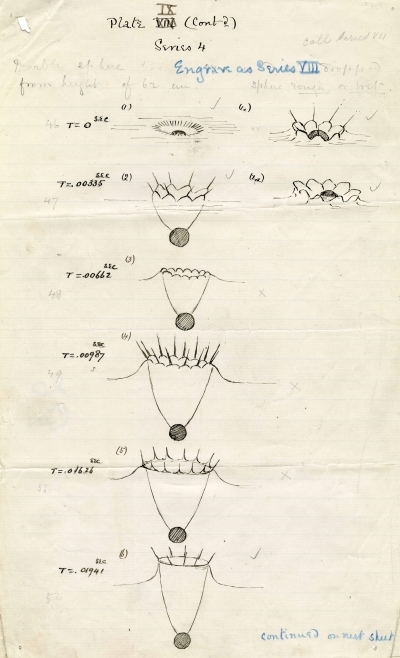

What originally caught my attention about Worthington’s science was the simple elegance of his draughtsmanship. We have many of his line drawings of high-speed physical events, produced as illustrations for Royal Society journals. For example, what happens when a drop of milk or a ball of marble falls into a liquid? I enjoy the way that Worthington refused a left-to-right reading of such events, in favour of a sequence of top-to-bottom figures, drawing the eye downwards with gravity, or scrolling in the manner of a reel of film. Worthington captured these images in flashes – literally – working in the dark using a short duration electric spark and repeating an observation until he could produce a sketch of the key elements of a transient event.

Splash drawings by Arthur Worthington, 1882

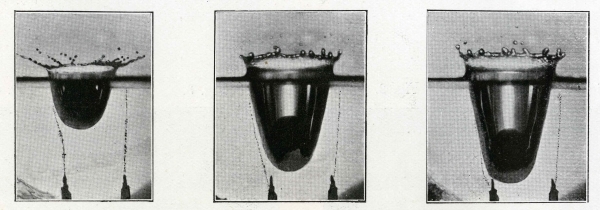

By 1896, Worthington had improved his techniques so that he could capture high quality photographic images of very precise details. He released a metal timing sphere at the same instant as his splash-droplet; triggering an illuminating Leyden jar spark for his open-shuttered camera. However, Worthington remained frustrated by the limitations of the Royal Society’s plate-makers, the Direct Photo-Engraving Company, who persevered in reproducing his pin-sharp images as grainy eye-strainers. In publishing his paper ‘Impact with a liquid surface, studied by the aid of instantaneous photography’ (part I and part II), there commenced a long and increasingly short-tempered correspondence between the Society, its printer and the scientist.

Who dropped the ball? Royal Society plate figures, 1900

A genuinely talented artist with a pen or camera, Worthington complained mightily about his own figures. In the preface to his book A study of splashes (1908) he wrote ruefully that ‘in the illustrations printed by the Royal Society much of the beauty of the original photographs was lost in the reproduction, or was sacrificed in a selection of which the only object was the elucidation of points of technical scientific interest’. In his own book, he could (and did) better approximate what he wanted, and it is curious to find a scientist arguing for the importance of aesthetics as well as science.

But Arthur Worthington went just a little further, perhaps to reward himself, and his readers, for the annoyances of the past. I was delighted to see that he had decorated his volume with a ‘crown splash’, based upon his own photographs. Truly a crowning achievement, and I’m now on a hunt for similarly beautiful gilt-stamped scientific book-bindings. I’ll let you know what I find!

A study of splashes, cover detail, 1908