Adele Allen explains how research into sleeping sickness and radiation gave rise to some interesting parcel deliveries in the early twentieth century.

As Christmas approaches, many of us will be resorting to some internet shopping to tick off the names from our present lists. However, a delve into the Society’s correspondence shows us items which would make less welcome additions to your Christmas stocking. For example:

‘Dear Dr [Frederick] Mott, I am sending you by parcel post another box from Capt Greig, presumably containing brains. Please acknowledge its receipt…’ (16 February 1904, NLB/28/106)

We are all familiar with the joys of waiting in for a delivery, but how many of us can say that the parcel has contained, presumably or otherwise, brains! This striking missive, from Royal Society Assistant Secretary Robert Harrison, leads us to the Society’s investigations into sleeping sickness in the early 20th century.

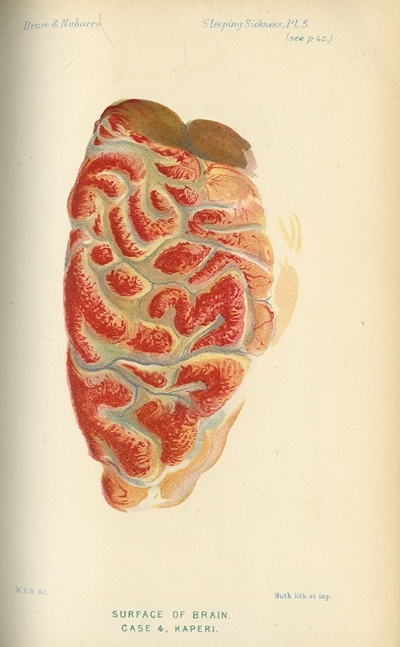

Human brain affected by sleeping sickness, from a report of the Royal Society Sleeping Sickness Commission, 1903.

A deadly epidemic occurred in Uganda in 1901, firing up the scientific community and leading the Royal Society to establish a number of Sleeping Sickness Commissions, whose reports were published between 1903 and 1919. Colonel David Bruce, a celebrated pathologist and microbiologist, identified Trypanosoma brucei, a species of parasitic protozoan, as the cause of trypanosomiasis in cattle; he further pointed to the tsetse fly as the insect vector, transmitting the disease between mammal hosts. While this discovery was made in 1899 in South Africa, it was not until in 1903, following the sleeping sickness outbreak in Uganda, that the link between trypanosomiasis and human sleeping sickness was confirmed.

‘Sir D. Bruce Director of the commission in his canoe on Lake Victoria’: from a photograph album compiled by Colonel Albert Ernest Hamerton (1873-1955), documenting the Royal Society Sleeping Sickness Commission, Uganda, ca. 1909 © The Royal Society.

Bruce, along with other key players in the commission, including Dr Nabarro, Captain Greig and Frederick Mott, travelled to Uganda to undertake the dangerous work involved in the study of sleeping sickness. They were able to make practical suggestions aimed at halting the alarming spread of the disease, such as preventing men from infected areas being employed in non-infected zones, and vice versa (NLB/28/183).

Study of the disease was not, however, limited to Uganda – Archibald Geikie, Royal Society Secretary, wrote to the Foreign Office in 1904 to discuss the logistics of transporting four infected patients to England, with two to be treated by Sir Patrick Manson at the London School of Tropical Medicine and the others by Professor John Rose Bradford and Professor Sidney Martin at University College Hospital (NLB/28/196).

Another rather unusual and anxiety-inducing postal delivery is noted in the correspondence from 1906. In October of that year, Harrison wrote to Émile Armet de Lisle, as the individual responsible for preparing and dispatching radium, noting that he had not heard from him recently and seeking assurance that no accident had occurred to cause the long delay in dispatch (NLB/33/604). Fortunately for all concerned, no one was harmed in the posting of this particular parcel, at least in the short term, and de Lisle’s preparation of radium arrived safely on 20 November.

The actual sourcing of the radium on which de Lisle was to work, reducing the residue into the various radioactive compounds, was a challenge in itself. Assistance in this task came from no less a personage than the Prince of Wales, who helped Sir William Huggins to obtain from the Austrian government, for the princely sum of £66.10s, a supply of 500kg of residues from the Uranium works at Joachimsthal (NLB/34/13).

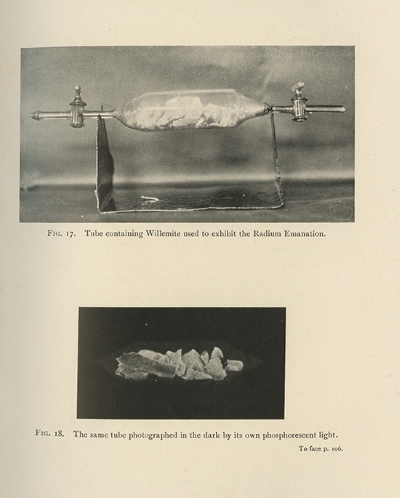

Plate from Frederick Soddy’s The interpretation of radium, 1909.

The minutes of the Radium Investigation Advisory Committee in May 1904 (CMB/11) give further evidence of the international nature of such work, with Professor Living writing to the Secretary of the Vienna Akademie for advice on obtaining residue from the Imperial Uranium Works, and also to the Manager of the Uranium & Rare Metal Company in Buffalo, New York, to enquire whether they could supply radium products. The Society’s work on radium could not have proceeded were it not for the grant of £1000 from the Goldsmiths Company for ‘aiding the prosecution of original research work in connection with the character and properties of radium…’ (CD/16).

Prior to an understanding of the intense radioactive nature of radium, the product was used in a range of everyday products, including toothpastes, due to a belief in its curative properties. With this in mind, an accident befalling a package was perhaps the least of one’s worries.

So, I hope any ‘attempted delivery’ cards that do drop on your doormat in the coming weeks promise rather more appealing contents than brains or radioactive substances!