The Royal Society promotes excellence in the teaching of science, mathematics and computing while also encouraging and supporting investigative work in the classroom. On this page you will find details about the different schemes and opportunities you can get involved with and you can explore our free resources.

For further information or if you have any specific questions, please contact the Schools Engagement team at education@royalsociety.org. To receive updates about all our programmes, resources and funding opportunities, please sign up to our UK teachers newsletter.

Explore our resources

Brian Cox school experiments

The Royal Society presents video resources featuring Professor Brian Cox presenting experiments…

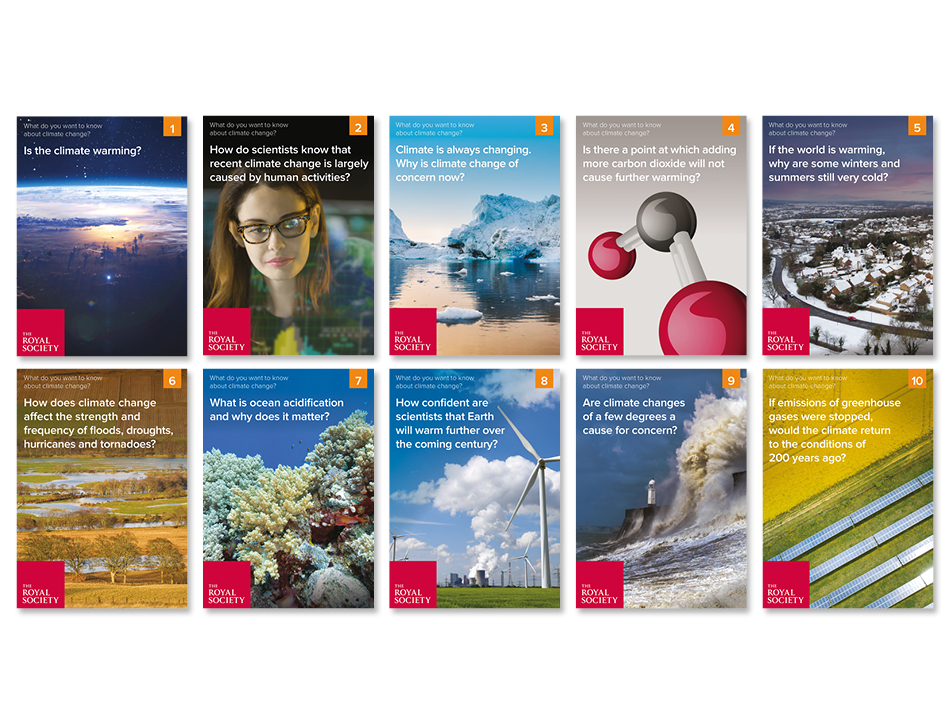

What do you want to know about climate change?

This resource is based on the latest evidence available to scientists and has been adapted from…

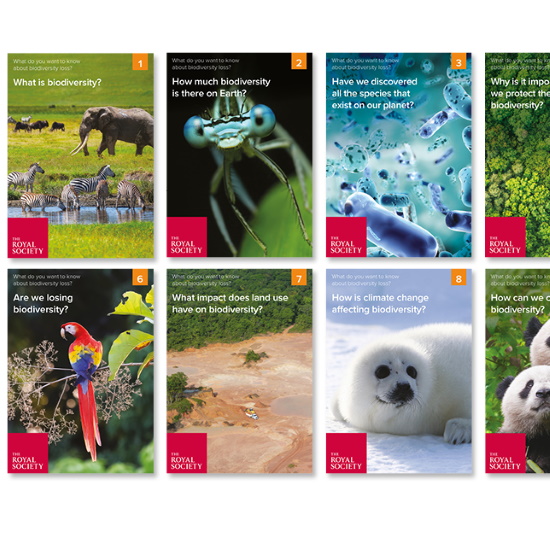

What do you want to know about biodiversity loss?

This resource is based on the latest evidence available to scientists.

Why science animations

Animations aimed at school aged students to highlight the benefits of scientific study and the…

Global challenges

Curriculum linked resources to support the teaching of climate science and sustainability.

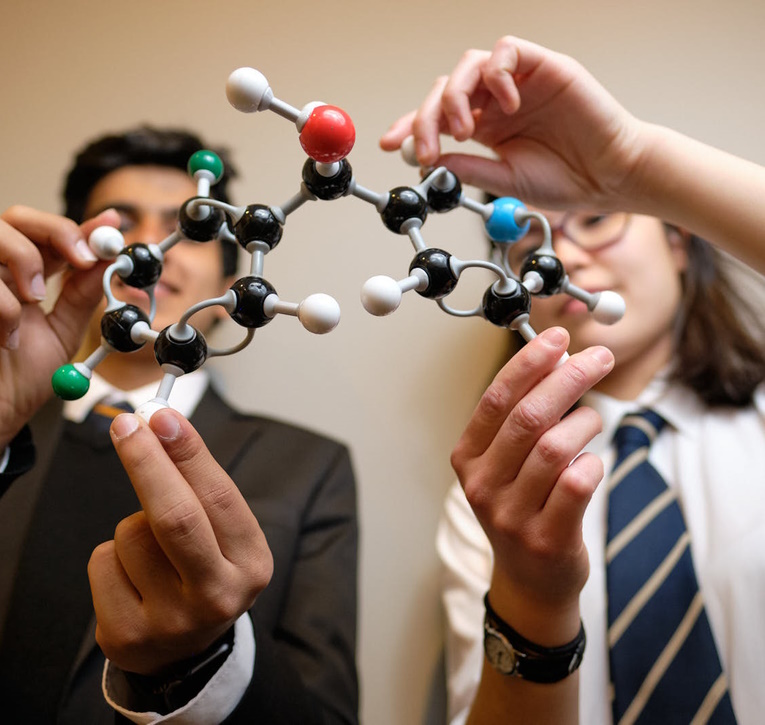

Animate materials resources

Resources to support the teaching of materials at primary and secondary level

Machine learning resources

The Royal Society contracted the British Science Association to produce a series of CREST…

Your Planet, Your Questions video clips

Aimed at students aged 5 to 14 the Your Planet, Your Questions event took place in June 2021,…

Young People's Book Prize school resources

Free resources to use in the primary school classroom

Inspiring scientists

Explore diversity in science

Factsheets - future science

Explore factsheets on some of the latest work by the Royal Society. Content may be used to enhance…

Shared resources from our Schools Network

Sharing curriculum linked resources, identified by teachers in the Royal Society Schools Network,…

Partnership Grants

Schools can apply now to receive up to £3,000 to run an investigative STEM project in partnership with a STEM professional from academia or industry. Free online sessions are being run to introduce teachers and STEM partners to the scheme and application process.

Tomorrow's climate scientists

An extension to the Partnership Grants scheme which aims to give students not just a voice but an opportunity to take action themselves to address climate and biodiversity issues – to become the climate scientists of tomorrow.

Recent blog posts

View all posts

Ruby Seger-Bernard

In News and views

3 min read

Royal Society resources to support the teaching of practical science

Outlining the Royal Society's resources for schools and teachers to use to support the teaching of…

Sir Adrian Smith PRS

In News and views

3 min read

Planning for turbulence: why the UK needs a long-term science strategy

Royal Society President Sir Adrian Smith writes on why a long-term vision for science is needed in…

Professor Ulrike Tillmann FRS

In News and views

2 min read

Transforming education would deliver opportunity for all: we can’t waste this chance

Professor Ulrike Tillmann FRS discusses a once in a generation opportunity to be bold and create…