Open access to research outputs has been the single biggest issue in the evolution of science publishing over the last couple of decades.

Open access to research outputs has been the single biggest issue in the evolution of science publishing over the last couple of decades. Since the early days of open access in the 1990s things have moved a long way and it is estimated that at least 28% of the scholarly literature is now open. For 2015, the proportion was as high as 45%.

The arguments in favour of open access have been well rehearsed: research funded by the public purse should be available to the public; open access articles receive more downloads and more citations than paywalled articles; removal of barriers to reading and re-use allows the fruits of research to be more fully exploited and for knowledge to advance more quickly. But, of course, there are also many challenges to overcome. Principal among them is probably finding a model of open access that is genuinely sustainable, that doesn’t freeze out authors in lower income countries and that doesn’t jeopardise the process of quality assurance by peer review.

Right now, publishers are in the midst of a transition from the traditional subscription model to a variety of models some of which charge authors, their funders or institutions, some of which are funded collaboratively (such as OLH and SCOAP3) and still others yet to be developed. Which of these will ultimately prevail is not yet clear, particularly as there is considerable variation in national and funder policies around the world and in the degree to which different funding streams are available and committed to open access.

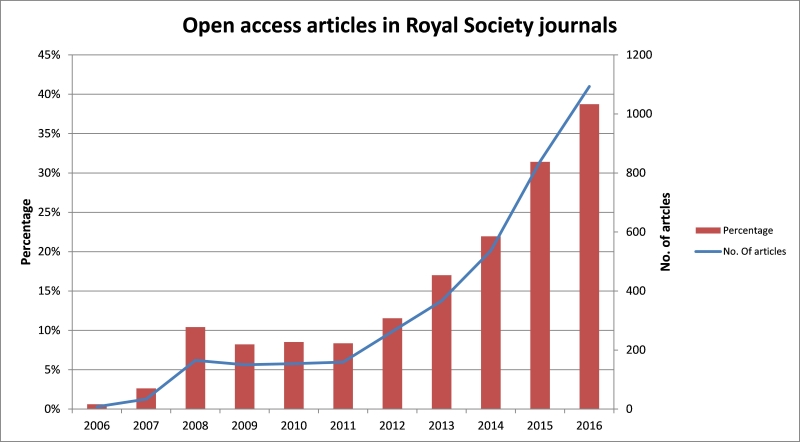

Here at the Royal Society we introduced open access publishing as an option for authors in all our journals in 2006. This initiative (following an APC model with a CC-BY licence for articles) was welcomed by authors at the time and the proportion of authors choosing this option has risen steadily ever since (see graph). While some authors undoubtedly choose open access on principle, most probably do so in order to comply with their funder requirements. Indeed in the early years of open access at the Royal Society, most authors selecting this option were funded by Wellcome and it’s probably no coincidence that there has been even more marked growth since the introduction of open access policies by the UK Research Councils and many other major funders.

In 2011, we ventured beyond the hybrid model and launched our first open access journal, Open Biology. This was followed three years later by the launch of Royal Society Open Science. Taking our eight hybrid journals and our two fully OA journals together, we have seen particularly rapid growth in recent years and in 2016, almost 40% of our articles were published with immediate open access. Even taking the hybrid journals alone, the proportion is 24%. This is considerably ahead of most publishers and probably reflects, to some extent, the disciplinary coverage of our journals and the variation in popularity of open access across those disciplines.

The theme of this year’s Open Access Week is ‘open in order to…’ with researchers being invited to finish the sentence. As the UK’s national academy of science, we would say ‘… to maximise the impact and benefits of research.’ We are committed to the principles of open science. We have embraced open access in our own journals and expect continued growth as more and more funders and institutions align their policies towards a fully open future.

Open Access Week 2017 is 23 – 29 October, during which all of our content will be free to use. Start your search.