Why did H.G. Wells make a financial appeal to the Royal Society Council in 1920? Keith Moore investigates.

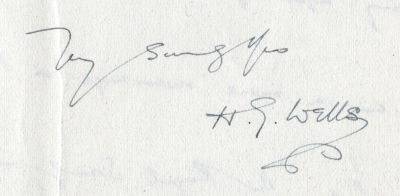

It’s always a nice coincidence when our activities happen to coincide with my own favourite topics (honestly, I don’t plan this). Recently, I was delighted to come across an unnoticed file of 1920s Royal Society Council documents containing an apparently routine appeal for financial help. Turning through the letters, I was stopped short by a very familiar hand and signature – the English author Herbert George Wells (1866-1946). Now whatever in The War of the Worlds was he up to?

Signature of H.G. Wells (Royal Society CD/109)

I should say that we have an upcoming conference in September 2018 on the impact of the First World War on scientists and their international institutions: so, the research was genuine, if the outcome a little more to my liking than expected (I’m an H.G. Wells fan). The Council file commenced with a letter from Petrograd (St Petersburg), sent by the radiographer Mikhail Isayevich Nemjonov to the Royal Society’s President and fellow-physicist J.J. Thomson. Politely, it drew the Royal Society’s attention to the isolation of Russian scientists caused by the continuing naval blockade of the nation.

Not surprisingly, Wells’s follow-up letter was a little more forthright. The writer was brimming with ideas and impressions from his visit to Russia in September and October of 1920 – guided by his friend Maxim Gorky he famously interviewed V.I. Lenin – and by 1921 Wells had published Russia in the Shadows. The assessment he arrived at in the book was unvarnished: ‘the administrative, social, financial and commercial systems connected with it have, under the strains of six years of incessant war, fallen down and smashed utterly’. Naturally, he wanted something done.

H.G. Wells (public domain image)

In his 1920 letters to the Royal Society, Wells rehearsed some of the snapshots of scientists that appeared in his book, but with practical intent: ‘Many of these men are still continuing Research work – with dwindling apparatus and material and in rooms often only a degree or so above freezing point. Like everyone else in Petersburg, they are in very considerable danger of starvation during the coming winter…’ His aim was to galvanise a relief effort for the Northern commune’s House of Science: food, clothing and scientific literature.

The situation was indeed serious, but it is difficult not to be warmed by the Kippsian enthusiasm of Wells’s pen running away with itself, rattling off his wants from the Royal Society: ‘they are…in great need of warm underclothing, boots etc., in fact every sort of haberdashery.’ The Society’s Fellows, confronted by his list of demands and with no experience whatever in running a relief effort for thousands of people, were nonplussed. Luckily, they were excused from helping artists. Wells asked that his letters be typed and copied over to the British Academy: ‘That body, it seem to me, is the one which can best undertake the relief of the House of Literature and Art’.

Ivan Pavlov ForMemRS and dog (RS.14171)

The cautious response was exasperating: ‘Deeply as I respect the Royal Society’, complained Wells, ‘I cannot have people like Pavloff starving…’ In the end, a newly created independent group of Royal Society and British Academy luminaries would take on the task. H.G. Wells and his great friend Sir Richard Gregory FRS, along with Arthur Schuster, Charles Scott Sherrington and Arthur Eddington, signed an appeal (published in Nature, the British Medical Journal and other periodicals) as the British Committee for Aiding Men of Letters and Science in Russia.

And who should you call in a crisis? Well, I was most happy to discover that the Committee’s chief organiser was a librarian: Sir Charles Hagberg Wright (1862-1940) the long-serving brains behind the London Library. Now you know!