Keith Moore explores the art and afterlife of a celebrated natural history work by Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon.

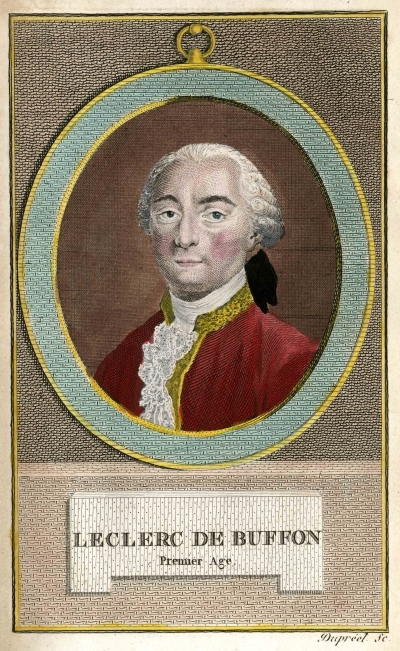

Recently, I was re-reading In a Glass Darkly, short stories by the Irish Gothic writer Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873) and found myself amused by an unlikely aristocratic get-together. The celebrated French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707-1788) was cited by none other than Mircalla, the Countess Karnstein, (c.1678-1872) the eponymous revenant of the story Carmilla. I don’t recall Buffon’s views of nature figuring too heavily in the Hammer Horror movie version (The Vampire Lovers, 1970) but I do feel a Buffon the Vampire-Slayer fan fiction mash-up is long overdue.

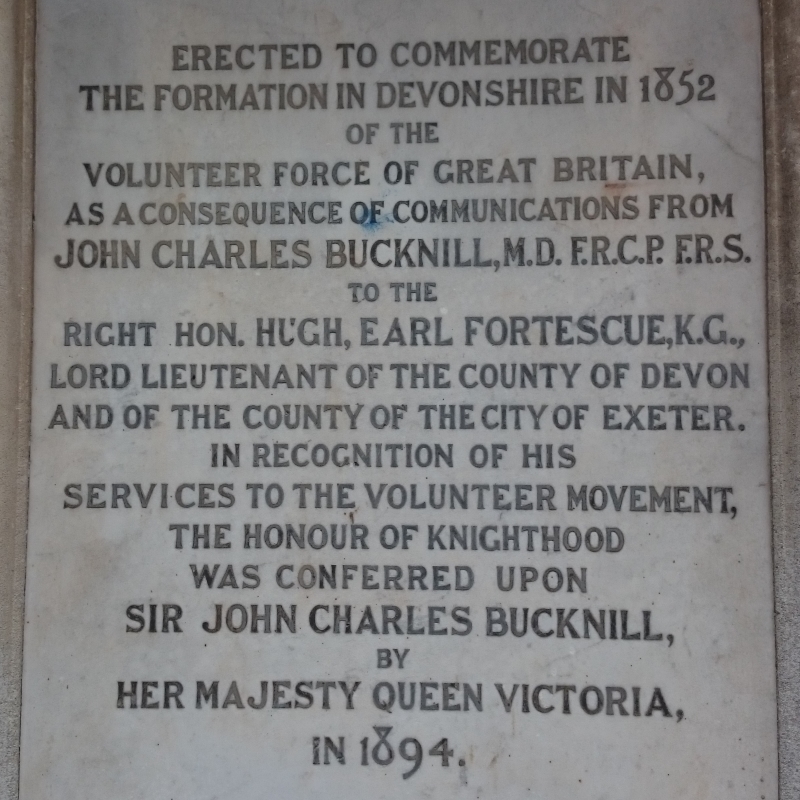

Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon: frontispiece plate from the Histoire naturelle (nouvelle edition, volume 1: Paris, 1799)

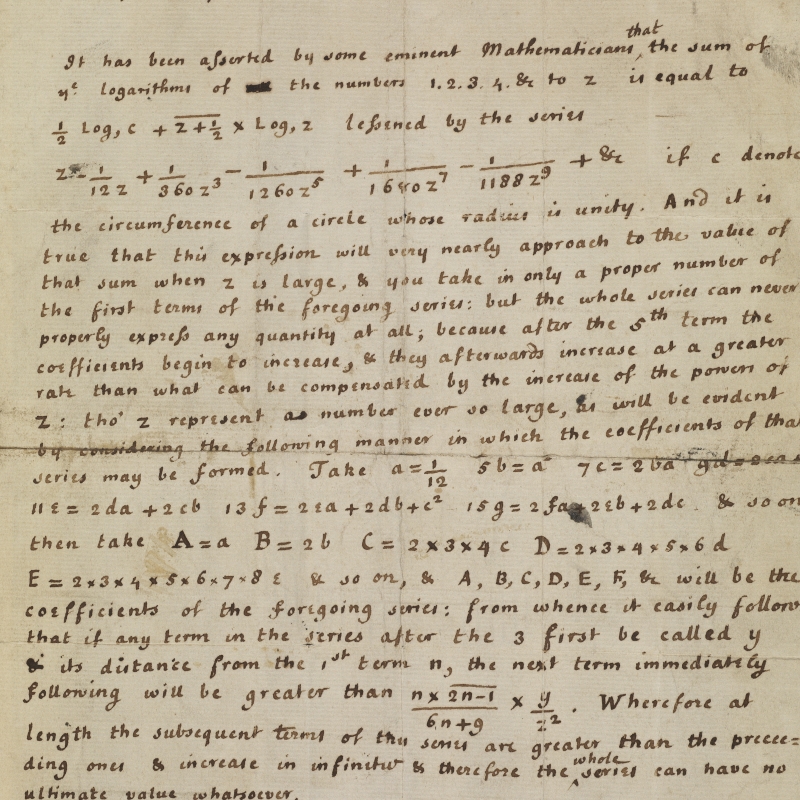

Once you’re primed to see something, you do start to see it everywhere. Because I’ve been cataloguing and scanning the marvellous etchings from Carmilla’s favourite reading, Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, généralle et particuliére, avec la description du Cabinet du Roi (1749-1789), I’ve begun to realize just how artistically influential this monumental work of natural history became and what an afterlife it had – a bit like Carmilla’s if you like. To date, my favourite repurposing of the book isn’t Le Fanu’s, but one by the twentieth century’s Spanish great, Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

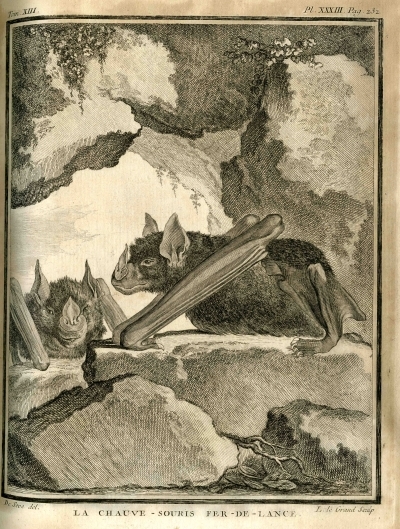

The original engraved and etched plates of animals, birds and reptiles made to accompany Buffon’s text were the work of a team of artists and engravers, led by the illustrator Jacques de Sève (fl.1742-1788). They are strikingly bold and beautifully produced – it would take a brave artist to attempt to improve upon the originals. Picasso’s Eaux-fortes originalle pour des textes de Buffon (1936, published 1942) tried to do just that. The idea came from the art dealer Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) and Picasso eventually selected thirty-two of Buffon’s creatures for reimagining as limited edition aquatints.

The Spaniard was capable of capturing an animal by a few strokes of the pen, or even by merging a bicycle seat and handlebar to ‘find’ a Bull’s Head (1942). His Buffon prints are entertaining character studies, veering from the savage to the comical, placing the movement and physicality of each animal to the fore in a way that the more static eighteenth century plates could not.

Picasso was neither the first, nor the last, to use the French Count’s encyclopaedia of nature. You can find anything from cheap nineteenth century woodcut versions of his artists’ plates to fine art masterpieces that take it for inspiration. Max Ernst (1891-1976) produced his own Histoire naturelle (1926) print portfolio and if the title isn’t a giveaway, then the side-on formality of its handful of animal drawings must be a nod to Buffon’s originals.

So there you have it – I hope I’ve made the case for this work of eighteenth century nature and I’d like to see many more artistic tributes to it. In my eyes at least, and quite apart from his scientific merits, Count Buffon has risen from the engraved.

La chauve-souris fer-de-lance (vampire bat), from Buffon Histoire naturelle vol. 13 (1765), plate 33