The Royal Society Library has partnered with the Cambridge University Digital Library to make key scientific papers by Isaac Newton freely available to all.

Last December, UNESCO added Sir Isaac Newton’s scientific and mathematical papers to their International Memory of the World Register. The papers are dispersed between Cambridge University Library, the Fitzwilliam Museum, Trinity College (Newton’s Cambridge alma mater), and the Royal Society archives – you can read more on the fascinating journey of his theological papers.

Newton served as President of the Royal Society between 1703 and 1727 and his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica – generally known as the Principia – was printed under the Royal Society’s seal. No wonder, therefore, that he left his mark (including some hair) all over the Royal Society’s archive.

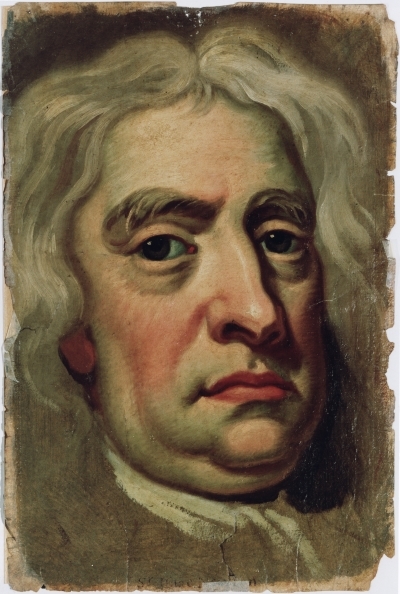

Portrait of Sir Isaac Newton by John Vanderbank, 18th century (P/0093 © The Royal Society)

To honour the UNESCO recognition, we have partnered with the Cambridge University Digital Library (CUDL) to make the scientific papers listed on the Memory of the World Register freely available to all, in one place. Digital platforms with open standards such as CUDL support specifically the capacity to bring together heritage dispersed between institutions. Images and descriptions come from the Royal Society, the system was developed by Cambridge University Digital Library, and the transcription of the correspondence comes from the Oxford-based Newton Project. This type of collaboration, made possible by digital tools, opens up science to all and is one of the most rewarding aspect of my role as Digital Resources Manager.

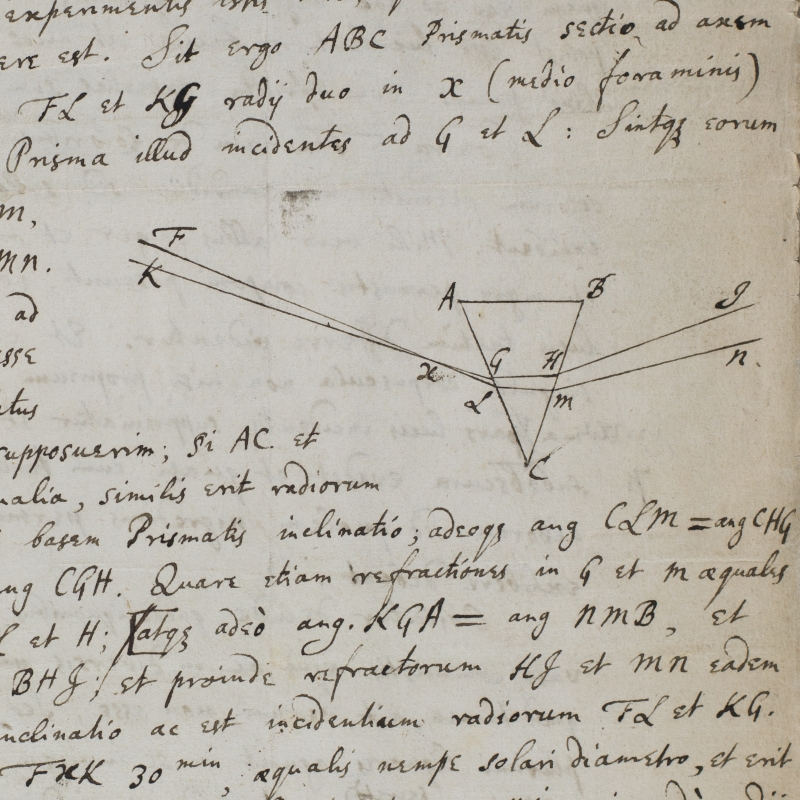

For the first instalment of our virtual collection of Sir Isaac’s scientific papers, launched a few weeks ago, we have included the manuscript version of the Principia (MS/69) and a series of letters (EL/N1/35-65) by Isaac Newton to various Royal Society Fellows, discussing a range of scientific subjects.

For anyone visiting the Royal Society archive, seeing the manuscript version of Sir Isaac Newton’s Principia is always a special moment. Just take a look at astronaut Tim Peake’s smile when he held the volume to celebrate the fact that his space mission was being named Principia!:

Tim Peake holding the Royal Society’s Principia manuscript

For scientists who casually refer to Newton’s laws of motion, seeing the draft manuscript that was presented to the printer, annotated by Newton and Edmond Halley, usually results in a predictable chain-reaction:

(a) excitement (usually manifesting itself as a lift of the corners of the mouth and a spark in the eye)

(b) awe (‘I can touch it?!’)

(c) astonishment (‘it’s in Latin!’)

(d) recognition (‘the equations are quite modern’)

and finally (e) fascination with the structure of Newton’s demonstrations.

The importance of Newton’s work for modern science should not be understated and UNESCO recognised the papers as ‘one of the most important archives of scientific and intellectual work on global phenomena’. But how many scientists and science enthusiasts have actually read or even seen the Principia or his other works? How many can fully understand John Maynard Keynes’s description: ‘Newton was not the first of the age of reason. He was the last of the magicians’? The Newton Papers as well as the Newton Project allow us all to discover some of his works and – we hope – will further entice you to come to the Royal Society to discover our Newtoniana and other Newton treasures in the collections.