Keith Moore highlights the stunning illustrations done by Thomas Landseer - brother of the more famous Edwin - for an account of John Franklin's expedition to the Canadian Arctic.

Have you all been watching the television adaption of The Terror, the fictionalised, final (and fatal) voyage of Sir John Franklin? I kept waiting for the polar bear to turn up, primed by Sir Edwin Landseer’s great painted reflection on the savagery of nature, and humankind, Man proposes, God disposes (1864) with the bears savouring the unfortunate remains of the expedition – only just shy of the genuine horrors undergone by the doomed and hunger-ridden explorers.

Landseer lion, Trafalgar Square

On most days, I pass another of Sir Edwin’s most recognisable pieces of Victorian public art in London, the benign and regal-looking Trafalgar Square lions (don’t climb on the cats, children). Now there were other Landseers with artistic links to felines and to expeditionary science, although all rather eclipsed by the big beast Edwin. Thomas Landseer (1795-1880), his brother and sometimes collaborator, had a nice line in zoological engraving. He was also associated with Franklin, but in happier times, via one of Franklin’s protégées, Sir John Richardson.

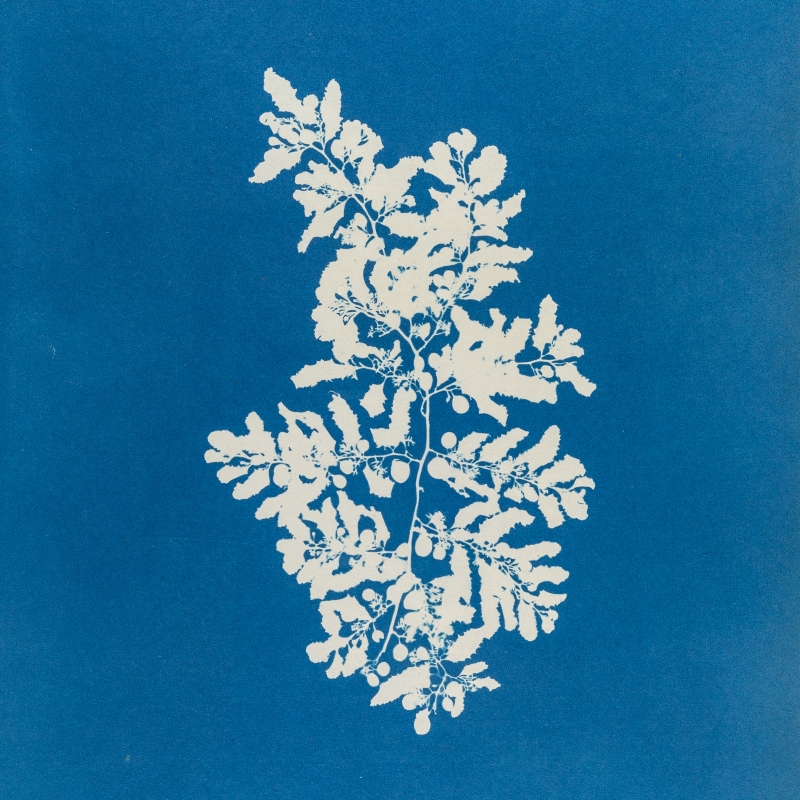

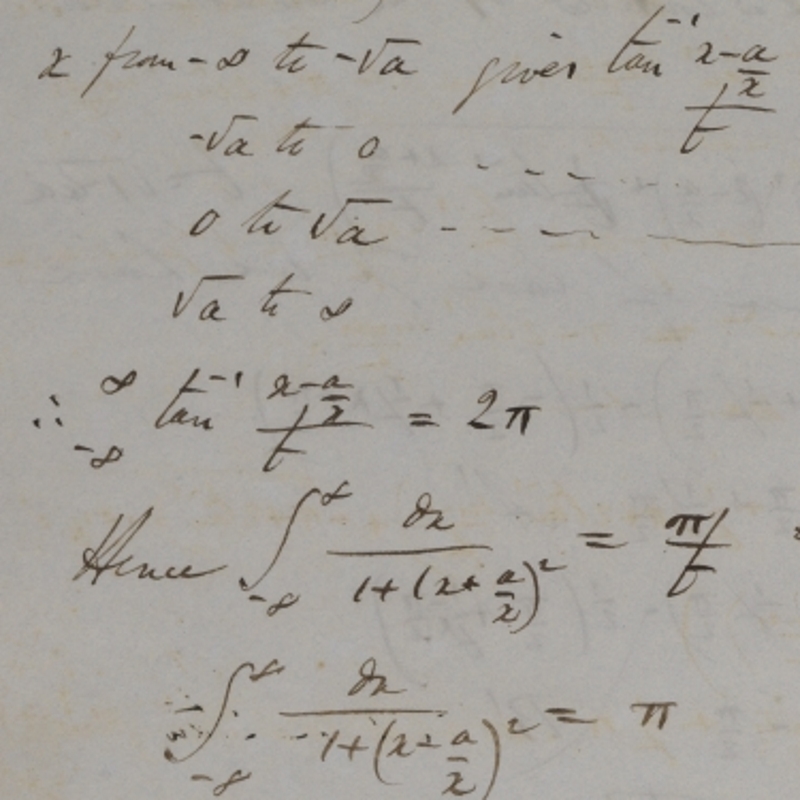

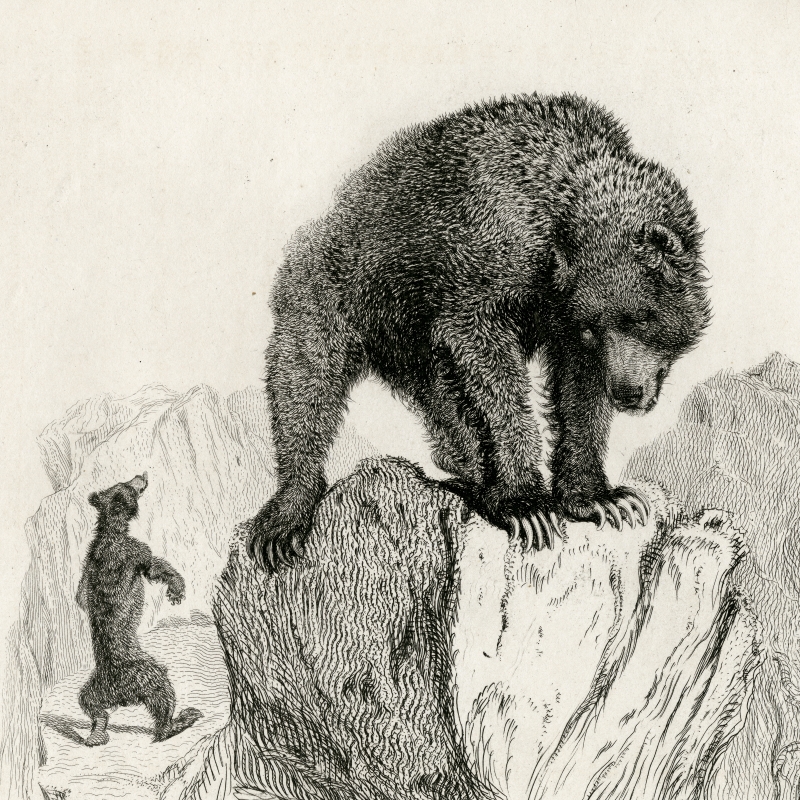

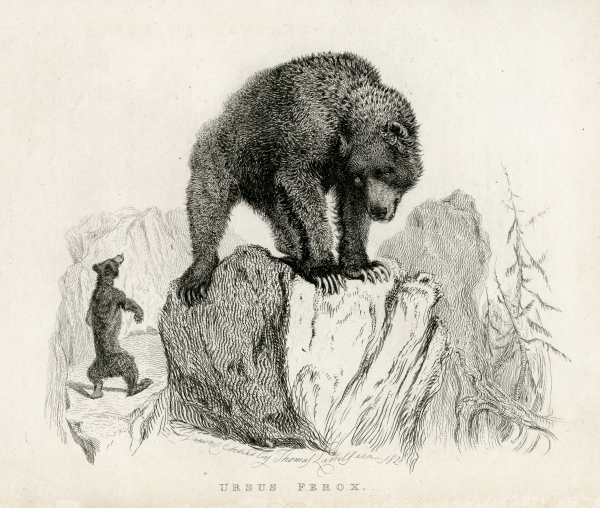

It seems counter-intuitive to have a Royal Navy overland expedition, but that’s what happened in North America in 1825-27, when a party led by Sir John Franklin (1786-1847) and with Richardson (1787-1865) as surgeon and naturalist, scouted the Canadian interior. The zoological findings proved to be too much for a single publication and therefore the work was shared between authors. Richardson completed an account of quadrupeds in 1829 as part of Fauna Boreali-Americana and Thomas Landseer providing some stunningly lifelike etchings – stunning because he was often working from dead specimens preserved in the Zoological Society’s Museum in London. Richardson’s matter-of-fact descriptions of now extinct sub-species, such as the Great Plains wolf or the Hare Indian dog, married to Landseer’s fluid etchings of the animals, as if alive, are a seductive combination.

Grizzly bear by Thomas Landseer, 1829

Nineteenth century London’s natural history museums and menageries were the natural stopping-off point for the capital’s jobbing artists. Thomas Landseer’s Engravings of lions, tigers, panthers, leopards dogs &c. was published in 1853, but contained material from the 1820s and earlier, as he adapted the appearance of animals in the paintings of great artists (including brother Edwin) as a kind of ‘how-to-draw’ manual. For this, and for Richardson’s book, Thomas Landseer used live animals when he could. Big cats, and ‘Martin’, a grizzly bear, were then-residents of the Tower of London’s menagerie. Martin was the first grizzly to be seen in Europe, just as long before, the Tower had housed the first exhibited polar bear.

Personally, I prefer my animals in the wild, or sketched, as they are in John Richardson’s books, and there is one Landseer-like creature I’m curious about. The Royal Society’s Charter Book contains several Royal pages, which successive monarchs have endorsed as patrons of the organisation. Queen Victoria signed the book on 20 June 1838 when a newly-minted page, adorned with her royal coat-of-arms, was submitted to her. But which artist drew the King of the Beasts? I’d love to find out.

Capital lion (and unicorn), from the Royal Society Charter Book, 1838a