A look back at the 1978 ‘Crafts and Elegance’ exhibition at Somerset House, featuring treasures from the collection of the Royal Society.

Next week marks the fortieth anniversary of the opening of the Crafts and Elegance exhibition at Somerset House, which for one month celebrated the completion of a restoration project of the Fine Rooms, the one-time home of the learned societies.

The 25p admission charge afforded visitors a stroll around the redecorated rooms that face the Strand to the north and the great courtyard of Somerset House to the south. On display were the winning entries to the 1978 British Crafts Awards, along with treasures from the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Academy of Arts, and a loan from the Royal Society that included Sir Christopher Wren’s dividers and Sir Isaac Newton’s reflecting telescope.

A bust of Sir Isaac Newton above the entrance to the Fine Rooms at Somerset House, London. Photo © Courtauld Institute of Art and reproduced with permission; supplied to Graham Harrison by Hannah Carr, Courtauld Gallery, July 2018.

During the Society’s 77-year residency at Somerset House, scientific demonstrations and the reading of papers took place beneath stuccoed ceilings and glittering chandeliers. This is where Fellows learnt of the discovery of Uranus by William Herschel, saw Humphry Davy demonstrate his safety lamp and on 31 January 1839 heard William Henry Fox Talbot’s paper Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing. Here Charles Darwin received the Society’s Royal Medal in 1853, as had Talbot in 1838.

Only recently have I grasped the weight of history. Forty years ago, as a young photographer assigned by the Telegraph Sunday Magazine to photograph the Fine Rooms and the precious artefacts belonging to the Royal Society, my task was to produce a set of interesting photographs. The writer assigned to the story was Jim Crace.

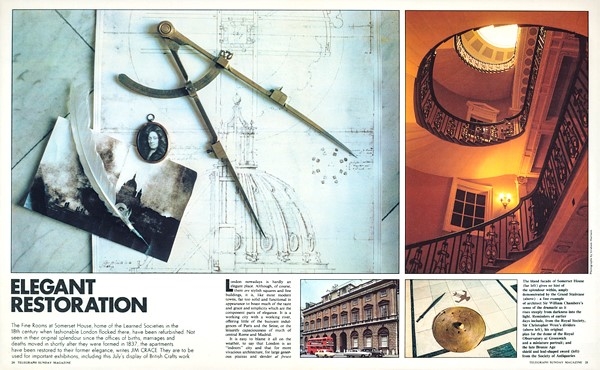

The opening spread for the 1978 Telegraph Sunday Magazine story Elegant Restoration by Jim Crace. Graham Harrison’s photographs include Wren’s dividers, and the Grand Staircase and facade of the Royal Society’s former home, Somerset House.

On the morning of 14 April 1978, on the marble floor at Carlton House Terrace (the Society’s current home), I placed Wren’s dividers on a copy of his plan for the dome of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Beside the dividers, I put a sepia-toned print of Closterman’s 1690 portrait of Wren (trimmed to fit a small oval frame belonging to my mother) then added a photograph of a smoke-shrouded St Paul’s Cathedral and a feather quill borrowed from a pen and ink suppliers in Clerkenwell.

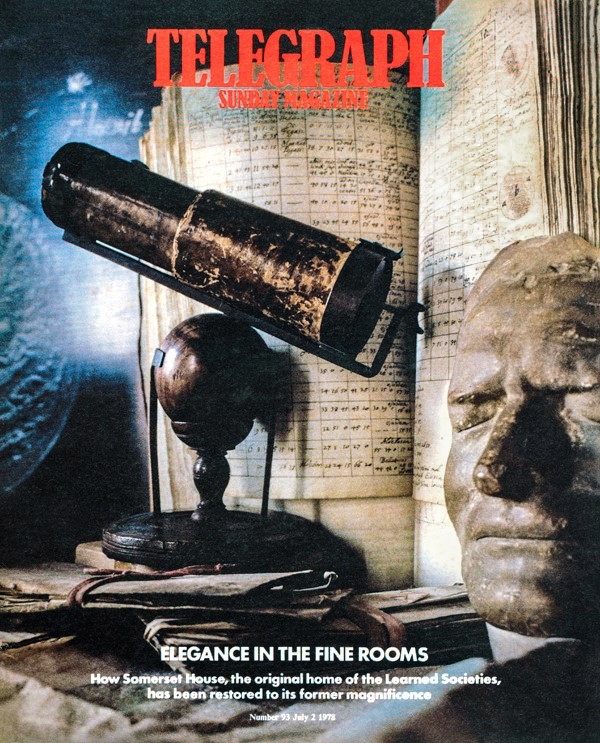

The photograph was taken on a 35mm Olympus OM1 or OM2 camera probably fitted with a standard 50mm lens and lit by a Balcar flash unit. I used the same equipment to photograph Newton’s reflecting telescope at the Society later that day. Newton’s telescope presented a more three-dimensional challenge, and the great man’s death mask became involved in an attempt to add some drama.

Behind the death mask I placed a manuscript guardbook, tentatively identified by the Society’s current Library Manager Rupert Baker as an astronomy or meteorology volume from the Classified Papers series. Behind the guardbook is a blackboard on which I chalked an astronomical diagram, which suggests that I took the photograph in a lecture room.

Newton’s reflecting telescope and death mask at the Royal Society. Cover of the Telegraph Sunday Magazine, 2 July 1978. Photo © Graham Harrison.

Until 2005, when digital technology began to dominate magazine work, transparency film was invariably used for colour images. Transparency film has a superior colour range, density and sharpness to negative film. I opted for Kodak Ektachrome 64 (EPR) for Wren’s dividers and Ektachrome 200 (EPD) for Newton’s telescope – professional films which astronauts in the International Space Station have used to document the Earth from space. Ektachrome finally succumbed to the digital advance in 2012 but, following renewed interest from Hollywood, is set for resurrection later this year.

A meeting of Fellows of the Royal Society at Somerset House, ca.1844. Engraved by Henry Melville after a drawing by Frederick William Fairholt, produced as a plate for London Interiors: a Grand National Exhibition by J. Mead (London, 1844). Image RS.4600 © The Royal Society.

While I tried to create a visual atmosphere, Jim Crace recreated the heyday of Somerset House, when artists and scientists met and debated in adjoining rooms. In his piece published as a cover-story in the Telegraph Sunday Magazine on 2 July 1978 and entitled Elegant Restoration, Crace wrote:

‘One must remove from the present picture rather more than just the patchwork of cars which crowds the courtyard. One must dig away the Victoria Embankment (which was the brainchild of a later generation) and let the marsh margins of the Thames lap the river-facing terrace of the building. One must waft from the Strand the fumes of carbon monoxide and shovel in cartloads of horse dung. One must pluck from the offices those hordes of clerks in their three-piece suits and crêpe-soled shoes and deposit in their place less urgent men in breeches and powdered wigs. Now enter the Fine Rooms…’

Crace has applied his literary talents to the creation of imaginary places in a dozen books since his first novel Continent was published in 1986. Reviewing his latest, The Melody, in The Guardian, Alexandra Harris writes: ‘His readers are kept poised and puzzling, unable to shake off the impression that some clue will give the game away. It won’t. Crace builds his own laboratories, where he is free to bring his elements of interest into new configurations.’

The ‘facts’ relating to the objects I photographed in 1978 have proven equally susceptible to reconfiguration. I’ve since learnt that what was assumed to be ‘the’ Newton death mask is one of several in existence and that his telescope, according to Hall and Simpson’s An Account of the Royal Society’s Newton Telescope (1996), is almost certainly only partly Newton’s handiwork. Even Wren’s dividers are today ‘attributed’ to him rather than being the ones he definitely used in later life.

The Wolfson Room at the Courtauld Gallery in Somerset House. One of the Fine Rooms, this was where the Royal Society met between 1780 and 1857. Photo © Graham Harrison.

What is certain is that after forty years the Fine Rooms in Somerset House are about to undergo major refurbishment once again. The Courtauld Gallery, housed in the Fine Rooms since 1989, closes to the public for two years on 3 September.

This means that you have less than eight weeks to visit what was once the Royal Society meeting room, now hung with the work of Manet, Cézanne and Gauguin. I like to think that the mid- to late-nineteenth century vision of these artists must have been informed and influenced by the scientific breakthroughs – not least Talbot’s invention of photography – announced and debated by Royal Society Fellows decades earlier in the Fine Rooms.