Virginia Mills looks back at the invention of the stereoscope and the rival claims of two Royal Society Fellows, Charles Wheatstone and David Brewster.

Portrait of Charles Wheatstone FRS, by Charles Martin, 1860s

This year marks the anniversary of the invention of the stereoscope. Even if you’re not sure what a stereoscope is, you’ve almost certainly experienced the technology behind this optical device, which allows flat images to be seen in 3D – think of those ‘magic viewers’ or ‘View-Masters’ you probably had as a child. I myself was a particularly jealous guardian of a Disney incarnation that may be familiar to children of the 1990s, though new models continue to be made to this day.

Twentieth-century Disney ‘View-Master’ produced by Fisher Price Inc. 1989-1996.

For millennials born with an iPad in one hand and a virtual reality device in the other, the principles behind the stereoscope are also the foundation of 3D films and virtual reality. Essentially, two images of the same object or scene are presented at slightly different angles, and viewed using either a different lens for each eye or a system of angled mirrors that make the images appear larger and more distant, forcing our suggestible brains into merging the images and interpreting them in three dimensions.

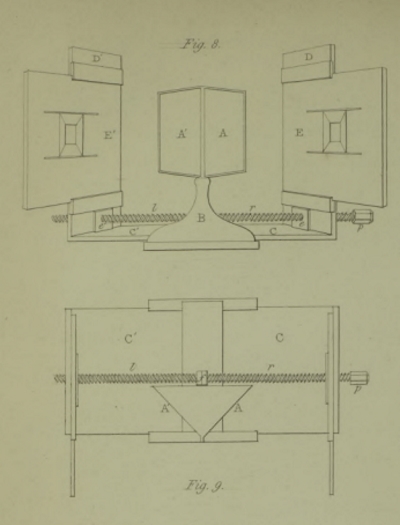

The first stereoscope, designed by Charles Wheatstone and published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society vol. 128 (1838). Image on p.371.

What makes the modern relevance of this invention particularly remarkable is that the stereoscope was invented in 1838, 180 years ago. The man responsible was Charles Wheatstone FRS, who published the first description of his stereoscope in the 1838 volume of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. The title was a snappy one: ‘Contributions to the Physiology of Vision.—Part the First. On some remarkable, and hitherto unobserved, Phenomena of Binocular Vision’.

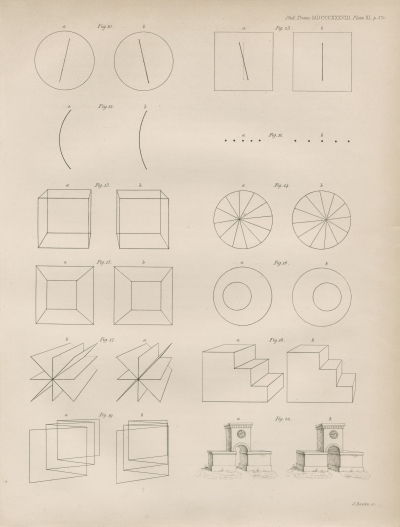

Though designed principally to investigate binocular vision, the stereoscope was sold as a form of drawing-room entertainment. Early purchasers would have had to create their own images to use with the instrument; Wheatstone provided simple line drawings as an example, but explained that it would also work with more complex, artistic renderings:

‘Careful attention would enable an artist to draw and paint the two component pictures, so as to present to the mind of the observer, in the resultant perception, perfect identity with the object represented. Flowers, crystals, busts, vases, instruments of various kinds, might thus be represented so as not to be distinguished by sight from the real objects themselves.’

Line figures from Phil Trans vol. 128 (1838), plate XI, p.372

However, it must have been a tricky endeavour to get the correct perspective to produce good results. So it is an example of the happy confluence of inventions that the development of photography was also being widely explored at this moment: a year after Wheatstone’s paper, William Henry Fox Talbot FRS presented to the Royal Society the first method of reliably fixing a photographic image on paper. He later refined it to enable multiple copies to be produced from a negative, providing the perfect content for the stereoscope for those who, like Talbot, were frustrated by their lack of drawing or painting skills (his cited reason for exploring a method of mechanical reproduction of images). As early as 1840 Wheatstone asked Talbot to take the first pairs of stereoscopic images at Lacock Abbey.

Without the fortuitous advent of more accessible and reproducible photographic methods such as Talbot’s calotype process, the stereoscope may not have been such a commercial success. Unfortunately, with commercial success there often comes a less collaborative face of science: disputed claims of invention. One David Brewster FRS enters the history of the stereoscope with a legitimate claim as the inventor of the first portable 3D viewing device – using prisms rather than mirrors, the lenticular stereoscope was a more compact device than Wheatstone’s, and already bore a strong resemblance to my beloved View-Master in design, minus the Mickey Mouse ears; its ease of use meant that the Brewster Stereoscope gained popularity over Wheatstone’s design. Brewster, however, was also an antagonist in this tale, claiming that Wheatstone had no interest in the use of photographs with the stereoscope and that this was his own innovation. Brewster even went so far as to suggest someone else had a prior claim to the whole concept of the stereoscope, showing little spirit of fellowship amongst these Fellows of the Royal Society.

A more recent designer of stereoscopes is the musician Brian May who, alongside being the guitarist for Queen, is also Director of the London Stereoscopic Company. May has published some of the Stereoscopic images from his own collection of Victorian examples, as well as more recent 3D images (including Queen), and designed a modern plastic viewer to be included with the publications.

Lenticular or ‘Brewster’ stereoscope (creative commons copyright: Museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnologia Leonardo da Vinci, Milan)

There is little doubt, however, that Wheatstone was the true pioneer of stereoscopic devices. Prolific and versatile, the extent of Wheatstone’s vision for his inventions, from commercial uses and public entertainment to military and civil applications, makes him particularly impressive. He is perhaps best remembered for the part he played with William Fothergill Cooke in the invention and improvement of the electric telegraph, installing the first commercial version in the world on the Great Western Railway line from Paddington in 1838. He is commemorated in the name of just one invention, the Wheatstone Bridge for measuring electrical resistance – not, in fact, invented by Wheatstone, who only improved on a design of Samuel Hunter Christie FRS! Some of my personal favourites among Wheatstone’s creations are the ‘Invisible Orchestra’ (a concept, based on a sound-conducting rod, which allowed members of the pre-gramophone public attending Wheatstone’s Musical Museum to marvel at music whilst no musicians were visible), the Kaleidophone (patterns drawn by beads mounted on sound conducting rods), and the first microphone.

Stereoscope anniversary display at King’s College London

3D technology may seem like a modern invention but it has a long history. Even 3D filming techniques have been available to filmmakers for longer than you may think – Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder (1954) was conceived and filmed to be viewed in 3D. Wheatstone and the stereoscope are emblematic of how each generation of scientists builds on the discoveries and inventions of those that have come before, extending and reimagining them for new and improved applications. Recording this history and progression is part of the reason why it is so important for scientists and archivists to preserve the records of scientific endeavour. You can see original manuscripts of Wheatstone’s papers in the archive at the Royal Society, and there is also a small display of stereoscopes at King’s College London, adjacent to the Wheatstone lab – Disney version not included.