The remarkable promises of new cancer drugs often lead to false claims.

The remarkable promises of new cancer drugs often lead to false claims. An Open Biology review looks at the details behind development of the cancer drug ‘hedgehog pathway inhibitor’. Despite initial claims that a quarter of all human cancers would show benefit, only one form of skin cancer and a rare children’s brain tumor showed positive results. Author Tom Curran FRS examines what went wrong to lead to such claims.

Tell us about yourself and your research?

I am the Executive Director and Chief Scientific Officer of the Children’s Research Institute at Children’s Mercy Kansas City. For over forty years, I have worked in various aspects of cancer and neurobiology research. The work of my lab, together with several outstanding collaborators, elucidated the function of FOS and JUN as components of the inducible transcription factor AP-1. We extended these studies to the central nervous system where we pioneered the investigation of inducible gene expression in the mammalian brain and its role in linking short-term, membrane-level stimuli, to long-term changes in neuronal responses through the regulation of gene expression. In 1995, I switched emphasis to focus on children’s brain tumors and I launched a translational research program that developed inhibitors of the Hedgehog pathway for the treatment of pediatric medulloblastoma.

What prompted you to work in this field?

Like many idealistic young scientists, I had entered the realm of biomedical research with the hope that my research would ultimately benefit mankind. I grew up in a working-class village in Scotland steeped in the mining industry. Cancer was a fact of life in the village – the assumption was that you get to a certain age, you develop cancer and you die, badly. Therefore, I was highly motivated to break this vicious cycle. However, because my work was quite basic, even though I was working in the pharmaceutical industry, the time-horizon for impact was quite distant. At the time, my lab was known both for cancer molecular biology and neurobiology research. I very much enjoyed the diversity of the science and the synergy among lab members with complementary expertise. However, initial job opportunities tended to emphasize one or other basic discipline and I was keen to follow my childhood dream to pursue research that was directly relevant to the human condition.

Then, a small hospital in Memphis Tennessee, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, offered me the flexibility to work on anything I wanted while developing a translational research program. I chose to fuse my two areas of interest, cancer and developmental neurobiology, and work on children’s brain tumors. I couldn’t imagine a worse situation for a parent than hearing that their child has a brain tumor. This was a worst-case scenario where any advance would be impactful. Because of our experience in cerebellar development, I chose to focus on pediatric medulloblastoma- a childhood tumor of the cerebellum. Three weeks after making this decision, the first papers appeared linking activating mutations in the Hedgehog pathway to both basal cell carcinoma and medulloblastoma (MB) in Gorlin syndrome. Therefore, we chose to target the HH pathway in pediatric MB with the goal of developing small molecule inhibitors for therapeutic intervention.

Tell us about your review and what are the key messages or findings?

The take home message from the review is that we must all guard against unconscious bias when designing and interpreting experiments. It seems simple, but if you need to use a drug at 100-fold, or even 10,000-fold, above the level required to inhibit its target to achieve inhibition of tumor cell growth, you are fooling yourself. The data are all in the literature and forensic analysis can provide 20/20 hindsight. If your experiment is not working in the standard model, don’t keep tweaking the parameters to “make it work”, as this implies you already know the answer you want. Statistics means that if you perform an experiment on average 20 times, on average one of those will give you a p-value of more than 0.05 – don’t report it!

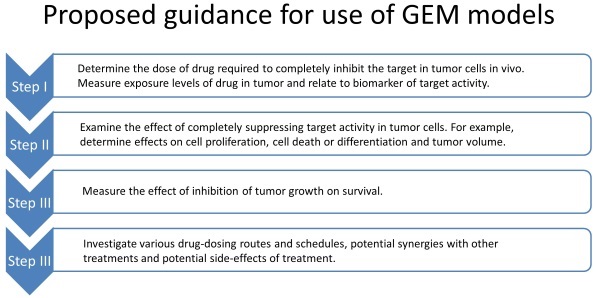

The use of GEM models. Taken from review DOI:10.1098/rsob.180098

Biology is complicated. When cells from HH pathway tumors were propagated in culture investigators assumed their proliferation required HH pathway activity. When the data did not agree with this assumption they maintained the assumption and dumped the data – that is topsy-turvy. The data are the data, as long as the positive and negative controls work. Even if you don’t like the data you still need to dump the assumption. Later investigations revealed that the absence of glial cells in culture removed the source of Shh that was required to maintain HH pathway activity in tumor cells. Thus, none of the hundreds of studies published using HH pathway tumor cell lines are valid. This is a tough lesson, but all of those misleading publications need at least a caveat and most probably they need to be retracted.

What made you submit to Open Biology and tell us about your experience of submitting to the journal?

I had been thinking about this topic for some time and finally decided I would write an article, using my experiences in developing HH pathway inhibitors, to illuminate the root causes of the lack of reproducibility of academic research by industry. Coincidentally, David Glover sent an invitation encouraging Royal Society Fellows to contribute to Open Biology. I felt that the topic was an ideal match for the Open Biology readership, so I made a pitch which David received warmly.

The experience of publishing in Open Biology was quite refreshing. I often regale students and postdocs by dipping into my war chest of publication stories – I won’t give details but suffice it to say that editors, reviewers and copy editors do not fare well. In contrast, the process with Open Biology was supportive, informed, transparent and constructive. Who knew journals could work this way?

Open Biology is looking to publish more high quality research articles in cellular and molecular biology. Find out more about our author benefits and submission process.