When pharmacologist Heinz Otto Schild was interned on the Isle of Man in 1940, the Royal Society was among the organisations working to secure his freedom.

Prior to the Second World War, many German, Italian or Austrian nationals lived and worked in the UK. As the Nazi party rose to power in the 1930s, they were joined by tens of thousands of Jewish refugees and opponents of the regime who fled from Europe. In September 1939 when the War began, over 80,000 of these so-called ‘enemy aliens’ were living in Britain.

This posed a problem for Winston Churchill’s government. Fears that Nazi spies were operating in the country were widespread among the public. Without the manpower to investigate every refugee and foreign national, the decision was taken to round up and imprison all of them.

Many of these prisoners ended up in internment camps on the Isle of Man. The British army commandeered buildings in Douglas, Ramsey, Rushen, and other towns on the island, converting them into detention camps. By August 1940, there were around 14,000 prisoners held on the Isle of Man, and thousands more were transported to internment camps in Canada and as far away as Australia.

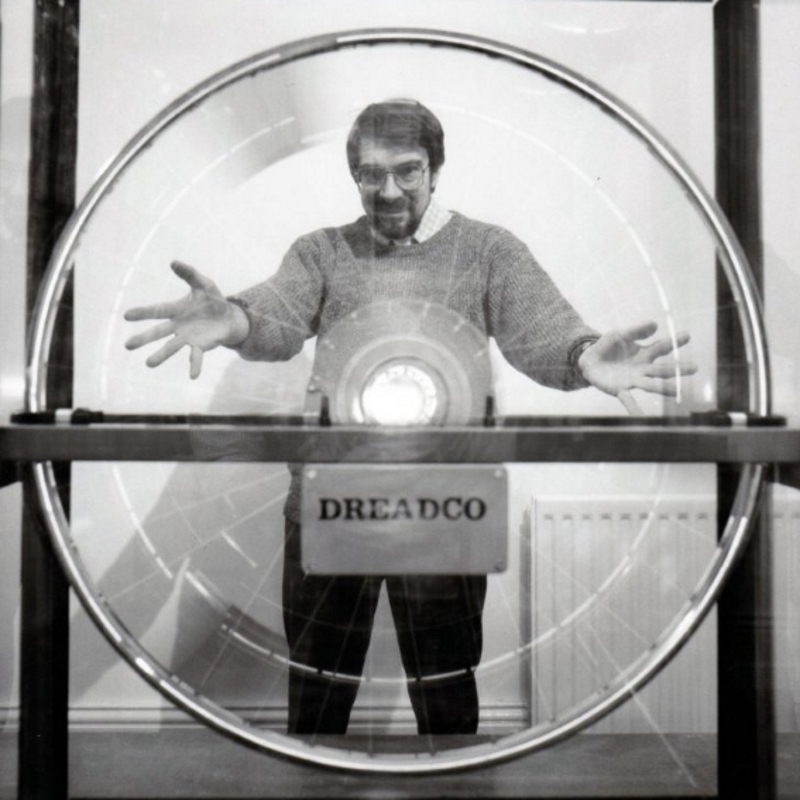

One individual caught up in this was a future Fellow of the Royal Society, Heinz Otto Schild (1906-1984) The Society’s archive includes MS/835, a small collection of correspondence relating to his incarceration, which was donated in 2005.

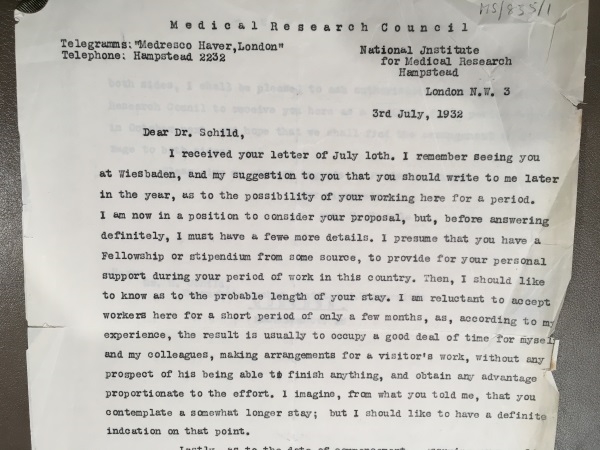

Schild was an Italian national, born to a Jewish family in Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia) in 1906. He studied medicine in Munich and Berlin in the 1920s, and after graduating had the good fortune to meet Sir Henry Dale. Schild raised the possibility of his coming to work in Dale’s laboratory in London, and in July 1932 Dale agreed to the proposal.

Letter from Sir Henry Dale to Dr Schild (MS/835/1)

At Dale’s lab, Schild worked alongside the likes of Wilhelm Feldberg and Sir John Gaddum, and contributed to important research on adrenaline and tissue sample analysis. Schild had only planned to stay in England for a year, but when the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933 he was reluctant to return. Instead, he joined Professor Ivan de Burgh Daly’s new physiology laboratory at Edinburgh University, and proceeded to build a life for himself in Britain.

At Edinburgh he completed his PhD, investigating the link between histamine and anaphylaxis, before taking a role at University College London in 1937. Away from his scientific work, Schild met Mireille Madeline Haquin, a Frenchwoman, while on a walking holiday across the North Downs in 1937. The pair married that same year, and in 1939 they had their first child.

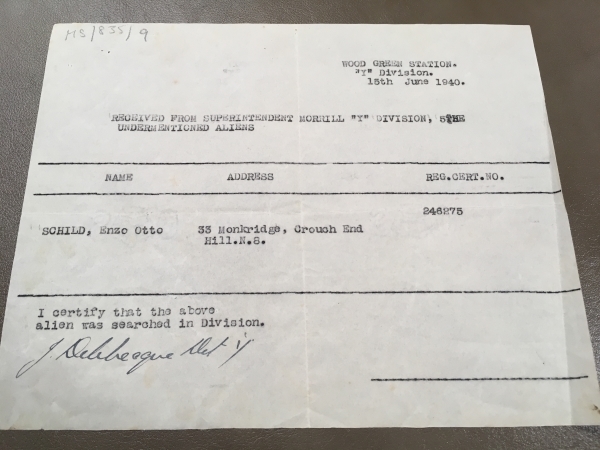

Unfortunately, when the War broke out, he was taken into custody along with tens of thousands of other Italian nationals. 'It is a scandal', Feldberg declared in a letter to Mireille when he learned of Schild’s detention in June 1940. Professor Frank Winton, the head of the Department of Pharmacology where Schild worked, reassured her that her husband had not done anything wrong; 'I imagine he has been fetched not because the police have anything against him but because they do not know much about him'.

Search certificate from Schild’s arrest (MS/835/9)

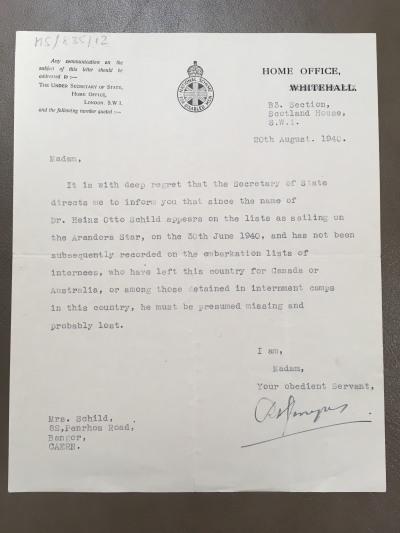

Things must have looked particularly bleak when a telegram from the Home Office arrived in late August, reporting Schild lost at sea after the sinking of the SS Arandora Star. The ship was transporting around 1200 Italian and German prisoners of war to internment camps in Canada. Tragically, during the crossing on 2 July 1940, the ship was sunk by a German U-boat; more than 800 prisoners and crew lost their lives in the disaster.

Home Office letter notifying Schild’s wife of his ‘death’ (MS/835/12)

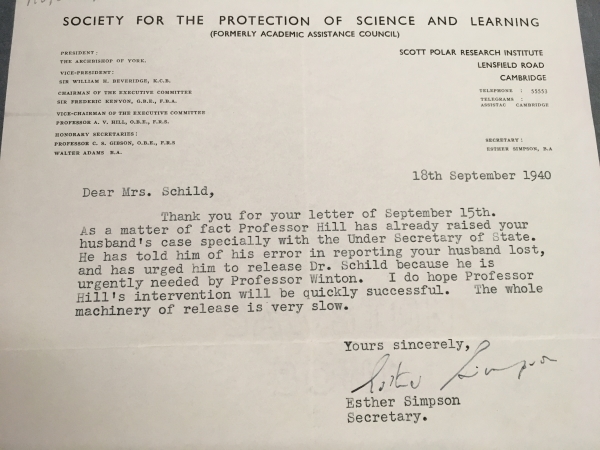

Thankfully, Schild’s wife and friends were soon aware that the Home Office had made a mistake: Schild was alive, and imprisoned at the Palace Camp, the Italian internment camp in Douglas on the Isle of Man. Schild’s friends in the scientific community were busy trying to orchestrate his release. The Home Office received petitions on Schild’s behalf from the Royal Society, University College London, and the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL), now known as the Council for At-Risk Academics.

Letter from Esther Simpson, Secretary of the SPSL, to Mrs Schild (MS/835/14)

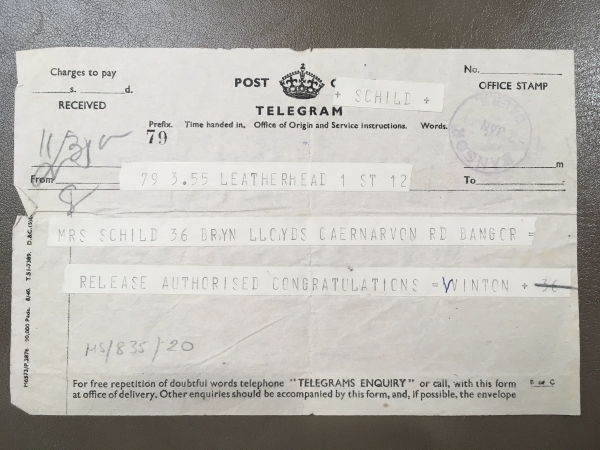

In the meantime, however, Schild had applied to join the Pioneers, an engineering corps in the British Army where foreign nationals from enemy countries could serve. Thousands of German, Italian and Austrian nationals chose to join the Pioneers and assist in the war effort rather than remain in the internment camps. Luckily, at the beginning of January 1941 the appeals for Schild’s release were finally successful, and he wasn’t sent to the front line. A.V. Hill, the secretary of the Royal Society at the time, wrote to Mrs Schild with news that 'instructions have been given for your husband’s release. I am very glad about it. The delay is almost a record.'

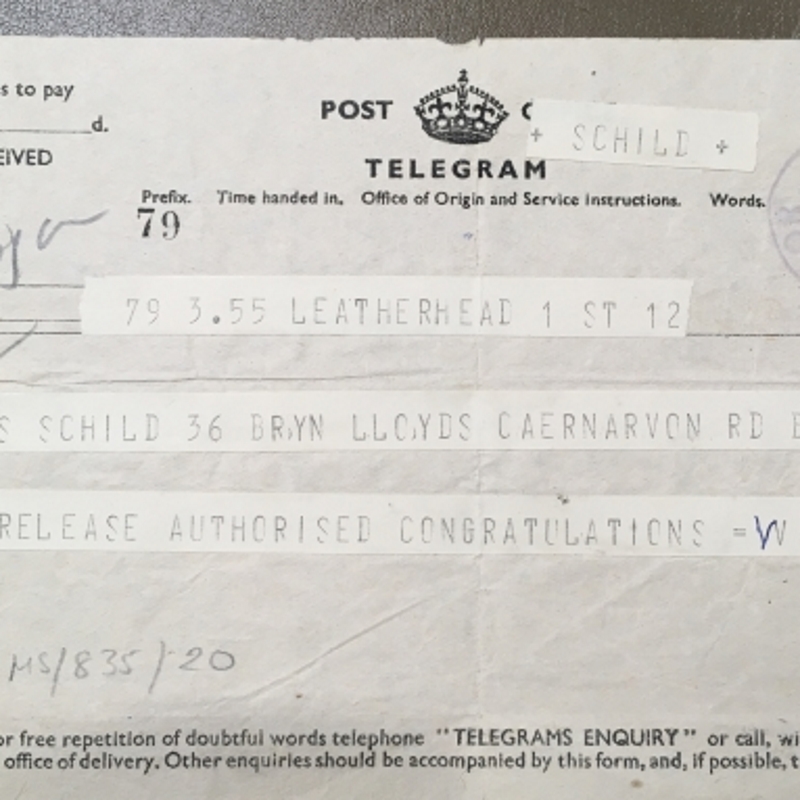

Telegram from Professor Frank Winton to Mrs Schild with congratulations on the release of Dr Schild from his internment camp (MS/835/20)

Many more imprisoned foreign nationals were released throughout 1941, though the camps on the Isle of Man remained operational until the end of the War. Schild’s own experiences did not dissuade him from staying in England, and he returned to work at University College after his release. He also gained British Citizenship in 1948, with scientists including Dale providing character references for his application; just as in 1940, the scientific community in Britain was more than happy to lend a hand to a fellow scientist in need.