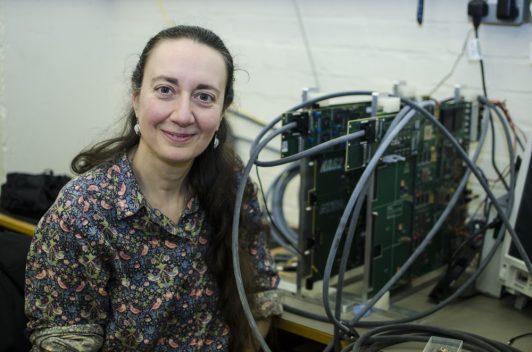

To celebrate Peer Review Week we talked to the University of Birmingham's Professor Cristina Lazzeroni.

Tell us about your area of research

My research field is elementary particle physics. I am an experimentalist, and combine work on detector and electronics with data analysis. In particular, some years ago I contributed to studies related to matter-antimatter asymmetry, as well as the discovery of the related so-called “direct CP violation”. At present, I lead the UK effort in the NA62 experiment at CERN, trying to find new physics phenomena in rare processes involving the strange quark.

How did you first become involved in the Equality and Diversity Committee at the University of Birmingham?

I was asked to join the Committee for the Physics Department at the time of our first applications to ED awards (such as Juno and Athena SWAN). My initial role was to help collect and analyse data regarding ED in the School, but I found it so interesting that I joined the Committee for good. I was later asked to step up as Chair of the Committee, and have led the most recent departmental applications for ED awards this year.

What does your role as Chair of the Committee involve?

I organise the ED work in the School of Physics and Astronomy. This requires working with both the Head of the Department and the Head of Groups, and involves discussing current news and issues; planning possible strategies to investigate and then using these to mitigate ED issues; and finding new ways to improve the ED-related aspects of departmental life.

I also lead the collection of data and analysis of evidence related to ED aspects in the department, and as a consequence, I get to make recommendations on what to change or improve. I also liaise with other similar committees throughout the University, such as the ED Committee for the College of Engineering and Physical Sciences.

What has your collection of data and analysis of the evidence shown you?

One example, is that we realised that clearly advertising the possibility of flexible working really helps staff to consider this option more seriously. Since then, a number of staff have benefitted from the flexible working scheme.

Why do you think diversity is important?

One point about being living entities is that we are all “different” from each other, and it is clear that “normality” has been given too much emphasis. Diversity is the norm.

My research is often part of big collaborations, and there you can really appreciate that diversity is the key to success. Having people with different skills, personalities, different approaches to problems and so on, is a real strength. To me, ED means flexibility of thinking and always keeping an open mind. It is no surprise that I am a strong advocate of team work.

In 2015, the Institute of Physics documented that only 25% of all physics doctoral students in the UK are women. Do you have any thoughts as to why women may not be entering the field?

This is indeed the case in my institution as well. This is of course a complex subject, however we consulted our undergraduates and realised that it would help to improve both the adverts and the application processes at the university to make both more ED friendly. This is what we plan to focus on next.

As a woman in particle research, what has your experience been like in a male-dominated field?

I studied in Italy as an undergraduate and PhD student, and there are many more women in particle physics in Italy than in the UK. But indeed, not many women study physics in Italy at school to start with. So while I felt a lot less isolated in Italy than female PhD students feel here in the UK, I still felt like a minority. What I do remember however, is that we were really proud to belong to that minority.

Despite my pride, I do also remember being terrified of showing my work initially, and compensating my uneasiness in meetings with an artificial outgoing attitude. Looking back, I think women who have a career in physics are self-selected for extra asserting power and determination.

Your work involves a lot of peer review for grant applications. Can you tell us a bit about your experiences in this area?

I am involved in a lot of peer review for grant applications. While career breaks are taken into account, or at least there are specified means to do that, one other parameter is relevant and often overlooked: the history of location of employment.

Often, candidates are praised if they have moved to a number of good institutions in their career, but what about excellent applicants with a family or relations that prevent them from moving as much as others? These candidates don’t have a career break to declare, and couldn’t/wouldn’t declare their reluctance to move around – for that, they could be discriminated.

I have seen excellent PhD students who decided not to pursue research jobs because this implies moving around too much, in a way often incompatible with having a family. I have also seen grant reviewers noting that the PI employment history isn’t ideal because it’s limited to a couple of (although good) institutions. While this could indicate a limited scope of the research performed by the researcher, it could also simply be discrimination.

Based on your experience, is there any piece of advice you would pass on to other institutions who wish to increase diversity in STEM?

Every institution is different, and I would recommend first of all to make a careful investigation of the areas that would benefit most from improvement. Then I would suggest to always consult those directly concerned – often they have the best insight about how things could be improved.