Today marks the launch of a new initiative in which the Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience section of Royal Society Open Science guarantees to publish any close replication of any article published in our journal, and from most other major journals too.

Today marks the launch of a new initiative in which the Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience section of Royal Society Open Science guarantees to publish any close replication of any article published in our journal, and from most other major journals too.

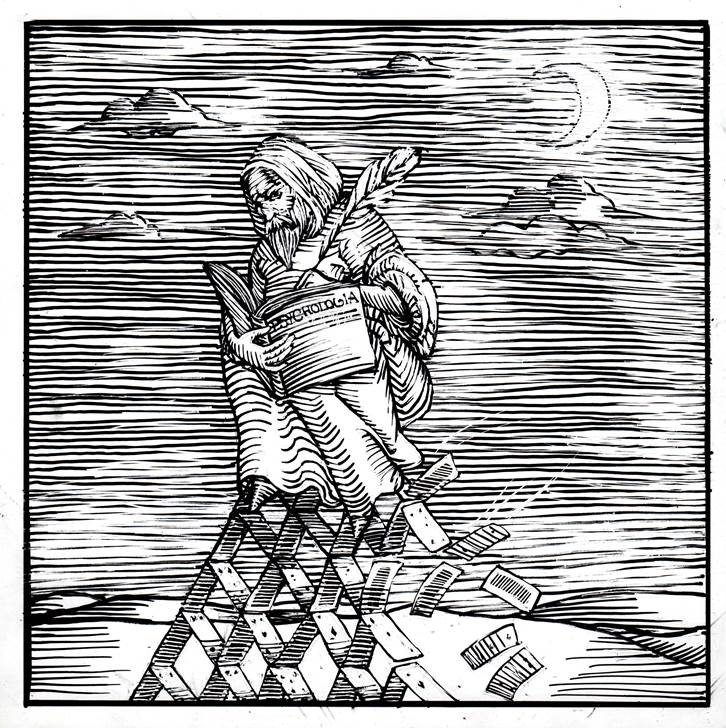

Replication – it’s the quiet achiever of science, making sure previous findings stand the test of time. If the scientific process were a steam ship, innovation would be sipping cognac in the captain’s chair while replication is down in the furnaces shoveling coal and maintaining the turbines. Innovation gets all the glory but without replication the ship is going nowhere.

In the social and life sciences, especially, replication is terminally neglected. A retrospective analysis of over a hundred years of published articles in psychology estimated that just 1 in 1000 reported a close replication by independent researchers.

What explains this unhappy state of affairs? In a word, incentives. Researchers have little reason to conduct replication studies within fields that place a premium on novelty and innovation. Also, because psychology and neuroscience are endemically underpowered, a high quality replication study usually requires a substantially larger sample size than the original work, calling on a much greater resource investment from the researchers.

Even if researchers summon the necessary motivation and resources to conduct a replication, getting their completed studies published can be a thankless and frustrating task. Many journal editors – especially those who prize novelty – will desk-reject replication studies without them ever seeing an expert reviewer. And those replications that go further face a grueling journey through traditional peer review. Where the replication study fails to reproduce the original findings, proponents of the original work will point to some difference in methods, however trivial, as the cause for the non-replication. And where the replication succeeds, the reviewers and editor are likely to conclude that “we knew this already, so what does the study add”? All paths veer toward the same destination: rejection and the file drawer.

At Royal Society Open Science we believe that overcoming problems with reproducibility in science requires the creation of a new path that recognises and truly values the importance of replication.

Why Registered Reports are not (quite) the answer

Those familiar with the range of reproducibility initiatives currently available in science will be wondering if Registered Reports, which are already offered at Royal Society Open Science, solve the problem of championing replications. While they move us in the right direction, they don’t go far enough.

With Registered Reports, the protocol underlying a study is reviewed before starting data collection or analysis, and the paper is accepted in advance regardless of the eventual results.

This format presents two main weaknesses. First, a replication study submitted through the Registered Reports track can be rejected before results are known, if the reviewers believe the original study contained a significant flaw or oversight, or if the question itself is judged uninteresting or unimportant. This can incentivize authors to change the proposed design, moving it away being a close replication. This invalidates the whole enterprise.

Secondly, Registered Reports are suitable only for proposals where the results are not yet known by the authors. This means Registered Reports can’t unlock the file drawer of existing replications that are already completed and analysed.

Introducing accountable Replications

We agree with Sanjay Srivastava, creator of the Pottery Barn rule of scientific publishing: “you publish it, you buy it”. In his words: “Once a journal has published a study, it becomes responsible for publishing direct replications of that study. Publication is subject to editorial review of technical merit but is not dependent on outcome.” When a journal publishes an empirical study it becomes accountable for the replicability of that study.

How will this policy work in practice? Readers can find our detailed editorial policy for Replications but the main highlights are:

- Royal Society Open Science guarantees to publish any close replication of any study previously published in its Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience section. This commitment extends to replication studies themselves, with no limit on the number of acceptable repeats.

- For already-completed studies, authors can submit via the Results-Blind track in which the introduction and methods are initially reviewed with the results withheld, and with the editorial decision based on this initial stage of review regardless of the results. For prospective proposals, authors instead submit the introduction and methods via the Fully Preregistered track (our existing Registered Reports workflow with slightly different review criteria).

- One concern with results-blind review (where results are known to the authors but not the reviewers) is that reviewers may assume that the results are negative or confusing, leading to biased reasoning when assessing the paper. Therefore, reviewers will initially be blinded to whether the article has been submitted via the Results-Blind or Fully Preregistered track. Submissions in both categories will be written in past tense.

- To achieve acceptance, the study must be sufficiently close to the original work to be considered by expert reviewers to be a replication. It must also have a sufficient sample size, and it must be ethically approved.

- We are assuming accountability for a range of other major journals that publish research in psychology and cognitive neuroscience (see our detailed policy for the full list). We will also consider, on a case-by-case basis, presubmission enquiries for replications of studies published in a wider range of journals.

- If there is a flaw in the original study, then depending on the severity of the flaw, an editorial commentary may be appended to the final article noting the methodological limitation. Crucially – and uniquely to this initiative – unless the study being replicated contains a severe flaw AND arises from a paper published somewhere other than Royal Society Open Science, the existence of this flaw will not influence the publication decision. And even then, the flaw will not lead to outright rejection but the requirement to conduct an additional corrected follow-up study by the replicating authors.

Where will this policy take us?

In the short term we hope to see it unlock the vast file drawer of unpublished replications in psychology and cognitive neuroscience.

In the long term, our vision is broader. As Sanjay Srivastava pointed out over five years ago, we must realign the incentives in publishing to make journals accountable for the reproducibility of the work they disseminate. If a journal achieves fame for publishing a large quantity of impactful, novel studies with positive results, but is then bound to publishing attempted replications of those studies, then the journal has a reputational incentive to ensure that the original work is as robust as possible.

We hope to see this model normalise replication studies and give the scientists who conduct them the prominence they deserve. Replication has spent long enough shoveling coal in obscurity. It’s time for a taste of the captain’s chair.

Image credit

Credit: Anastasiya Tarasenko