How did a bronze maquette of the British Library's iconic Newton statue come to be in the Royal Society's collections? Ellen Embleton uncovers the story.

Hailing from Edinburgh, I’ve always been a big fan of sculptor and artist Sir Eduardo Luigi Paolozzi (1924-2005). Born and raised in Leith, and later a student of Edinburgh College of Art, Paolozzi left the Scottish capital peppered with his iconic bronze sculptures. When I first moved to London I delighted in Paolozzi-hunting around the city, with his Head of Invention and, of course, his Newton after Blake soon joining my list of favourites.

Head of Invention outside the Design Museum; Newton after Blake outside the British Library (both images from Wikimedia Commons)

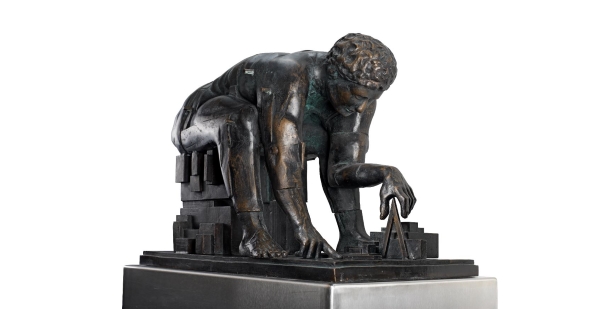

To my shame, it was only very recently that I realised we have our very own Newton after Blake here at the Royal Society. Not quite at the same scale as the one outside the British Library, this bronze maquette stands at 41cm high and is located amidst the staff offices on the second floor (in my defence, I work on the third floor). I thought I’d indulge my interest in the artist with a blog post that delves a little further into this sculpture’s story and influences.

Paolozzi’s gift to the Royal Society, Newton after Blake, on a metal plinth, 1995 (S/0027)

As noted in our Council Minutes, Paolozzi gifted the maquette to the Society in 1995, two years prior to the unveiling of the full-size sculpture outside the British Library. While Paolozzi’s interaction with the Society was somewhat brief – other than the maquette, I managed to track down only one other trace of him in our collections (see photograph below) – themes of science and technology appear time and again in his work, informing, among other things, his depictions of the human body.

This is partly owing to his involvement in the Independent Group, which met at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in the 1950s. They discussed topics which they felt were otherwise ignored in the art world, principally science, technology and popular culture. In 1951, group members held an exhibition on the subject of morphogenesis called Growth and Form, based on the work of another of our Fellows, biomathematician D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Clearly, Newton was not the only Royal Society Fellow to inspire Paolozzi.

Eduardo Paolozzi with Sir Michael Atiyah PRS at the 1995 New Frontiers Soirée

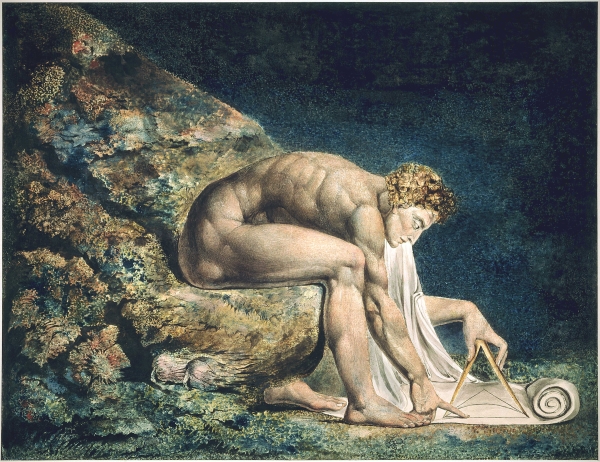

These sympathies for science are perhaps what led Paolozzi to a print of Isaac Newton by William Blake (1757-1827), which became the inspiration for his sculpture. In Blake’s rendition, Newton sits on a rock, completely absorbed in his work and apparently oblivious to the colour and beauty of his surroundings:

William Blake’s Newton, 1795 (image from Wikimedia Commons)

Blake’s Newton, depicted as hunched, naked and muscular, bears little resemblance to the man himself. One senses that Blake did not set out to create a true likeness, but rather to portray an idea of Newton, with no attempt to deny that his attitude towards Newton was entirely uncomplimentary. This particular print seems to scoff at Newton’s scientific thinking at the expense of the natural beauty that surrounds him, while other works by Blake, including the poem You don’t believe and The book of Urizen, also denounce the great mathematician’s rationality and reason.

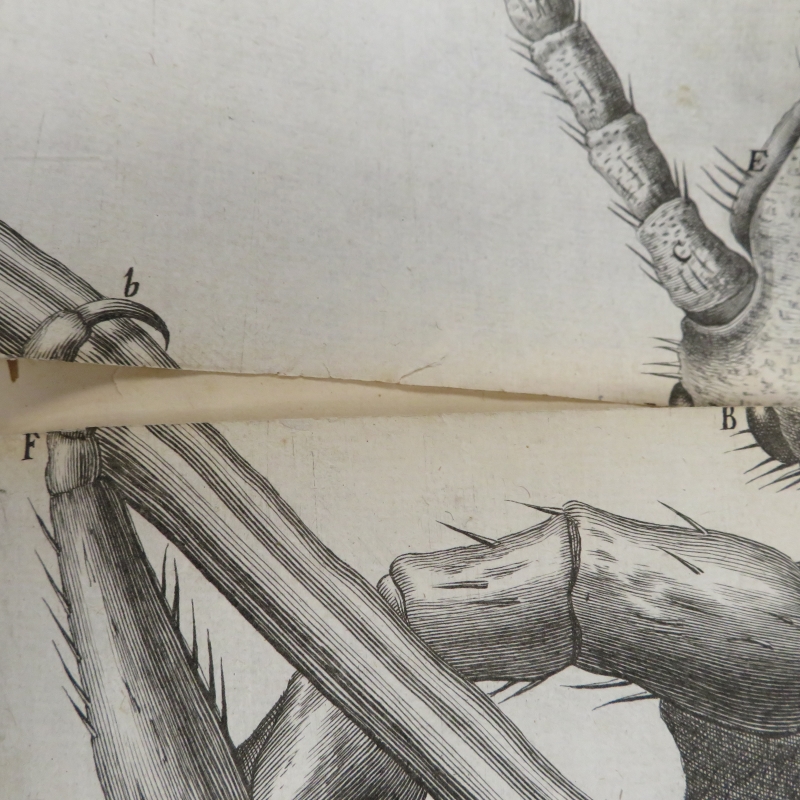

Engraving of William Blake by Italian engraver Luigi Schiavonetti, 1801 (IM/000403)

Paolozzi’s interpretation of Blake’s print adapts Newton in many ways. In both his full-size sculpture and our maquette, Newton is depicted as sitting on geometric blocks, rather than a rock, with a mechanised body seemingly held together by bolts at its joints. In removing the associations of nature and beauty present in Blake’s print, Paolozzi leaves us with a scene of concentration and dedication only, free from any hints of judgement or critique.

Newton after Blake, 1995 (S/0027)

Indeed, Paolozzi’s remake of this eighteenth-century image does not come across as a satire of either Newton or Blake. Rather, it seems to be an attempt to unite these two historical figures and provide a link between the highest ideals of science and of art. As someone who works with the many, often-unexpected connections between these two realms, the maquette strikes me as a beautiful representation of this overlapping relationship, and a piece very much at home within our sculpture collection.