The Royal Society has been asking for expert advice on papers submitted for publication since the 1830s, and quality (or something like it) has always been one of the elements under consideration.

Peer review is widely seen as playing a critical role in ensuring the quality of published research. The Royal Society has been asking for expert advice on papers submitted for publication since the 1830s, and quality (or something like it) has always been one of the elements under consideration. Here, Professor Aileen Fyfe from the School of History at the University of St Andrews, charts the journey of peer review, and explains how the definition of ‘quality in peer review’ has changed over time.

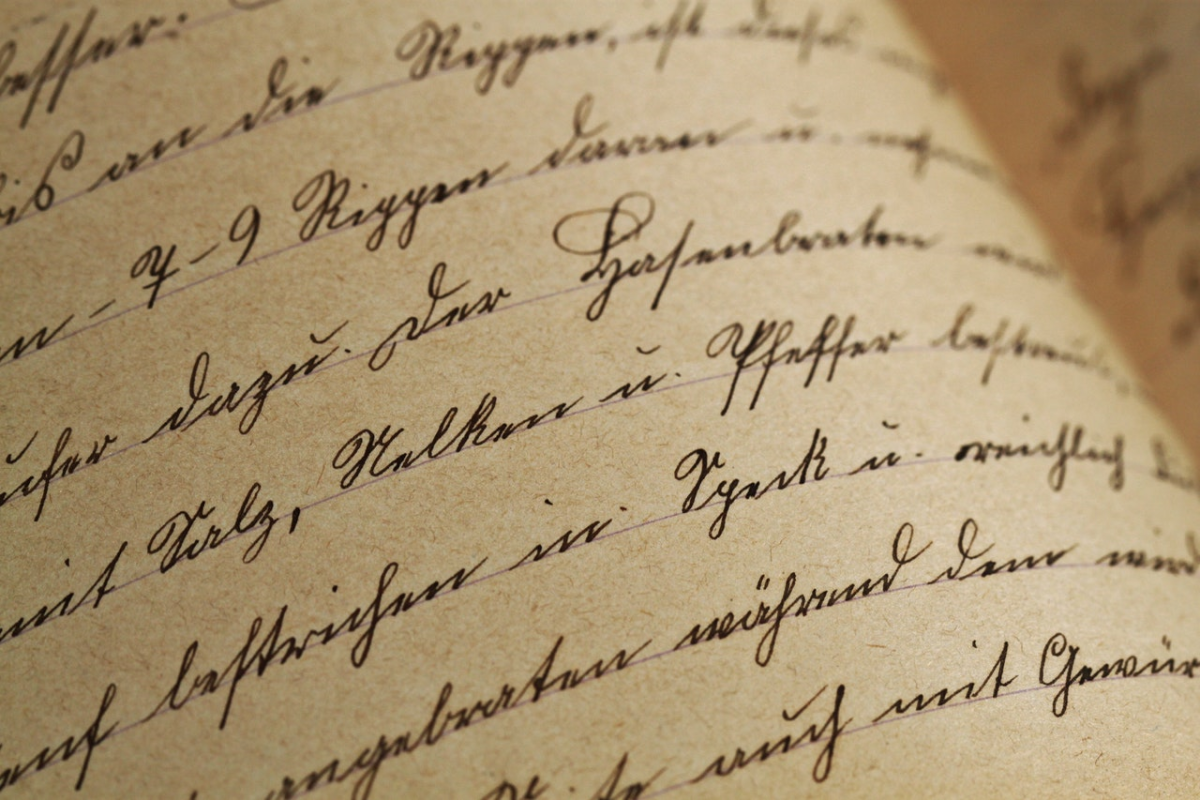

1800s – from invitation and instinct to printed report form

1800s – from invitation and instinct to printed report form

The typical invitation to referees in the mid-nineteenth century made no effort to lay down evaluation criteria, simply taking it for granted that the sort of people being asked to referee would know what a publishable paper would look like. In 1832, the Society’s President had described the ideal referee as someone who was able ‘to establish at once the full importance of a discovery, to fix its relations to the existing mass of knowledge, and to define its probable effect upon the future progress of science’. (In 1832, only members of the Society’s Council, ie well-established men of science, were asked to referee; but very soon, any Fellow of the Society might be asked.)

In the late 1890s, the standard invitation letter to referees was supplemented by a printed report form. Together, these documents offered some guidance to referees about what (but not how) to evaluate. Referees were told that papers for the Society’s Philosophical Transactions should ‘mark a distinct step in the advancement of Natural Knowledge’. How big a step needed to be, to count as ‘distinct’, was left to the referee’s conscience.

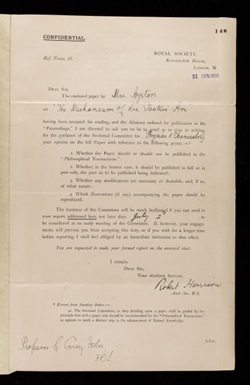

1900s – outstanding interest and topicality, not routine research and results

By the 1930s, the Royal Society’s editorial office was inundated with submissions, and the UCL mathematician Louis Filon argued that it should stop publishing ‘what may be termed routine research… [that] deals with observations and results of secondary importance’. He drafted revisions to the report form and guidance asking referees to consider whether the ‘contributions to knowledge’ were of ‘sufficient scientific interest for the space required’; and insisted that the Society’s journals were ‘not the proper medium for the accumulation of data or the elaboration of minor details’, but should be reserved for results or methods ‘of critical importance’.

By setting up an opposition to ‘minor details’ and ‘accumulation of data’, Filon sought to help referees understand what ‘critical importance’ might mean. And where the report form had once asked for ‘general remarks’, it now asked for suggestions to ‘enable the author to improve or correct’ his paper. By the 1990s, referees were being asked to grade papers as being ‘of outstanding interest and topicality’; a ‘good paper, worth publishing’; or ‘a worthwhile paper, which should be published if space permits’. Once more, the desired quality was being defined in contrast to the more mundane.

Today – stipulations, subjectivity and slippery concepts

The criteria issued to referees have also become increasingly explicit about what aspects of a paper should be taken into account. For instance, the Royal Society now asks its referees to pay attention to writing style, ethics and the appropriateness of research methods, as well as originality, length, illustrations, and ‘importance’.

But how an individual referee evaluates each of those features remains subjective. In the twenty-first century, referees are a far more diverse group than they were in the early days of Royal Society refereeing, which makes it more difficult to rely on implicit shared understandings (even if one wanted to: consider implicit bias…). The Society’s current guidelines look for ‘outstanding scientific excellence’. But such terms as ‘excellence’, ‘outstanding interest’ and ‘critical importance’ remain slippery concepts, very much dependent on the eye of the beholder.

Royal Society authors benefit from rigorous peer review by practising scientists in relevant disciplines, and many of them tell us how their paper has been improved as a result. Experience our high quality, constructive peer review for yourself by submitting to one of our journals.

Images

1 – Report form 1800s

2 – Report form and guidance 1900s – this 1957 report is based on Filon’s revisions.