Explore the Society’s correspondence from the 1920s, which charts the period in Spring 1925 when the Royal Society held a book sale of over 200 volumes from the Arundel Library.

One of the perks of cataloguing a collection like the Royal Society’s is that you can follow items, and their stories, over many lifetimes. I found this when I started work on New Letter Books 67 and 68. They contain the Society’s administrative correspondence from the 1920s, and chart the period in Spring 1925 when the Royal Society held a book sale of over 200 volumes from the Arundel Library.

The story of this library asks us to skip back to the early 1600s, before the Royal Society had formed. It starts with Thomas Howard, 14th Earl of Arundel. Known as ‘the Collector Earl’, he had a huge penchant for – you guessed it – collecting. When it came to art, antiques, and books, the quality and quantity of stuff amassed by Arundel and his wife Alethea Talbot, on their travels and at home, rivalled even King Charles I’s collection. The expansive library was known as the Arundel or Norfolk Library (the Earl of Arundel was also, confusingly, the Duke of Norfolk), and was much beloved by its bibliophile owner.

Arundel’s collection was partly a passion project, and partly a way of recouping his losses after a series of disasters in the history of this Catholic family: his grandfather had been beheaded for treason, and his father had died in the Tower of London, stripped of titles and lands. The collection was meant to be kept together as an enduring monument to the family – but Arundel didn’t bargain for the temperament of his own descendants. And here’s where the Royal Society steps in.

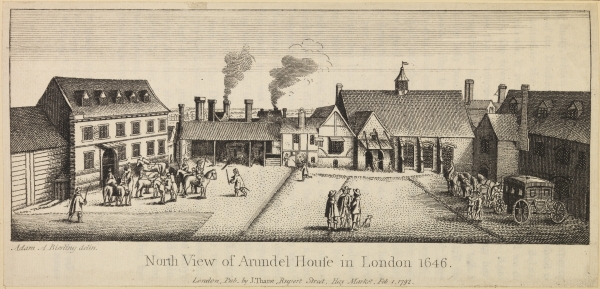

North view of Arundel House, by Adam Bierling after Wenceslaus Hollar’s 1646 original. Published by J Thane, London, 1792

The Arundel Library was eventually inherited by the Collector Earl’s grandson, Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk. Howard was well-connected with the key players of the early Royal Society, including Samuel Pepys and Henry Oldenburg. When the Great Fire of London disturbed the Royal Society’s normal meetings at Gresham College, Howard offered up Arundel House as an alternative. Soon enough he began to make donations from the family collection, such as an Egyptian mummy, described with forensic detail in Nehemiah Grew’s catalogue of the Repository, this blog’s namesake. The library ultimately followed.

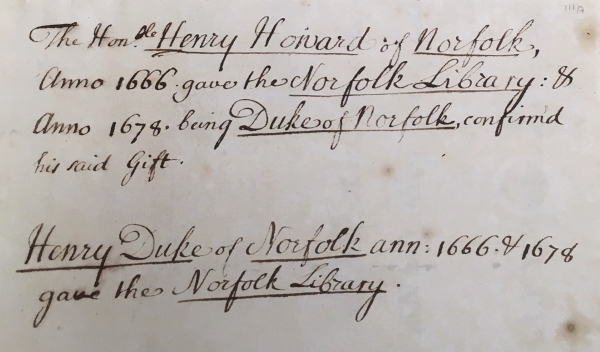

Extract from ‘benefactors’ list’ RS DM/5/113A

It was John Evelyn FRS who actually persuaded Henry Howard to bequeath the Norfolk Library, or Bibliotheca Norfolciana, to the Royal Society. Evelyn paints a rather disparaging picture of Howard as a ‘negligent’ book owner, with ‘so little inclination to books that it [the bequest] was the preservation of them from embezzlement’. This nugget – hardly a sterling recommendation – comes from Evelyn’s diary, which you should read alongside Samuel Pepys’s for optimal early Royal Society gossip. In our archives, we have a written catalogue of the books given in this original bequest (Cl.P/17/33) – or, and much easier to read, there’s a printed catalogue of the Bibliotheca Norfolciana from 1681.

Fast forward to the 1920s, and the Royal Society had moved house – and its library collection – many times. Lack of space was always a pressing issue. The book sale was arranged partly because the library at Burlington House, the Royal Society’s home at the time, was overfull. However, the New Letter Books suggest that the lack of space brought another issue into sharp relief: the question of what, exactly, constitutes a scientific book fit for a scientific library. Francis Towle, Assistant Secretary and Librarian at the time, makes it clear in his letters that the Royal Society was only interested in collecting ‘strictly scientific’ works. But that definition isn’t so clear-cut when dealing with early modern books. Topics that were relevant to the study of ‘improving natural knowledge’ in 1660 had gone out of vogue by 1925. Alchemy, anyone?

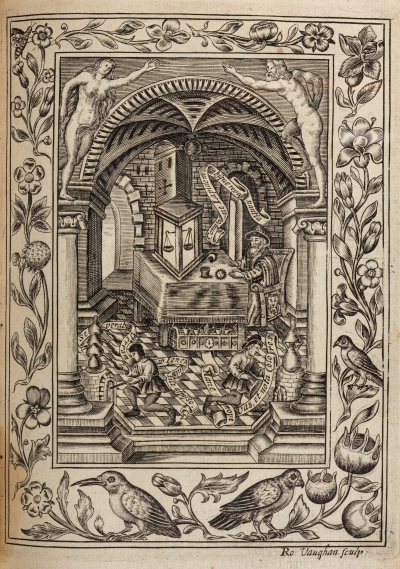

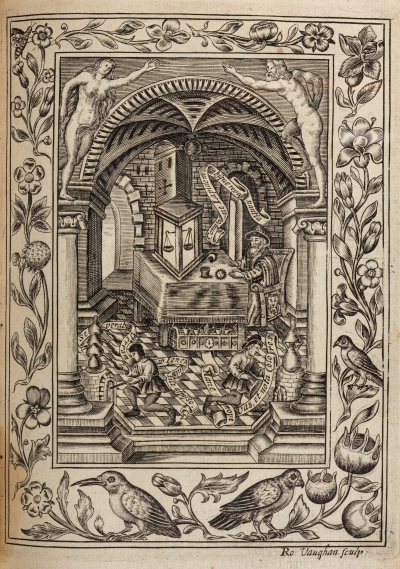

Alchemy in Elias Ashmole’s book of poetry Theatrum chemicum Britannicum (1652)

So the books were sold, and moreover, at a public auction. The Times criticised the Royal Society harshly for allowing this. They hadn’t had one previously; in the last big book sale of 1831, items from the Arundel collection were sold exclusively to the British Museum. Sales then had included a brilliant codex of Leonardo da Vinci’s papers, now in the British Library. The main complaint of The Times was that, unlike in 1831, there was no guarantee that books like this would stay in Britain, or in the public domain, where they ‘are of no small educational value as works of art and of historic interest’. Luckily, the drive towards digitisation means that you can now access a lot of these books in one form or another.

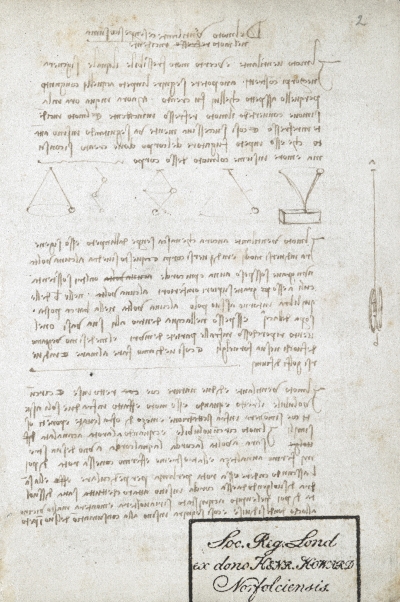

The Codex Arundel, Da Vinci’s notebook now in the British Library. It shows his characteristic mirror writing and bears the Royal Society’s Norfolk Library stamp

Though they might be scattered, we can still trace Arundel’s books through the archives. A handy resource for getting a sense of the collection is a scrapbook compiled by Royal Society staff in the 1920s (PC/7/1). Along with a timeline of everything that had happened to the Norfolk Library since the 1660s, it contains the original Sotheby’s catalogue of the sale, annotated with prices. There are so many items in this catalogue that I was spoilt for choice when writing this blog. You can only imagine a wealthy book-buyer’s delight in 1925! I could easily wax lyrical about the Hebrew psalm book from the fifteenth century, Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales as printed by Caxton on the first printing press in England, the second folio of Shakespeare’s works, or the first translation of the Bible into the Algonquian Massachusett language, Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God (1663).

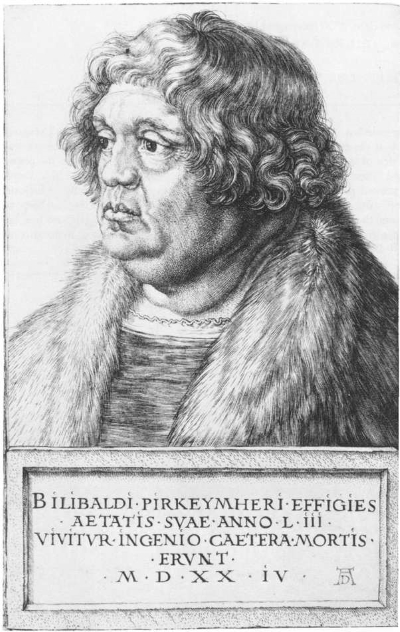

The shining gem within the Arundel collection, however, has to be the library of Willibald Pirckheimer, a German lawyer and Renaissance humanist who was good friends with both Albrecht Dürer and Erasmus. You can see him here, as etched by Dürer:

Willibald Pirckheimer, by Albrecht Durer, 1524 (Wikimedia Commons)

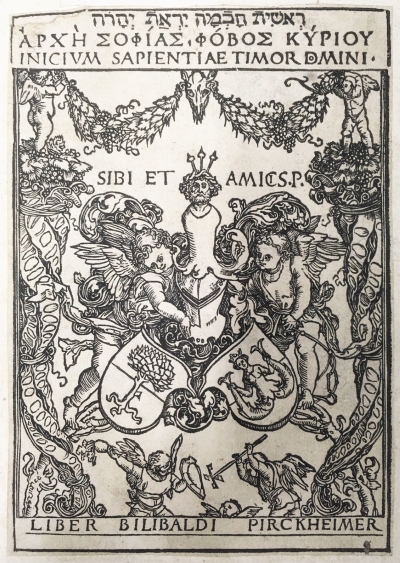

Our old friend the 14th Earl of Arundel bought Pirckheimer’s library almost in its entirety in 1636, while passing through Nuremberg. It’s since been dispersed, part of the continual cycle of books changing hands, leaving one collection and becoming part of another. But something particularly special about these books – and something that continues to tie the collection together, however spread it might be geographically – is the Pirckheimer bookplate. We know that the plate was designed by Albrecht Dürer himself, as a favour to his friend. It bears the phrase ‘for Pirckheimer and his friends’ (‘Sibi et amicis P.’) right in the middle, alongside cherubs, flourishes, the armorial symbols of Pirckheimer and his wife, and what appears to be a couple of angels having a fight. It ties Pirckheimer’s life and his books together.

A Pirckheimer bookplate from our printed books collection

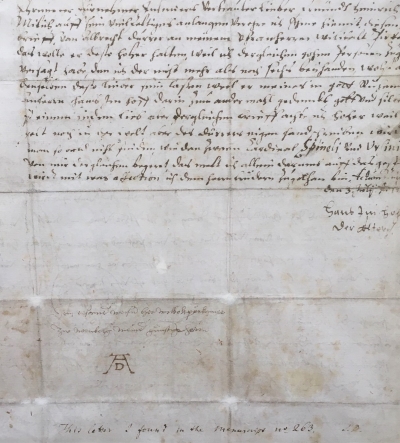

After some detective work, I was delighted to discover that not all of the Pirckheimer collection was sold in 1925, and that we still have books bearing this plate on our shelves. You can find one in an early printed book on astronomy entitled Iulii Firmici Astronomicorum libri octo… (Venice, 1499), for instance. We also have a letter written by Dürer to Pirckheimer (MM/20/59) that was discovered in a codex belonging to Arundel, where he had obviously treasured it. I like to think that these libraries still speak to each other long after they’ve been physically deconstructed, and I hope that in an ever more connected world it’s becoming easier to piece together the stories they have to tell.

Letter from Albrecht Durer to Willibald Pirckheimer, 25 April 1506 (RS MM/20/59)