Complex life is powered by mitochondria; organelles which originated through a unique endosymbiotic event that, about 1.8 billion years ago, changed the history of Earth by enabling the evolution of multicellular organisms.

Complex life is powered by mitochondria; organelles which originated through a unique endosymbiotic event that, about 1.8 billion years ago, changed the history of Earth by enabling the evolution of multicellular organisms. Mitochondria are semiautonomous, retaining their own genome, making it challenging to reconstruct evolutionary dynamics, predict the outcomes of mito-nuclear interactions and coevolution, and find causal links between genotype and phenotype in mitochondrial biology.

The latest issue of Philosophical Transactions B uses examples from a wide array of organisms, including non-model organisms, to discuss how the link between genotype and phenotype depends on evolutionary history, genetic variation and environment. We spoke with the Guest Editors, Dr Fabrizio Ghiselli and Dr Liliana Milani, both from the University of Bologna, about the issue.

Tell us about the idea behind this theme issue and how it came about.

Finding a causal link between genotype and phenotype is a central issue in biology, but it is definitely not an easy task, especially when mitochondria are involved. The nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome have strikingly distinct features and experience quite different evolutionary forces, but they have to cooperate. The great complexity of mitochondrial biology and evolution has been underestimated for a long time, however, mitochondrial biology has started getting more attention from scientists across a wide range of disciplines of life sciences, both basic and applied, including for its role in genetic diseases (once considered rare, mitochondrial disease is now thought to affect 1 in 5,000 people, making it the second most commonly diagnosed, serious genetic disease after cystic fibrosis).

The contributions included in this issue are the result of nearly 3 years of interactions and discussions with colleagues working in the field of mitochondrial evolutionary biology. Most of the interactions happened during international meetings around the world, the last being the “Linking the mitochondrial genotype to phenotype: a complex endeavour” symposium at the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution annual meeting in Yokohama in 2018. We realized that it would be valuable to bring together contributions from colleagues working on different organisms and focusing on different aspects of mitochondrial biology. Philosophical Transactions B was an obvious choice. The acceptance of the proposal was less obvious, but we worked on it, we submitted it, and it went well. We were unbelievably happy.

What do you think is the most exciting idea discussed in the papers?

That is a tough question… Almost everything is new and exciting in this field, and in our opinion each contribution brings interesting data, ideas, working hypotheses, and discussion topics to the table. There is agreement on some points and disagreement on others, but this is the beauty of it: discordance is the engine of science. If we have to find a general idea, a “take home message” from this issue, it would be that it is really important to approach complex problems from different points of view and with multiple approaches. We are convinced that this field has reached a turning point, where new technologies and methods allow us to study a wider range of organisms and to compare the basis of their biological features. Comparative analyses across increasingly large samples of biodiversity are the most powerful approach to understand the evolution and the functioning of organisms.

Liliana Milani and Fabrizio Ghiselli chairing a symposium at the SMBE meeting.

Did you learn anything new when editing the papers?

Absolutely! We read all of the contributions very carefully, and it was amazing the amount of new information we learned during the process. Despite the long time we have spent working on mitochondria, reading, and attending conferences, this experience gave us the opportunity to expand our knowledge, and to get new ideas. In our opinion this is a good sign: it means that the issue is fresh and diverse, and that we achieved our main goal.

How was your experience of being a Guest Editor on Phil Trans B?

Fabrizio: Awesome. Definitely demanding (especially because I was in my last tenure-track year), but really rewarding. It was my first experience as an Editor, and I really liked it. I think I am going to miss it! I would like to thank the Editorial Board of Philosophical Transactions B for allowing us to compile and edit this issue, and for the suggestions they made to the initial proposal. It was a pleasant and formative experience.

Liliana: Really great. As an associate editor of Genome Biology and Evolution I usually have to focus on single manuscripts; here I had to assemble a whole issue, including contributions with different approaches, and forming a project with an integrated identity. I am really thankful for having had such opportunity.

Tell us a bit about your own research.

Fabrizio: I study evolution using molecular biology and genomics and I am particularly interested in conflicts and cooperation at different levels of organization: from molecules to species. I have been working on mitochondria since my second year of PhD, with a focus on the evolutionary and functional genomics of nuclear-mitochondrial interactions. Ants represent a brand-new research line for me; social insects have always been something that blew my mind, since I was very young. Cooperation has always been a tricky subject for evolutionary biologists, and this fact made it even more interesting to me.

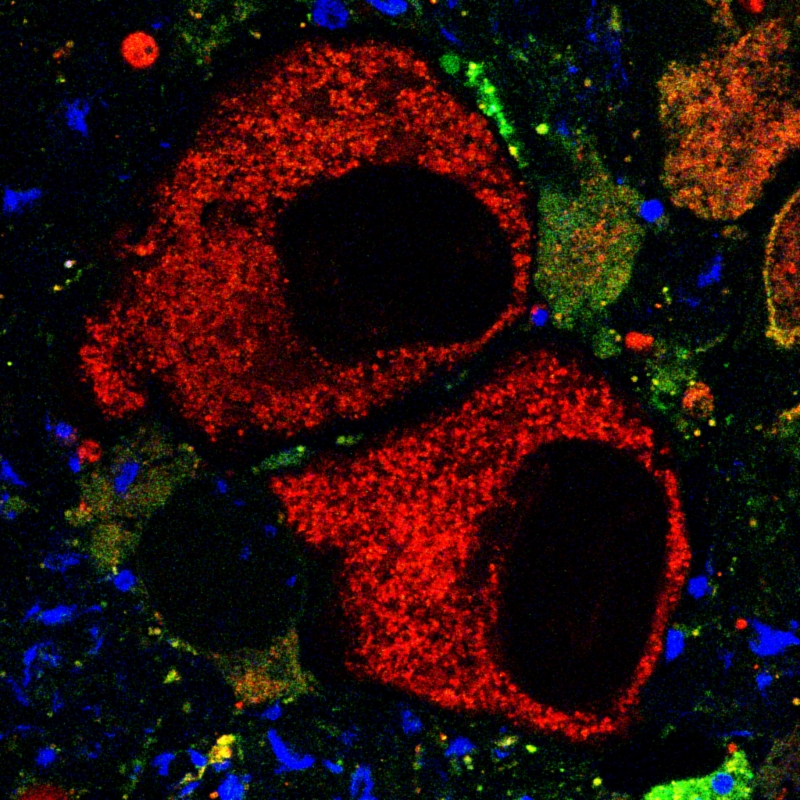

Liliana: I study mitochondrial inheritance and the role of these organelles in germline development, using model and non-model animals, with methods ranging from genomics to in situ localization of molecules. Some mitochondria are segregated into the forming germline, participating actively in its formation, but the molecular mechanisms beyond this process is still largely unclear. Some of the questions I am asking are: is there a mitochondrial phenotype under selection favouring segregation into primordial germ cells? How does this happen during germline development?

If you have an idea for a good topic for an issue of Phil Trans B, find out how to become a Guest Editor.