The Royal Society's Rupert Baker explores the link between the Society, pressure cookers, a village in central France, and St Bride’s Church in London EC4...

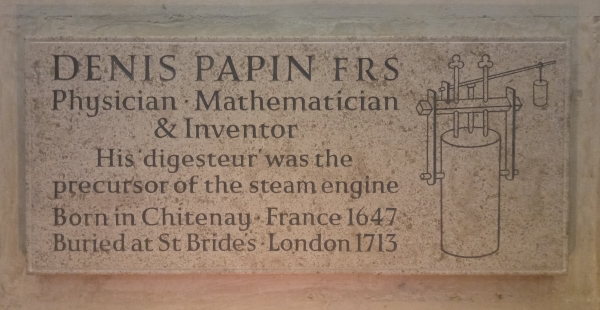

What’s the link between the Royal Society, pressure cookers, a village in central France, and St Bride’s Church in London EC4? The answers are in this picture:

Author’s photo

It shows a plaque unveiled in St Bride’s on 26 February as the culmination of the ‘Papin Project’, a lengthy fundraising, design and public awareness campaign led by Martin Clarke, who currently lives near Vannes in Brittany. Martin has made several visits to the Royal Society Library over the years to research our early Fellow Denis Papin, and was kind enough to invite Louisiane Ferlier and me to the dedication ceremony. Here’s the moment the plaque was revealed to the world…

The unveiling of the Papin memorial plaque, by (L) Derek Rayner, Technical Advisor, Old Glory magazine, and (R) Jean-Paul Nicolas, Secrétaire, Circuit Vapeur Denis Papin, Chitenay. Photo credit: Old Glory magazine

… and here’s a group photo taken a few minutes later. Your Royal Society librarians are lurking on the left; Luke Miller, Archdeacon of the Diocese of London, and Alison Joyce, Rector of St Bride’s, are the ones in ecclesiastical robes. Martin is next to the table, and Jean-Albert Boulay, the current mayor of Chitenay (Papin’s birthplace) is on the right:

Photo credit: Old Glory magazine

So, who was Denis Papin, and what brought him from France to London and the Fellowship of the Royal Society? A very brief, ahem, digest of Papin’s early life runs as follows: born in Chitenay, near Blois, in 1647, he studied medicine at the University of Angers before moving on to Paris as assistant to two Royal Society Fellows, Christian Huygens and Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz. He arrived in London in 1675, working with Robert Boyle and becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society; the precise date of his election, as with many facts about Papin’s life, is not known, but is thought to be at the end of 1680 or shortly thereafter.

Papin was in Antwerp in early 1681, and sent a letter which was read at the Society’s meeting on 2 March, ‘wherein he mentioned his having, before his departure from London, left at Mr Hooke’s lodgings his engine for softening of bones, &c, to be presented to the Society’. This is the device otherwise known as Papin’s digesteur (or digester), forerunner of the pressure cooker and, as the text on the plaque notes, ‘the precursor of the steam engine’. It was put through its paces (presumably by Hooke) at the same meeting:

‘An experiment was made in Dr. Papin’s engine, wherein were put pieces of ivory, horn, and tortoise-shell; all which were in about the space of half an hour reduced to softness; the tortoise-shell to the softness and pliableness of shoe-leather or tanned leather, the ivory to the consistence of old Cheddar cheese, and the horn to the softness and pliableness of pretty stiff tanned leather.’

Papin’s busiest period at the Royal Society seems to have been between 1684 and 1687. Volume 6 of our Register Book contains a long list of experiments he performed for the Society during this time, investigating pneumatics, pressure, volume, and the effects of the digester on various substances. Our archives contain several images of the machine – search for ‘Papin digester’ in our Picture Library for a good selection. Here’s one showing an improved version of the digester, presented to the Society on 5 May 1686 and the subject of a printed book the following year:

Royal Society Cl.P/18i/18

By the time his book of improvements to the digester was published, Papin was on the move again. He spent 20 years in Germany from 1687 to 1707, with fellow Huguenot exiles, before making a final return to London. With old acquaintances such as Boyle and Hooke no longer on the scene, however, this period in London was apparently a less happy one, clouded by disputes with the Royal Society over money and leading to his death in 1713 – precise date, again, uncertain.

Martin Clarke’s research into Papin’s life did, however, turn up a register book at the London Metropolitan Archives which includes a burial record for Papin in St Bride’s, dated 26 August 1713. The ‘Lower Ground’ cemetery where he was laid to rest has long since been built over, but the Church authorities welcomed Martin’s suggestion of a memorial plaque. Several years later, on a beautifully clear February afternoon, we were proud to be part of the congregation paying respects – in English and in French – to Denis Papin.

Do take a look at the plaque if you’re visiting St Bride’s, which is a beautiful Wren church, even if the encroachment of more modern buildings meant that I went through a few contortions to take a picture (below) of the famous wedding-cake spire when I popped into the courtyard after the service. There’s probably a better view from the east, but Louisiane and I had to get back to work, leaving the Chitenay visitors to continue the entente cordiale. We strolled back to Carlton House Terrace with a heightened respect for one of our early Fellows, a true forerunner of the age of steam and the Industrial Revolution.

St Bride’s Church, London. Author’s photo