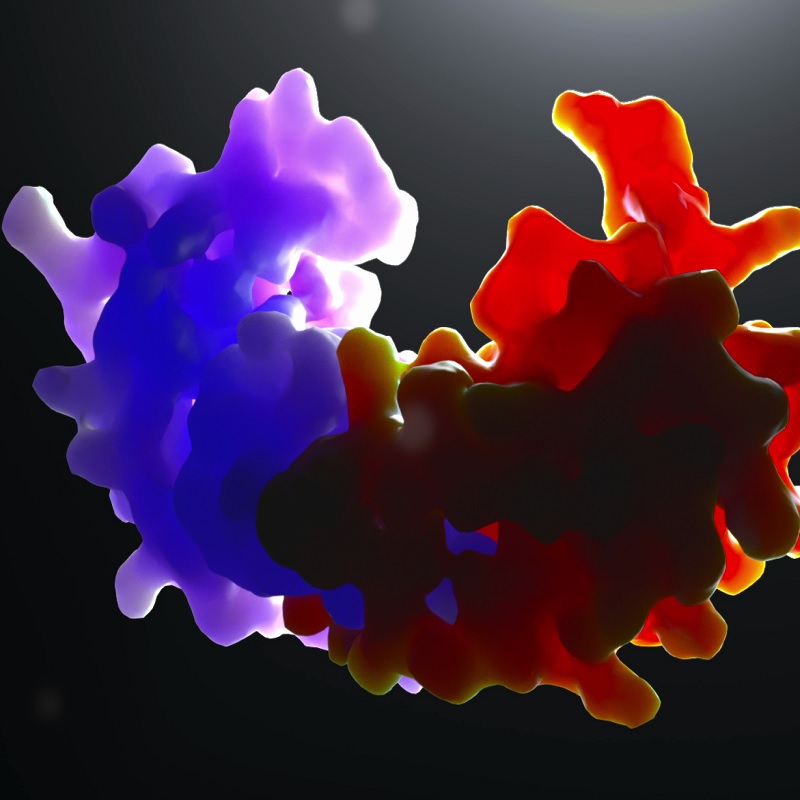

Computational biomedicine uses powerful computers to test our basic understanding of living processes in the human body. Interface Focus has recently published Part 1 of two issues on this topic.

Interface Focus has recently published the first of two issues dedicated to computational biomedicine. We asked the organiser, Professor Peter Coveney at University College London, to tell us more about what computational biomedicine means for patient treatment and the future opportunities and challenges in this field.

Stay tuned for Part 2 which will be published in December 2020.

1. How do you define computational biomedicine?

Medicine is where science collides with life and computational biomedicine can help us understand what this means for an individual patient. In the field we use powerful computers to test our basic understanding of living processes in the human body and, if this understanding holds up, use computer models to help answer the most basic questions asked by all patients: what is wrong with me and what is the best way to treat me?

To put it another way, we are trying to change the point of view of all medicine - and I really do mean all medicine - so that, rather than looking backwards at how large numbers of similar patients tend to behave in similar circumstances, for instance in precision medicine, we want to use computers to look forward, so that we can create a virtual replica of people and use it to create truly personalised medicine.

2. What are the aims of these Interface Focus issues?

Multiscale and multiphysics models are required to recapitulate the human body in all its glory, from ion channels to heartbeats, and, by the same token, we need to bring together people from a diverse range of fields to create multiscale/multiphysics models of a virtual human: mathematicians, computer engineers, molecular biologists, computer scientists - you name it. If the sum of all this effort is to be greater than its parts, it is critical that we join up the dots of the latest thinking across all these fields and these issues aim to do just that.

3. Since you first entered the field, how has it developed?

For this field to advance, we need three things; lots of data, powerful computers and deep understanding. On all three fronts, there have been huge leaps since I started out. We have gone from punched card computers to the first exascale and quantum computers. We are in the era of big data. Although our understanding of the human body, in terms of basic theory, still has a long way to go, you can see incredible progress, for instance in the modelling of the heart, which can now offer more reliable insights that animal experiments.

4. What are the future opportunities and challenges for this field?

Vast new opportunities beckon with the first exascale computers and the continuing rise of quantum computing. The challenges come in many forms. Some are practical, such as the colossal power consumption of exascale machines and gathering, curating, sharing and storing big biological data. Some are cultural, such as the woefully uncritical use of AI methods and the prevailing disdain of theory in the biosciences. Some are profound, notably how to get the best out of quantum computers when some of their most basic properties, notably wavefunction collapse, are not understood. There are also pathologies in digital computation though I believe this challenge is solvable by relying more on analogue computing.

Keep up to date with the latest issues of Interface Focus by signing up for article alerts, and browse previous theme issues on the journal website.

Photo credit: Snapshot from a molecular dynamics simulation of the dimeric form of the epidermal growth factor receptor linked to various forms of cancer (taken from the Virtual Humans IMAX film https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=1ZrAaDsfBYY with permission).