Royal Society Open Science has published its first Science, Society and Policy article, examining the factors that underpin the public’s support of COVID-19 lockdown policies.

This week, Royal Society Open Science published its first Science, Society and Policy paper, The limitations of polling data in understanding public support for COVID-19 lockdown policies. Here, the lead author, Dr Colin Foad, discusses the motivation behind the work and its implications.

In early 2020, when COVID-19 was first entering public consciousness, the idea of democratic governments strictly controlling some of the most intimate aspects of its citizens’ lives was considered so bizarre as to barely even be worth worrying about. Yet, as the use of lockdown policies spread from China to Northern Italy, the idea that such policies were the solution to the problem began to gain traction elsewhere.

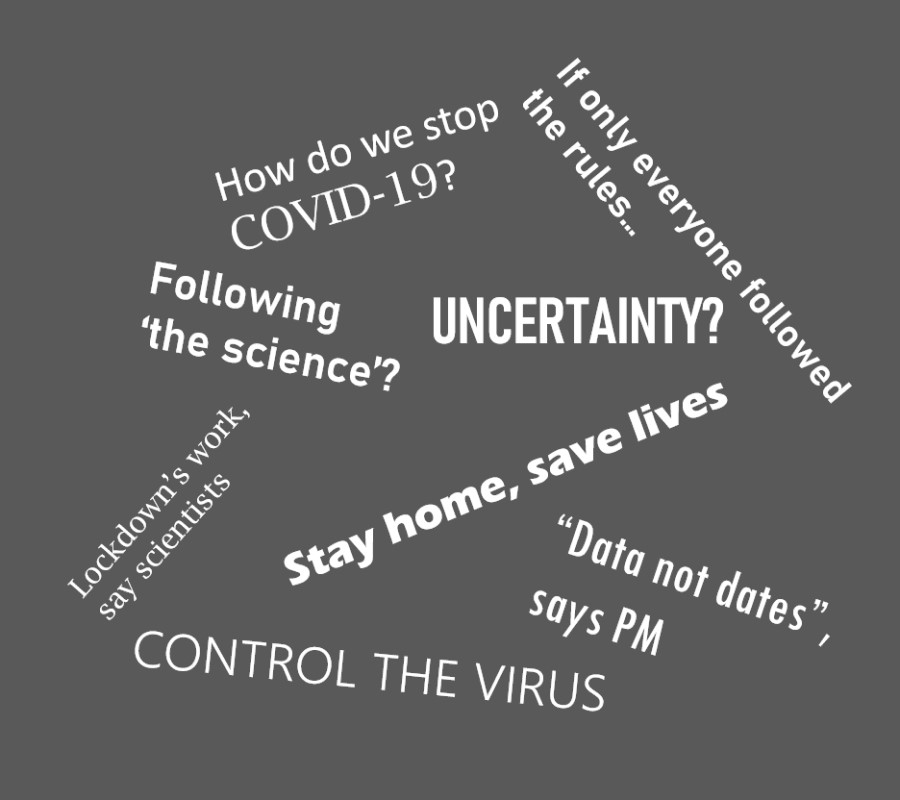

One might have expected that such a massive shift in policy would have been accompanied by a great deal of uncertainty as to the likely outcomes and impacts of such a policy. However, as lockdowns were put in place across the world, such uncertainty was largely absent from institutions (e.g., schools, hospitals, trade unions, businesses, academia), media coverage, and political parties. At the same time, there was consistent polling data showing substantial majority support for lockdown policies. The sheer size of the intervention appeared to simultaneously initiate a certainty that it was definitely the right course of action.

There was of course an understandable appeal for certainty at a time of great uncertainty, and this underpinned the creation of arguably improbable absolutist narratives (e.g., ‘follow the science’). But, as a scientist, this attempt to remove all uncertainty left me with a deep sense of unease. My work is devoted to understanding why people think what they think, and value what they value. I do this because I think such information is critical if we are to make sure that our society more adequately protects the needs of the most vulnerable, using policies that are democratically valued and enacted. But doing so requires recognising that people have complex attitudinal networks that do not always cohere into neat support/oppose positions, and also more broadly acknowledging that uncertainty lies at the heart of most scientific progress.

Two vital things were clear to me from the start of the pandemic. First, independent of their efficacy in slowing the spread of COVID-19, lockdown policies would exacerbate most forms of existing inequality. It is much easier to protect yourself from the worst impacts if you already have power and stability (e.g., financial, employment, housing, education, health). Second, there is no possibility anyone could be certain (or even relatively sure) of the impact of lockdowns, partly because the size and speed of implementation of the policy prevented any such meaningful cost-benefit analysis, and because many of the effects are almost impossible to quantify in terms of what was banned (e.g., the value of a coffee with a friend, mourning at a funeral, attending school, being with your child in hospital), and what was introduced (e.g., how social distancing can encourage people to perceive each other as a threat; the impacts upon children of being continually exposed to COVID-19 architecture in public settings).

My project was designed to fill a vacuum that had appeared at the heart of the pandemic response – we knew what the public thought, but we didn’t know why they thought that way, or if there was any underlying ambivalence in their thinking. In May 2020, I scoped out support from colleagues with relevant expertise and started to build studies that examined how people viewed the difficulties of balancing the harms of the pandemic and its response. I will be forever grateful to my co-authors, and others who supported me, in helping develop this research at a time when asking such questions was not unanimously well received.

I felt a greater understanding of relevant attitudes could be crucial in bringing people together, indicating where people were more conflicted than media narratives often suggested, and examining how people simultaneously care about both COVID-19 and lockdown side effects. My co-authors and I have deliberately constructed our paper in as accessible a format as possible, so I urge you to read it to understand the full context of each finding. However, in general we find that people are clearly conflicted about the implications of lockdown policies, and have been for a long time. Yet, the polling data that tends to appear in the headlines is limited in its ability to directly access this ambivalence.

We also find that people supported lockdown, in essence, because it exists. Without an instant grasp of direct information, such as how case fatality rates differ from infection fatality rates, how the risk profile varies by age, or what age-standardised excess mortality typically looks like, most people quite logically used the information they did have available to judge the threat: i.e., ‘this must be very serious; last month I was going about my business as normal, now I am told to stay at home and stop all non-essential activities’. The sudden jump from normality to lockdown was unprecedented, and so when it came to judging the threat it made sense to presume the size of the threat was in proportion to the size of the policy put forward to deal with it. It is findings such as these that, with further refinement, can help provide some clues about how best to communicate public health threats in future.

I thus urge other scientists to bring their expertise into the realm of understanding public opinion on policy, and I think the ‘Science, Society and Policy’ section of this journal will be seen as a great place to publish work that recognises the complex interplay between these domains. Polling companies can rapidly examine public opinion in large representative samples, but policies are necessarily complex and carry impacts that cannot be easily measured, particularly when examined just in terms of general support. We therefore need to pool our research expertise if we are to better ensure that the complexity and diversity of public opinion is gauged accurately, particularly given the media and government use polling data to guide news coverage and policy respectively.

In sum, there were never going to be easy answers to tackling COVID-19. Initially, simplicity and certainty appeared to be seen as allies in a time of crisis, and they may have helped provide reassurance in the early stages of the pandemic. However, they have their downsides. Simple messaging encouraged widespread adoption of dualistic thinking, which meant the inevitably uncertain information that arose was perceived through lenses of certainty; a process likely further reaffirmed by social norms pressuring others to conform. This polarisation of positions occurred both within and outside science.

As we learn more, we must be more open to embracing this inherent uncertainty, otherwise we risk losing our focus on the broader but less immediate societal damage done by public health interventions. Our data suggest the public are already tuned into this need for complexity. Good science requires humility, and even in times of crisis, uncertainty should be acknowledged, not hidden. Importantly, embracing uncertainty does not mean creating overly complex rules to try and control every element of policy (e.g., the infamous scotch egg debacle), but instead acknowledging that new policies will have unknown impacts, and ensuring people feel free to raise concerns about those impacts. Such public engagement is a critical part of a democratic society. Pretending science has simple answers that can solve any of our public health problems is almost certainly unwise.

Find out more about the Science, Society and Policy initiative in the editorial.

Images: Top image created by Colin Foad; Photo by Vlad Tchompalov on Unsplash.