Scientists through the ages, intrigued by the curious nature of jellyfish, have come up with a variety of theories (and some beautiful art), as Ellen Embleton discovers.

I recently attended my first ever virtual reality exhibition: The Jellyfish. Wearing a VR headset, I found myself transported to an underwater scene, surrounded by a swarm of jellyfish that responded to the sound of my voice, creating – in the words of the artists – ‘a sense of connection with another species’.

The experience was unlike anything I’ve had before, at times a little scary, but also completely enchanting. This was partly thanks to the artists’ skill in creating such a delightful, dream-like scene, and partly because of the inherent beauty of the subject matter.

The nature of jellyfish (the informal name for the medusa-phase of various species of Cnidaria) has long intrigued people, fascinated both by the dangers of their sting and the appeal of their luminescent, translucent bodies. Their beauty, no doubt combined with a somewhat mysterious anatomical make-up – no obvious eyes (although they do have light sensing organs), no central nervous system, no heart, lungs or blood – has drawn many of our Fellows to them as a subject worthy of investigation.

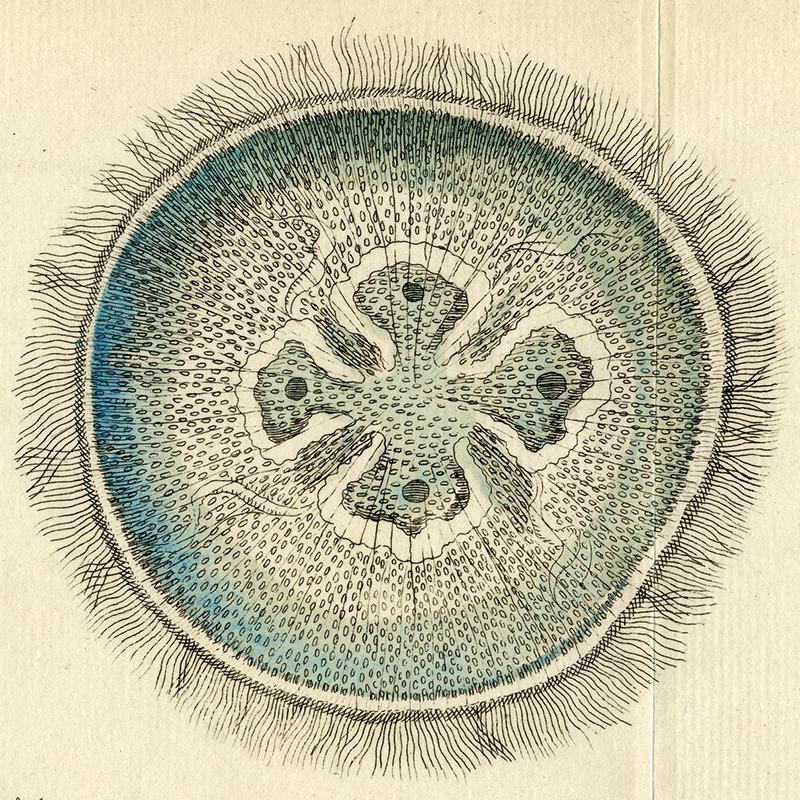

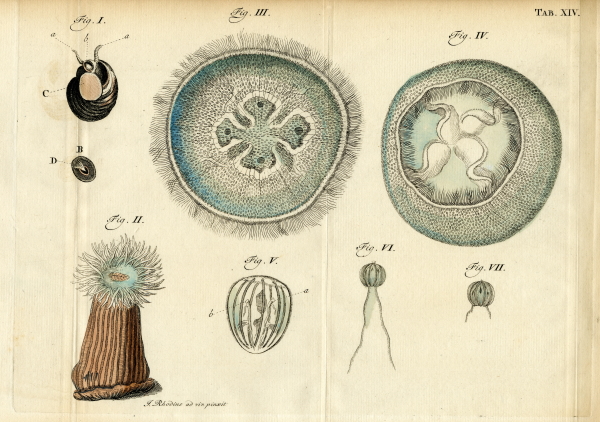

Hand-coloured engraving from Opuscula subseciva (1761), depicting, among other things: a sea anemone (II), and a moon jellyfish seen from above (III) and below (IV) (RS.11814)

Hand-coloured engraving from Opuscula subseciva (1761), depicting, among other things: a sea anemone (II), and a moon jellyfish seen from above (III) and below (IV) (RS.11814)

Above is a plate from Opuscula subseciva by Job Baster FRS (1711-1775) depicting various sea creatures. Baster was one of the first to record the medusa release, which he came across while studying reproduction in cnidarian species. Also known as strobilation, this is the reproductive process by which the polyp-stage in the life cycle of some cnidarians (see figure II of the above plate) buds and produces the medusa-stage (figures III and IV).

Though the two body forms are similar in construction, you’ll see from the above plate that the medusa-phase undergoes some key changes, most obviously the cylindrical body becoming a gelatinous bell. While not all cnidarians undergo the process of strobilation, many do – enough to stump Baster and other eighteenth- century naturalists. A polyp – a sessile body, fixed to the seabed – seems decidedly plant-like, whereas the free-swimming medusa appears closer to an animal. But it can’t be both, so which is it: plant or animal?

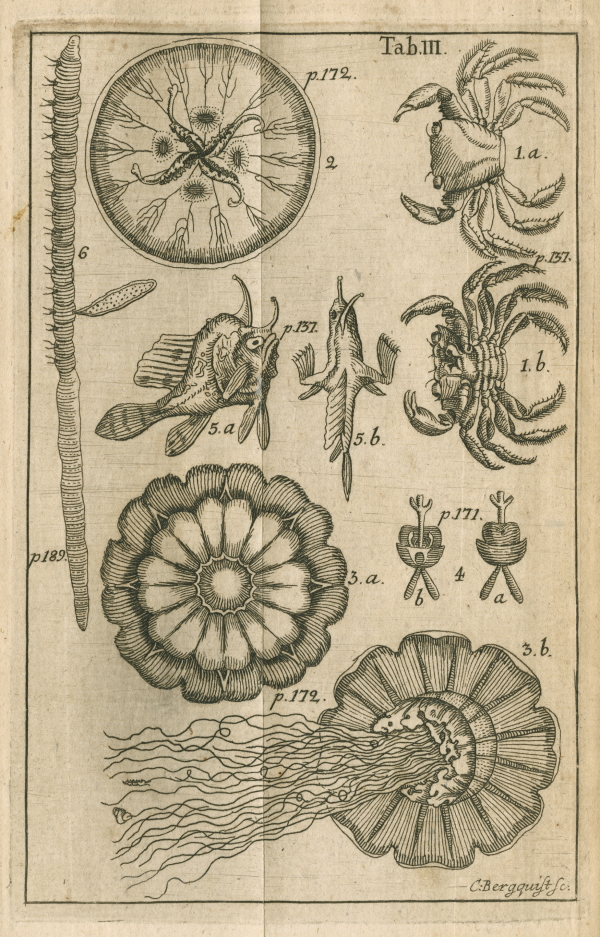

Engraved plate from Linnaeus’s Wastgota-resa (1747), his report of his Government-commissioned travels in the province of Västergötland, depicting an unspecified species of jellyfish (RS.9164)

Engraved plate from Linnaeus’s Wastgota-resa (1747), his report of his Government-commissioned travels in the province of Västergötland, depicting an unspecified species of jellyfish (RS.9164)

In answer to the question mark over the jellyfish’s taxonomic status, Carl Linnaeus FRS (1707-1778), the father of taxonomy, plumped for ‘animal’. However, rather noncommittally, he ascribed it to the genus zoophyla, or ‘plant-like animals’. It took nineteenth-century naturalists, most significantly Charles Darwin FRS (1809-1882) in his famous On the origin of species, to explain the diversity previously observed in cnidarian lifeforms as a result of the process of evolution, spurred on by the power of natural selection.

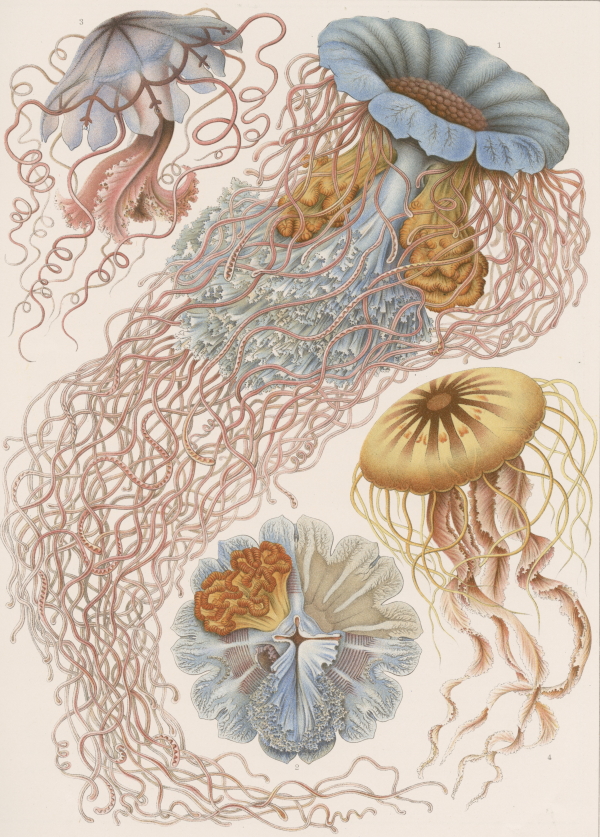

It’s with Darwin in mind that we move on to our next jellyfish enthusiast, Ernst Haeckel (1834-1913), who is said to have sought solace in studying the medusa-phase after the sudden death of his wife Anna in 1864. In need of distraction, he threw himself into the composition of a monograph of medusae which featured over 600 species, two of which he named after his wife – Mitrocoma annae and Desmonema annasethe. Haeckel later had a house built in Jena, the ‘Villa Medusa’, with frescoes of medusae on its walls and ceilings.

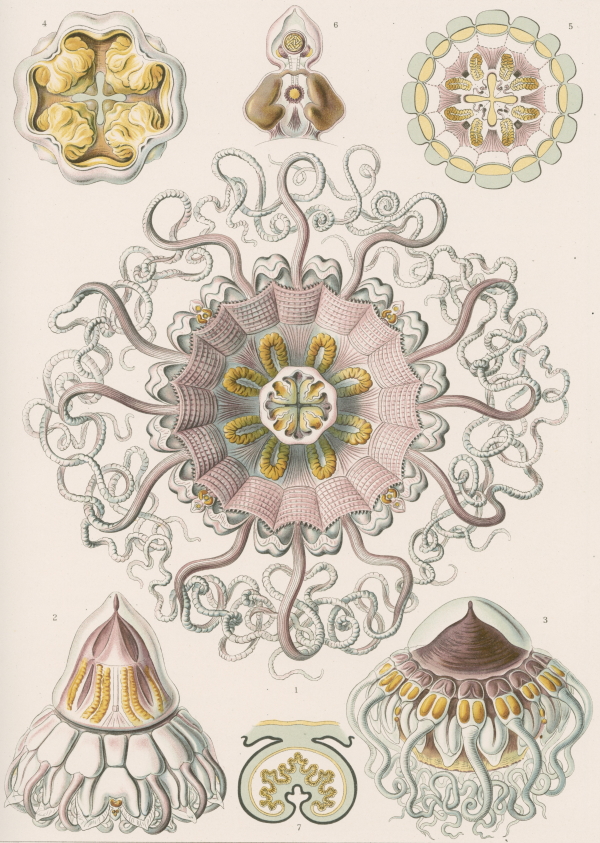

Plate 8 from Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1899-1904). Specimens 1 and 2 are depictions of Desmonema annasethe (RS.9843)

Inspired by Darwin’s ‘family tree’, Haeckel drew up his own ‘tree of life’ to illustrate the evolution of organisms through time, from what he considered the simplest to the most complex. In relation to the jellyfish he explained that, at some point, certain anchored cnidarians, or polyps, took off and evolved in a new direction, birthing the medusa.

Plate 38 from Haeckel’s Kunstformen der Natur (1899-1904) featuring various jellyfish specimens (RS.9845)

But Haeckel didn’t stop there. A proponent of what we would now consider social Darwinism, and a known eugenicist, he took this hierarchical ‘tree of life’ approach and mapped it onto human races. Haeckel argued that the races could be put into categories of superior and inferior, with the Caucasian man at the top and what he referred to as the ‘rudest’ races at the bottom. As a well-known biologist in Germany and elsewhere, and a popular author, it’s safe to assume that Haeckel’s deeply offensive theories were widely circulated, and he played an active role in promoting a racist science.

Just as Baster’s and Linnaeus’s understanding of the jellyfish was shaped by the knowledge and working practices of their era, so Haeckel was a product of his, in more ways than one. Many people might feel torn when confronted with Haeckel’s artworks, and struggle to appreciate them given the darker details of his biography – I know I do. The question of separating art from biography is a complex and subjective one, and we’ll continue to fill in the necessary background where relevant, so that our researchers can come to their own conclusions, on Haeckel, his jellyfish, and beyond.