We catch up with authors of some of the journal’s first papers to discuss their work, then and now.

To celebrate ten years of Open Biology, we catch up with some our first authors and reflect on their research and experience of publishing with the journal. In part one we shared the stories of some of our authors from around the world, including the author of our very first published article.

John Atkins, University College Cork

What first attracted you to working in genetic decoding?

As a non-science undergraduate in Trinity College Dublin I heard a talk on the recent discovery by Crick et al. (1961. Nature 192, 1227-32) of the non-overlapping sequential triplet nature of genetic decoding. I switched to science and graduated in Genetics. In 1968 a fellow PhD. student and I reported in J. Mol. Biol. mutants that caused frameshifting, though it was only later that we identified the variety of mutated translation components involved.

Do you recall how the collaboration for your paper came about? Were there any challenges?

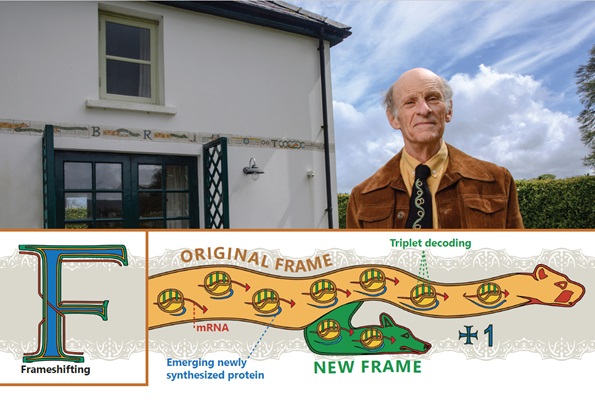

After Andrew E. Firth completed his PhD in Astrophysics in Cambridge University he switched to bioinformatics and did his post-doc on recoding in my lab, before returning to Cambridge University to take up a position in the Virology Division of the Pathology Department. While in my lab, he developed a software called synplot, which he used to discover a number cases of ‘hidden’ functionally important overlapping open reading frames (ORFs) accessed by previously unknown ribosomal frameshifting. Several of these were in viral genomes that had been intensively studied for many years. One of these was in influenza virus. We recruited collaborators and together with them published the functional aspects in an article in Science (2012. 337, 199-204), and the mechanistic aspects in Open Biology.

Suparna Sanyal, Uppsala University

What first attracted you to working in antibiotic resistance?

I was familiar with bacterial infections and antibiotics from my childhood spent in India. For various throat or stomach related infections we were prescribed with antibiotics such as ampicillin or amoxicillin; for skin or eye infections tetracycline and neomycin ointments etc. If occasionally the disease persisted even after taking the antibiotics doses, our family physician would say that the bacteria have become resistant and we needed to try another medicine! That was my first exposure to ‘antibiotic resistance’.

As we grew up, the nature of the common antibiotics changed gradually, and I remember being prescribed for a severe tonsillitis and throat infection during my Master’s exam with azithromycin. By then, I had studied microbiology and became familiar with the grave problem of antibiotic resistance. I focused on ribosomes for my PhD, which are the protein synthesis factory of the cell. Many life-saving antibiotics act by specifically targeting the ribosomes or other components of the bacterial protein synthesis machinery. With this background knowledge I was keen to investigate the molecular mechanism of action of the antibiotics. Why and how do the antibiotics bind and inhibit bacterial protein synthesis specifically? How do our ribosomes escape from being inhibited by the antibiotics despite high level of conservation in the ribosomes across prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells? I believed that once we could answer these questions on the molecular level we would be able to understand and combat the mechanisms of antibiotic resistance.

Do you have any advice that you give to your postdocs/early career students?

Firstly, do not hesitate to ask brave questions. The problem may seem to be very difficult to solve but thinking outside the box is important. Molecular biology research has become very driven by technology. Despite this, the novelty and originality of the project idea play major roles for success in grant applications. You should also keep on publishing. Do not chase very high impact publications all the time but keep publishing in the standard reputed journals at a steady rate. Novelty and merit together pave the path for any early career researcher to get established as an independent PI.

Luisa Capalbo, University of Cambridge

Do you remember what you were doing when the paper was finally published? What were you and your group focused on at the time?

The focus of the research group at the time was to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which the Chromosomal Passenger complex (CPC) controls the activity, recruitment, and assembly of the ESCRT-III filaments during the final separation of the two daughter cells at the end of cell division (i.e., abscission). In particular, we were interested in understanding how abscission events were regulated by Aurora B phosphorylation of the CHMP4 members of the ESCRT-III family.

I do not remember the day that the paper was published, but I remember that I was very happy when the manuscript was accepted because it was my first author paper as a postdoc. I obtained my PhD working part-time just the year before and having a first author publication so soon was exhilarating. My scientific career has been quite unorthodox because I decided to build a family before obtaining a PhD and therefore working in a laboratory as a postdoc was a very significant achievement.

What has been a highlight of your research career so far?

I am currently still working as a postdoc which makes me very happy because working at the bench still fully satisfies me even after so many years working in a lab, something that is probably not very common.

Other papers followed that first author paper in Open Biology as a post doc. I have been working on different aspects of cell division and cytokinesis, but I also had many fruitful collaborations with scientists in different fields.

Open Biology celebrates ten years as the Royal Society’s open access journal for cellular and molecular biology. Find out more about becoming an author and how to submit.

Figure captions

The last larval stage (cyprid) of the barnacle Semibalanus balanoides by Inês Leal. 2018 Royal Society Publishing Photography Competition entry - Micro-imaging Category.

An image of ‘flu virus frameshifting’ from among a band of recoding tiles positioned around the middle of the outside walls of a house in S.W. Ireland. The head motifs used to depict directionality were inspired by the 1200-year-old ‘Book of Kells’ in Trinity College Dublin library. The embedded ribosomes have their A, P, and E sites in green and those shown on the left are at an earlier stage of decoding than those on the right. Correspondingly, on the left the proportion of the mRNA (red) that has passed through the ribosomes is small in contrast to that shown on the right side, and the nascent peptide emerging from the ribosome (blue) is longer on the right side than on the left. ‘Influenza A virus PA is represented in ochre and +1 frame component of the new transframe encoded PA-X product is in green. Credit: John Atkins

Suparna Sanyal – own portrait