Ellen Embleton looks at the ‘thermometer for higher degrees of heat’ developed in the early 1780s by potter and Fellow of the Royal Society Josiah Wedgwood.

Today, the name Josiah Wedgwood FRS (1730-1795) is synonymous with British pottery and invokes an image of two-toned ceramic wares in white and ‘Wedgwood blue’. Recently, I came across Wedgwood’s lesser-known creation, the Wedgwood scale, while reading up on his papers in the Royal Society’s manuscript collection.

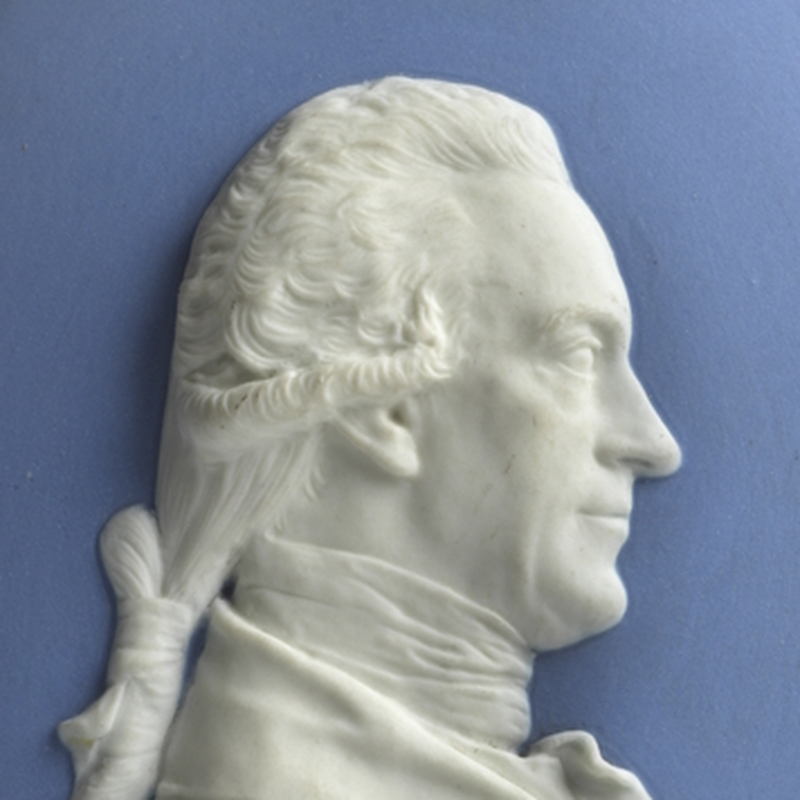

In addition to being a huge artistic and entrepreneurial talent, historians have long applauded Wedgwood for his scientific approach to pottery. Indeed, it was his research into the fine details of his trade that led to his improvements to many existing clay compositions, as well as the creation of an entirely new one, Jasperware, several examples of which are owned by the Society in cameo form: Portrait of William Herschel by Wedgwood after John Flaxman, RS.14166 (left); portrait of Adam Smith by Wedgwood after James Tassie, RS.14165 (right)

Portrait of William Herschel by Wedgwood after John Flaxman, RS.14166 (left); portrait of Adam Smith by Wedgwood after James Tassie, RS.14165 (right)

Prior to his election to the Fellowship, Wedgwood appears in our manuscript collection as a correspondent of Joseph Priestley FRS (1733-1804). Priestley’s letters to Wedgwood (MM/5 and MM/20) relayed the results of a variety of his experiments on ‘dephlogisticated air’, and the effects of heating flint, sandstone, clay and more, all of which would have been of great interest to Wedgwood, given his line of work.

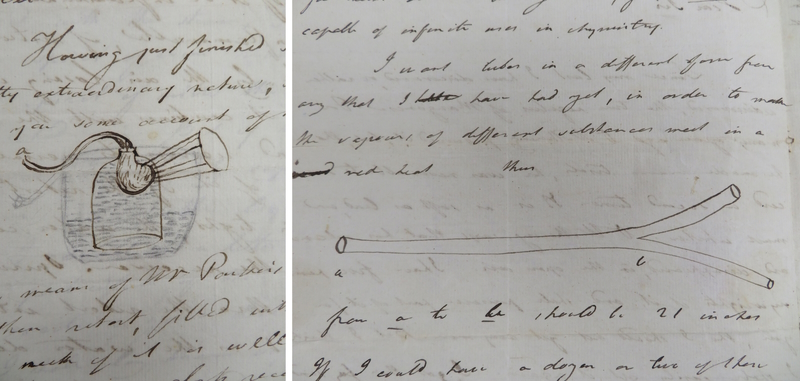

Indeed, Wedgwood appears to have acted as something of a scientific patron to Priestley, supplying him with an annual monetary donation for research and crafting him bespoke ‘philosophical equipment’: retorts, crucibles, and test tubes to Priestley’s design, such as those below. In return, Priestley offered to experiment on ‘earthly substances’ of Wedgwood’s choosing, and communicated Wedgwood’s first paper to the Royal Society.

Priestley’s illustrations of the apparatus needed for his experiments, MM/20/47 (left) and MM/20/48 (right).

Priestley’s illustrations of the apparatus needed for his experiments, MM/20/47 (left) and MM/20/48 (right).

Priestley spoke very highly of Wedgwood’s scientific equipment, writing that his retorts ‘bear the greatest heats that I can give them’ (MM/5/4), and his test tubes ‘are capable of infinite uses in chymistry’ (MM/20/48). He seemed confident that many other scientists would agree; however, there is limited evidence as to the extent of Wedgwood’s apparatus production. Some examples do exist, such as the retort below, and in 1772 Wedgwood published a sale catalogue of apparatus, suggesting some uptake within the scientific community.

Porcelain retort by Wedgwood © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Porcelain retort by Wedgwood © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Wedgwood’s most well documented scientific instrument is his ‘thermometer for higher degrees of heat’. This was a pyrometric device that he developed in the early 1780s to help solve the issue of calculating temperatures above the boiling point of mercury. He wrote to the Society about it in 1780 and 1782. At first, the method involved monitoring alterations in the colour of alum pieces removed from a kiln at varying heats, but by the time of his second paper, he had abandoned this in favour of measuring the diminution in size of clay pieces, which he found to be ‘a more accurate and extensive measure of heat than the different shades of colour’.

Brass Wedgwood pyrometer gauge (left), and Wedgwood pyrometer clay pieces (right) © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Brass Wedgwood pyrometer gauge (left), and Wedgwood pyrometer clay pieces (right) © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

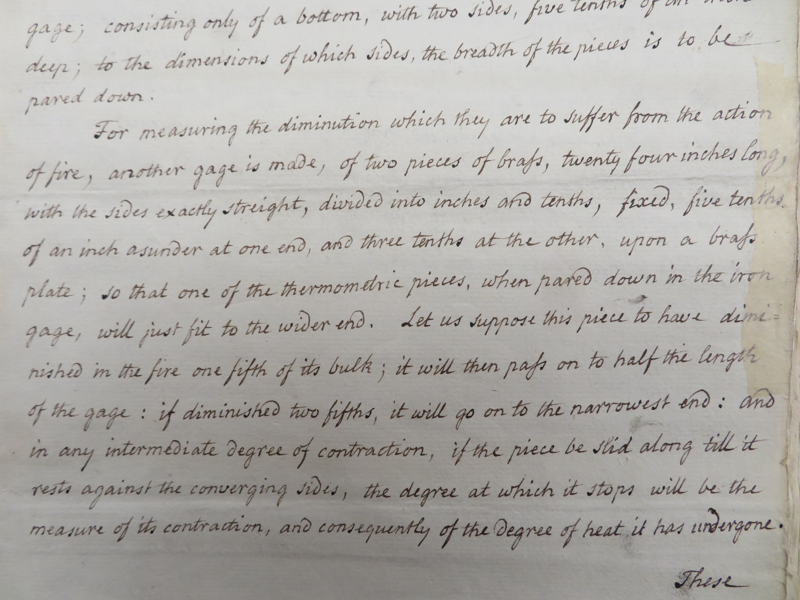

The workings of this later pyrometer are described at length here:

Extract from ‘Attempt to make a thermometer for higher degrees of heat' by Josiah Wedgwood, L&P/7/249

Extract from ‘Attempt to make a thermometer for higher degrees of heat' by Josiah Wedgwood, L&P/7/249

In other words, unheated pieces of clay were moulded to fit the widest gap of a brass gauge, which would give a zero-temperature reading. After heating, these pieces would shrink and fit somewhere between the left and right ends of the gauge. The temperature could then be read from the engraved scale on the gauge – Wedgwood’s scale, or degrees Wedgwood – to deduce the heat of the kiln. This method was published in the Philosophical Transactions.

In a third paper, Wedgwood attempted to reconcile his scale with that of the mercury thermometer of Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit FRS (1686-1736). However, Wedgwood’s estimates in this paper were off, and shortly afterwards concerns were raised about the reliability of his pyrometer method generally. Nonetheless, we know that Wedgwood incorporated the instrument into his own manufacturing processes:

‘This thermometer, which I had the honour of laying before the Royal Society in May 1782, has now been found, from extensive experience, both in my manufactories and experimental enquiries, to answer the expectations I had conceived of it as a measure of all degrees of common fire above ignition.’

The pyrometer clearly played some part in the production of the large quantity of fine ceramics Wedgwood is now famous for. It also arguably secured his election to the Fellowship of the Royal Society, which took place in 1783, so a worthwhile endeavour by all measures!