Louisiane Ferlier describes how specimens sent to the Royal Society by Dutch scientist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek were photographed for our Science in the Making platform.

Later this week, the Royal Society will host a two-day conference and an evening public event dedicated to the Dutch microscopist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek FRS, marking the 300th anniversary of his death. Visitors to our home in Carlton House Terrace will also be able to see a display of amazing instruments on loan from the Royal Microscopical Society, alongside material celebrating Leeuwenhoek and his fellow early microscopists.

Portrait of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, by Jan Verkolje, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (original in the Rijksmuseum)

Portrait of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, by Jan Verkolje, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (original in the Rijksmuseum)

The coverage of ‘Leeuwenhoek 300’ was widespread in the Netherlands, with articles commemorating him as the ‘father of microbiology’ or as the ‘man who studied the wee beasties on his body’ (my loose translation). Events included an exhibition dedicated to him entitled ‘Unimaginable’. To me, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek embodies the very essence of the spirit of scientific discovery that the Founder Fellows of the Royal Society wanted to foster across the world.

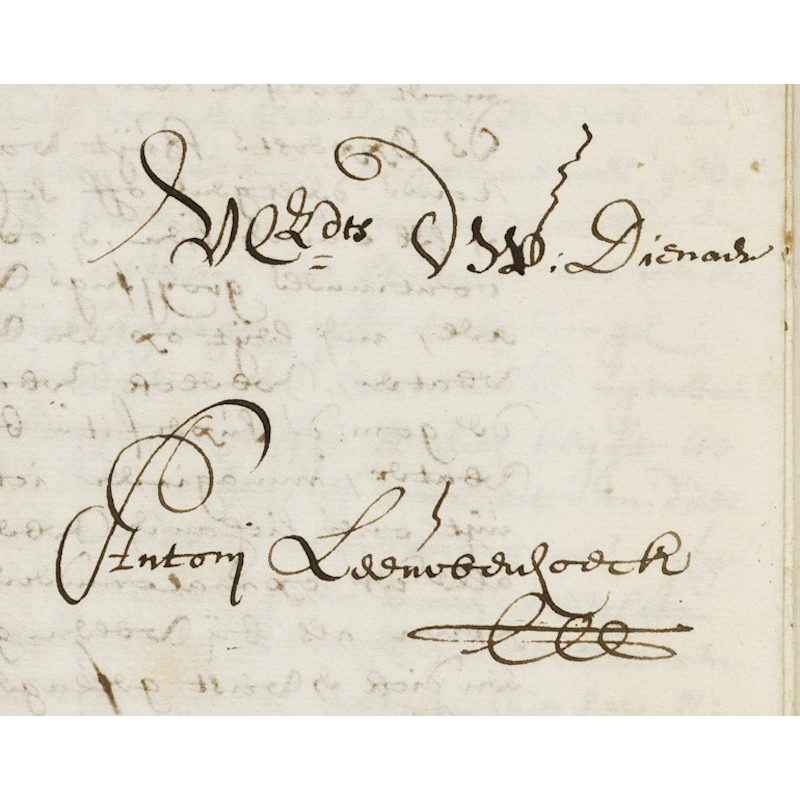

As the story goes, Leeuwenhoek was inspired by the second book published under the imprimatur of the Royal Society, Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665). Upon reading Hooke’s microscopical techniques here, and perhaps in the later Microscopium (1678), Leeuwenhoek was inspired to refine his own methods of producing lenses, and used his microscopes to make discoveries that changed the scientific understanding of biology. Leeuwenhoek also began an immense correspondence with the first Secretary of the Royal Society, Henry Oldenburg, and his successors, detailing his work. In turn, the Society published a large part of the correspondence in the Philosophical Transactions and made Leeuwenhoek a Fellow.

The letters to Oldenburg from Leeuwenhoek were always intended to be shared with the rest of the Fellowship, so they could discuss his methods, analyse his illustrations, and repeat the same observations on the prepared specimens that he sent in order to verify his conclusions.

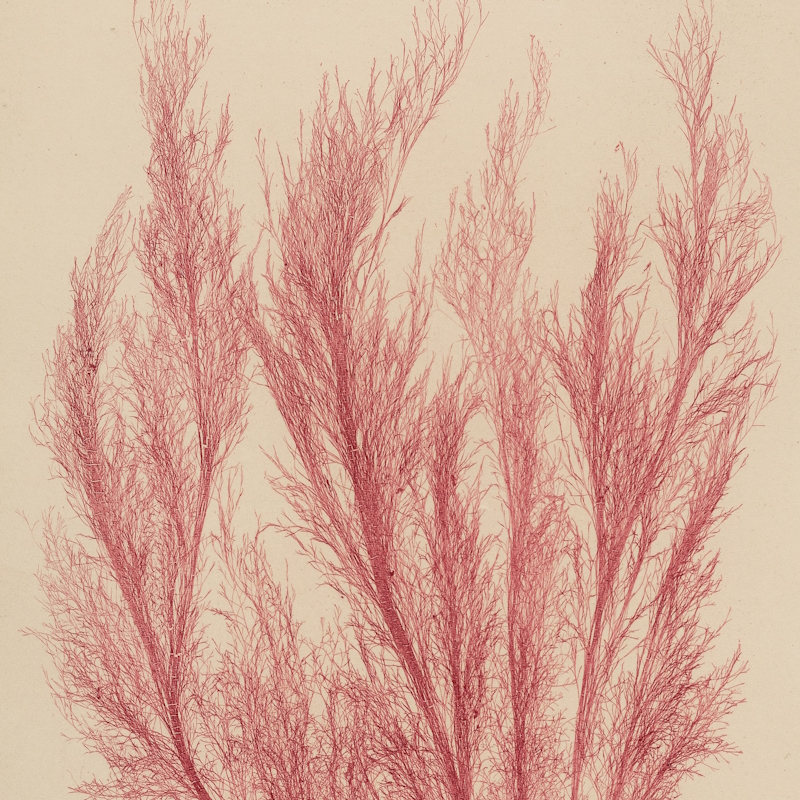

To contribute to this year’s celebrations, we’ve digitised the full correspondence, and I’m now delighted to announce that we’ve also photographed the specimens he sent to the Fellows, with the images now available to all on our Science in the Making platform.

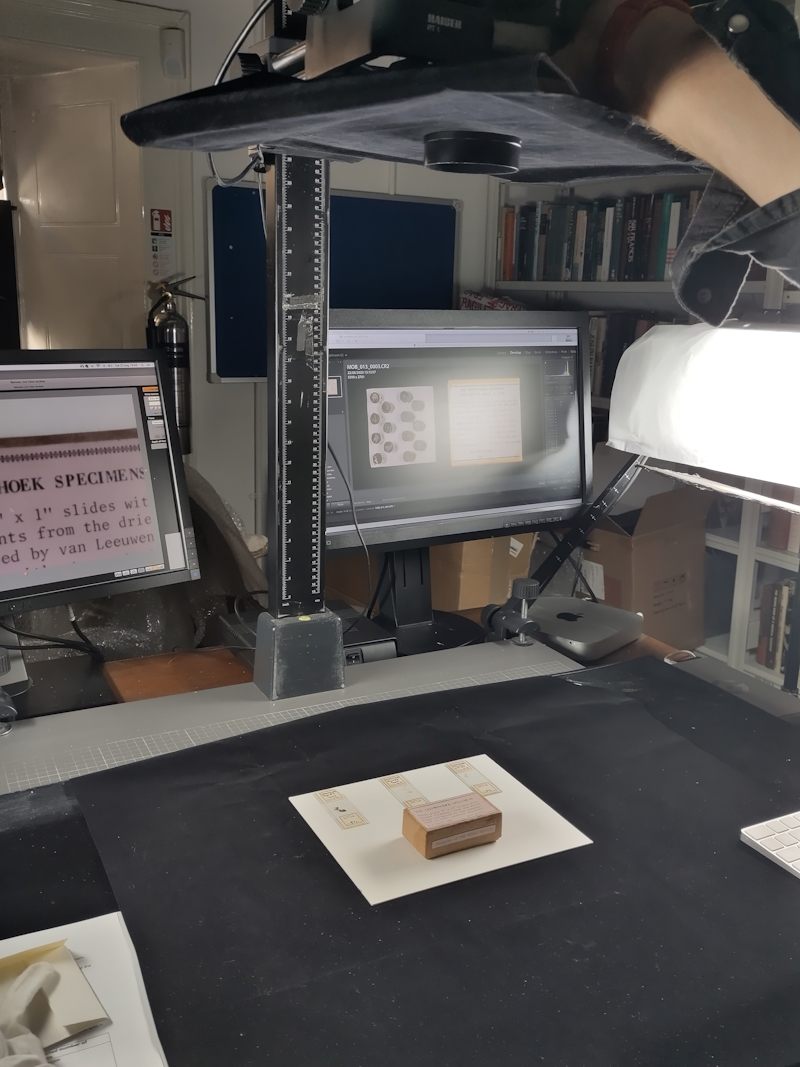

The story of these specimens has already been told by Brian J. Ford, the microscopist who first observed them under an electron microscope. The digitisation I orchestrated is of a very different nature and in no way scientific. Our aim was to reunite the letters and the samples digitally, by photographing the specimens using a DSLR camera, giving us a visual record of the samples in this anniversary year. The photographs will also update our preservation and insurance records. Although our aims were archival rather than scientific, the process was still fascinating.

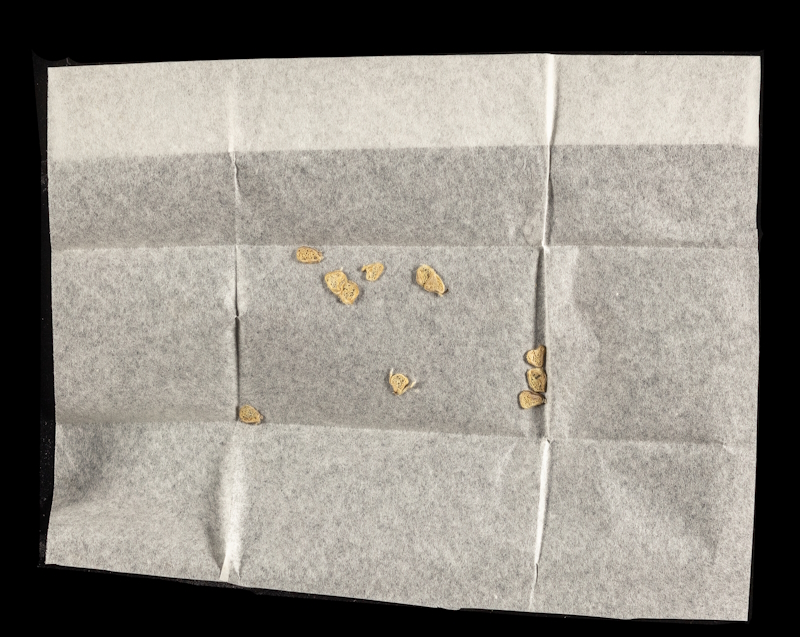

To digitise them in situ at the Royal Society while minimising the risk of contamination and sample loss, I crafted a cradle covered in the black velvet material usually used in our studio. This was intended as a safeguard to contain the specimens in case any fragments spilled from their tiny packets, and to allow a piece of glass to rest over the cradle without touching anything. The glass was treated to minimise static electricity and to avoid reflecting light from the camera.

I then opened each packet in term within the cradle, ensuring that no door could be opened and that neither myself nor our digitisation partner, from Bespoke, could touch the samples, breathe, sneeze, cough or talk over them.

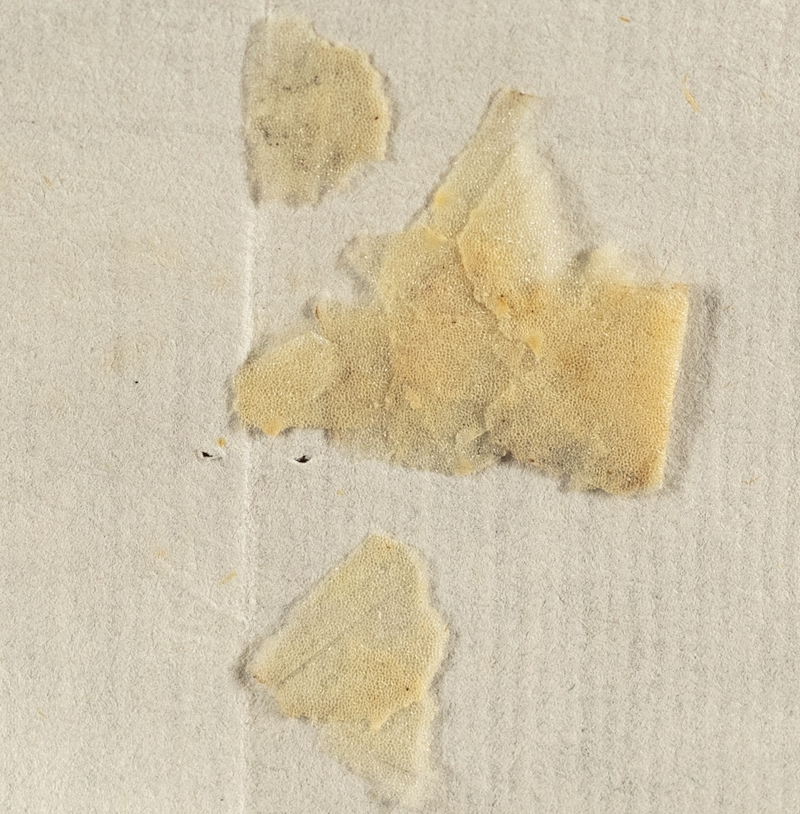

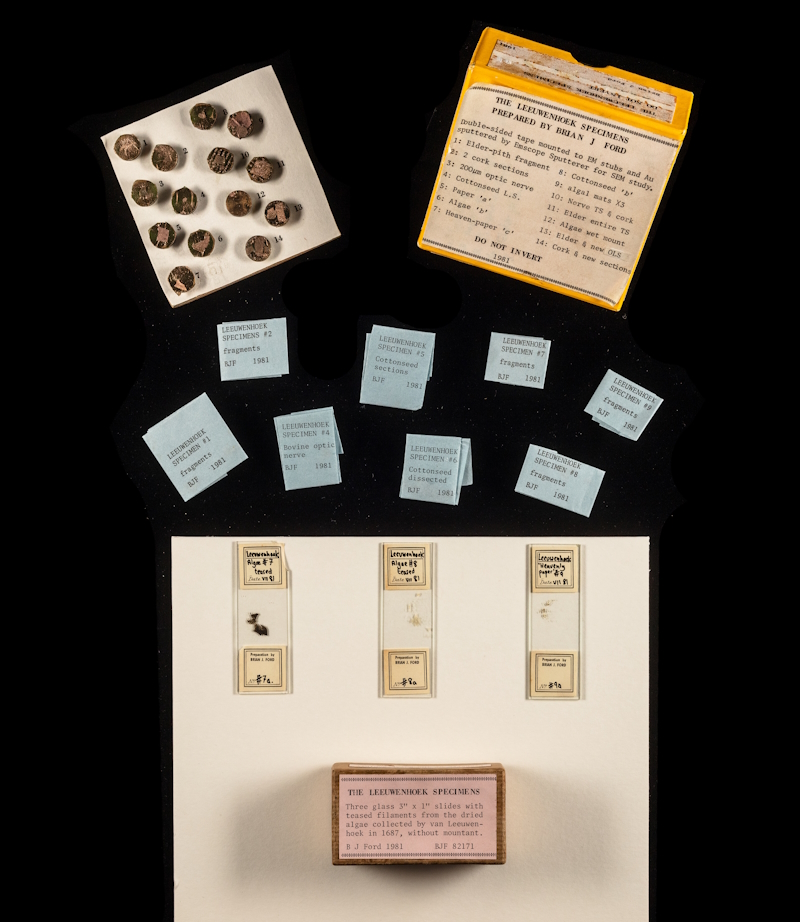

We went through each tiny original packet, and through the portions of specimens that Brian J. Ford extracted and prepared in 1981 for his microscopical studies. Including these specimens seemed essential as they look very different to the originals and now have their own history within our collections.

MOB/013, Leeuwenhoek specimens extracted and prepared by Brian J. Ford

MOB/013, Leeuwenhoek specimens extracted and prepared by Brian J. Ford

The resulting images are fabulous. Although these are not microscopical observations, I hope you’ll agree that the level of zoom is still far beyond what the naked eye can observe. It means that we can now share with everyone the unique beauty that our early microscopist discovered for the first time, over 300 years ago.

We’d love to see you during the conference this week (booking closes at 5pm on Tuesday 12 September). And if you can’t make it, all the letters and the images of Leeuwenhoek’s specimens are freely available online – see, for example, EL/L2/1 and EL/L2/16. As shown in the word cloud below, Leeuwenhoek is second only to Isaac Newton in the most searched terms on our Science in the Making platform – for his anniversary, let’s push him to first place!