Louisiane Ferlier invites you to explore the new online version of an amazing anatomical flap book in the collections of the Royal Society Library.

Some say the history of medicine is the story of autopsies. Certainly, knowledge of human anatomy is a prerequisite for medical treatment: but in historical or cultural contexts where human dissection is forbidden, restricted or discouraged, how do physicians learn about the body?

Today, I’d like to invite you to peel back layers of paper, skin, bones, and time to explore an amazing anatomical flap book in the collections of the Royal Society Library. We’re launching its online version today alongside a public 'Lates' event dedicated to forensics.

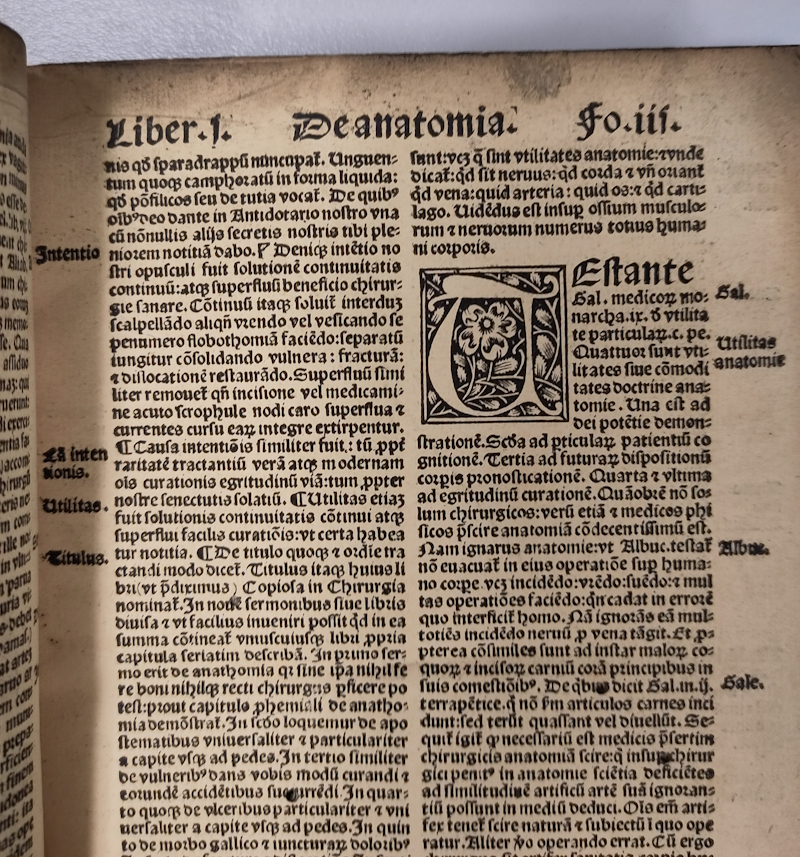

Books on anatomy provided a proxy for opening bodies from the invention of the printing press. As can be seen from some of the early medical volumes in our collections, either they were entirely textual descriptions:

Joannes de Vigo, Practica in chirurgia (1516) R66819

Joannes de Vigo, Practica in chirurgia (1516) R66819

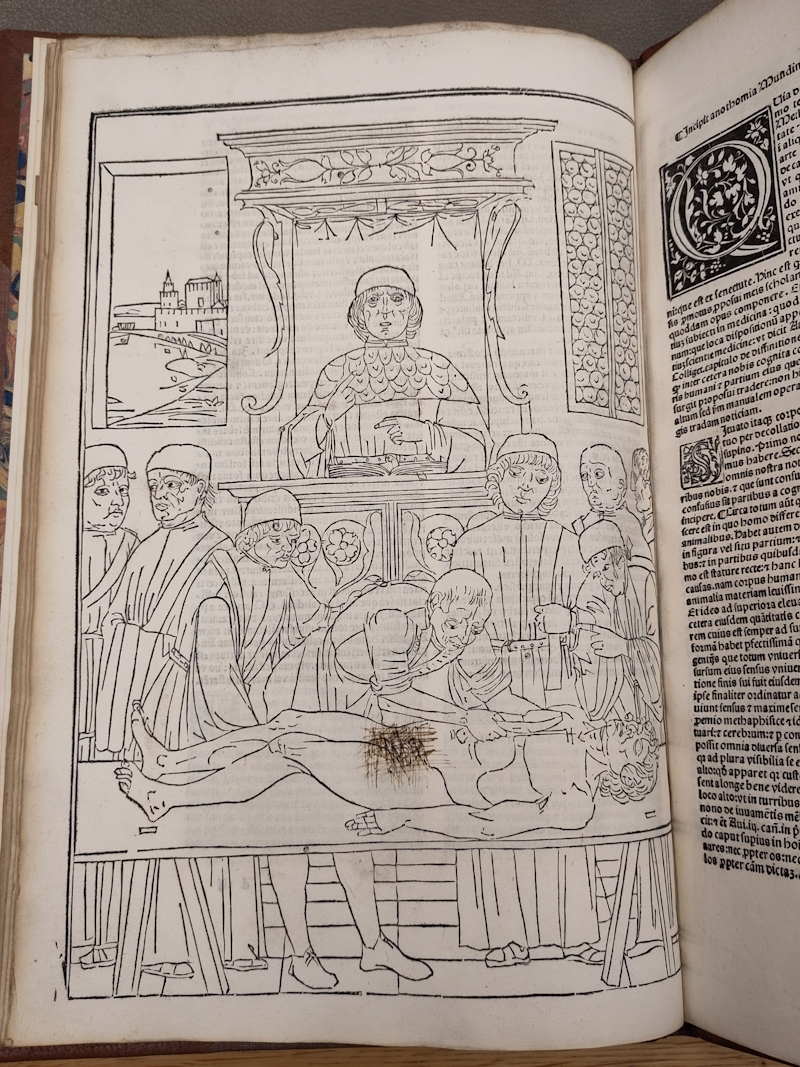

or the woodcut images they included did not show the interiors of the human body:

John Ketham, Fasciculus medicinae (1500) R61021

John Ketham, Fasciculus medicinae (1500) R61021

Everything changed when anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) partnered with some of the best artists of his time to produce the book that changed medicine: De humani corporis fabrica (1543).

Fast forward a few years and authors realised that paper can do more than just support representation – it can also be an interactive tool. I’ve always been fascinated by paper instruments, and as you can see from the selection I laid out for Brady Haran in this Objectivity video, my favourite is this highly complex fugitive sheet, composed of over 100 layers.

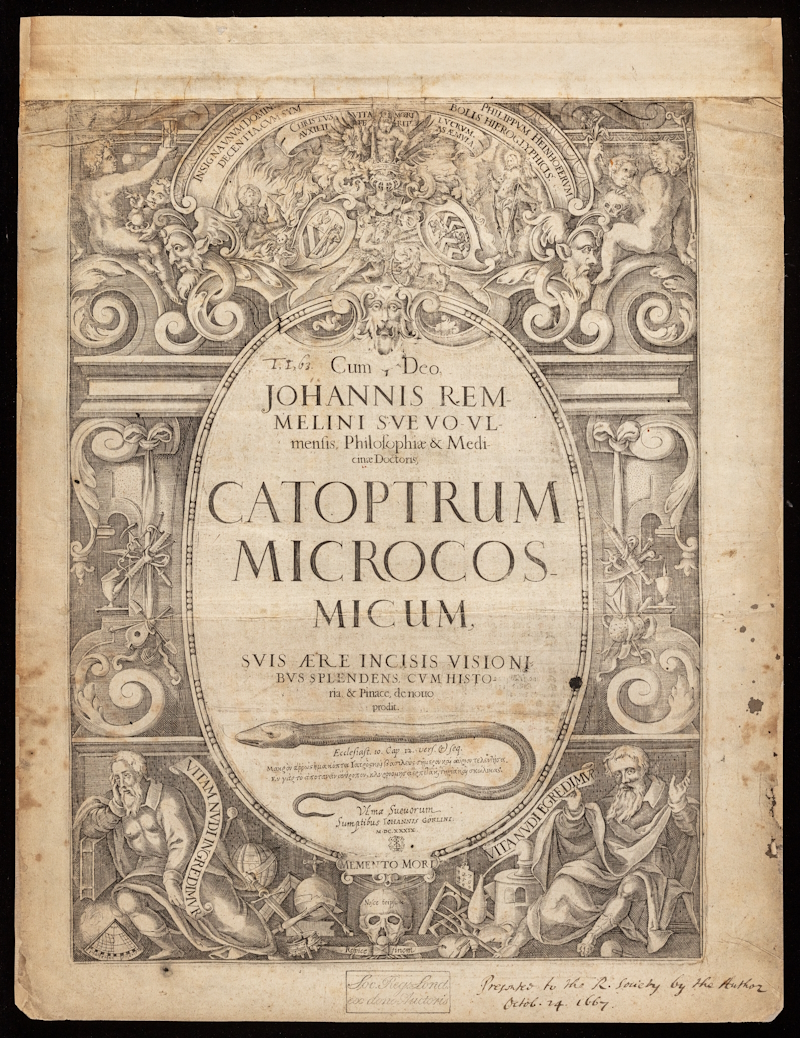

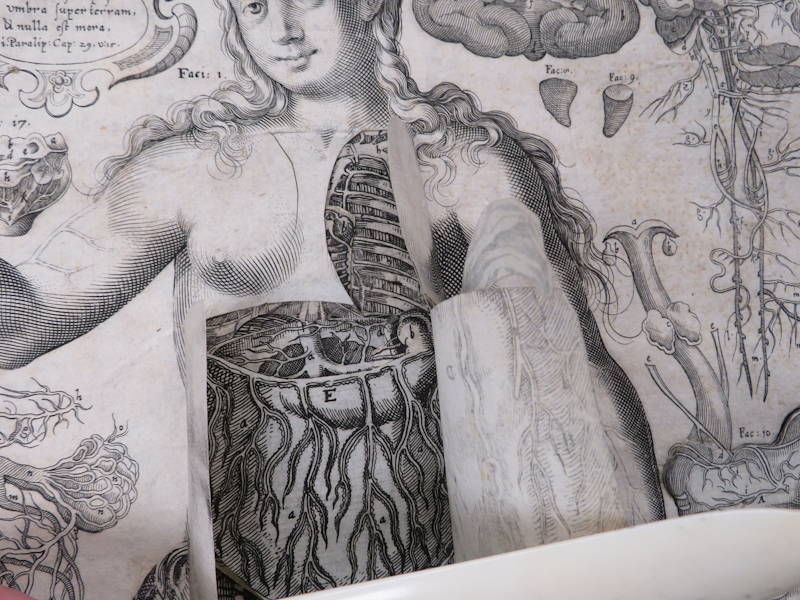

Catoptrum microcosmicum (1619) was created by German physician and anatomist Johann Remmelin (1583-1632) to make knowledge of the human body more accessible. It is thought to have been designed primarily for German medical students, who in the early seventeenth century, worked under limitations in viewing both corpses and illustrated textbooks to learn about anatomy. Such books worked by having each body part engraved on separate slips of paper, and these would be inserted in order into the volume; the prospective surgeon might then gradually lift each piece, to go deeper and deeper into the human body.

Catoptrum microcosmicum, later translated as ‘survey of the microcosm’, quickly became the blockbuster of anatomical flap books. It had more layers than any other and was both a memento mori artwork and a practical tool to circulate medical knowledge. It was rapidly translated into German, French, Dutch and English from the original Latin, and reprinted across Europe. Since piracy is a sign of success, the fact that its illustrations ‘leaked’ on the German print market five years before its first authorised edition proves that the publisher anticipated its importance. Indeed, Catoptrum microcosmicum has been said to be the most successful anatomical lift-the-flap book ever produced.

A 1675 English edition of the work by printer and Royal Society Fellow Joseph Moxon explained how the readership had evolved, describing the volume as ‘useful for all doctors, chyrurgeons [surgeons], statuaries [sculptors], painters etc.’ It is tempting to think that Moxon may have worked from our own Royal Society copy to create his edition, but I’ve found no proof of this so far.

The Royal Society copy dates from 1639 and was printed in Ulm using the original copper plates by Johann Goerlin, who would later produce the first textbook on surgery, Johannes Schulteiss’s Armamentarium chirurgicum (1655). I’ve previously discussed the confusing provenance of the Royal Society's copy, but ahead of launching our digital reconstruction of the volume, I’d like to focus both on how it is built and why Remmelin and his successors bothered to make such a complicated paper tool.

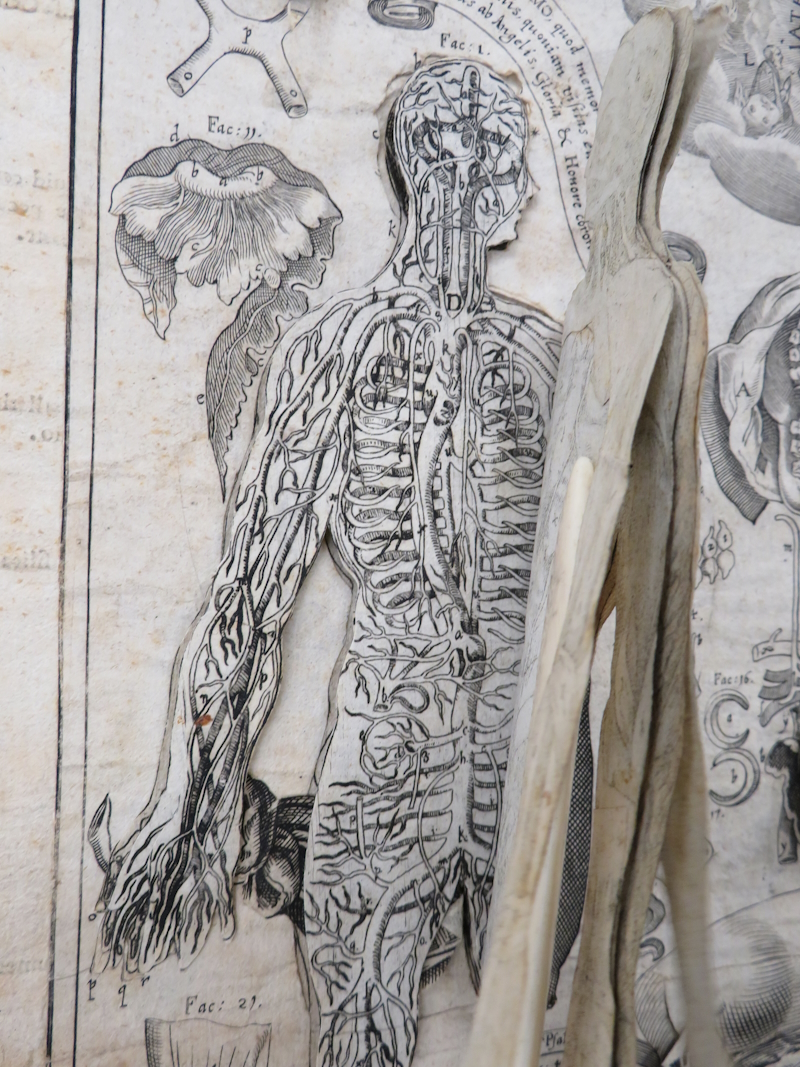

As a technological invention, the Catoptrum microcosmicum is fascinating. Rather than overlaying a cut-out flap over a base engraving, as had been done since the first anatomical flap book in 1538, Remmelin reversed the process to mimic much more closely the layering of the human body and the process of an autopsy.

The top surface of the illustrations, representing the skin, is cut open (as a body would be during an autopsy) to reveal the layers of internal organs. The organs are then inserted into the opening and glued onto a backing sheet. Not all organs were glued, however, to allow the reader or post-mortem examiner to remove some of the organs for closer examination. The fact that the loose organs are still in the book is quite amazing, and it would be fascinating to compare copies in other libraries to check the order in which they are inserted.

The idea behind fugitive sheets was that words alone were insufficient to capture and communicate the essence of the human body. Images were a much quicker and more accessible way of sharing this knowledge with other physicians or students. By multiplying the layers, Remmelin added depth to the experience, and by mimicking the dissection process with paper cuts in the positions that the examiner would use his knife, he was transmitting a manual, physical savoir faire so difficult to put into words.

Arguably, some of Remmelin’s anatomical representations were very approximate even for their time. The memento mori aesthetic, the biblical overtones and the ‘modesty’ coverings (in the forms of sashes, devils and leaves) may also not be to everyone’s taste, but this was ground-breaking 3D paper modelling.

Previous attempts have been made to digitise this very large book, but as the digitised versions either do not include the flaps at all or are composed of still zooms of the flaps in an imposed order, I always felt that they didn’t do justice to the inventiveness of Remmelin’s paper bodies. For the past three years, therefore, I’ve had plans to create an interactive digital version of our copy – and here we are!

An additional unique challenge of the Royal Society copy (as if more complexity were needed) is that it is bound at the top of each page rather than the side, meaning that it opens vertically. This feature was used frequently with large art books, but it prevents readers from accessing the key to the first figure alongside the plate and does not make much practical sense.

Before digitising the volume, it was essential to repair it, and you can see the incredibly detailed and patient work of our conservator in this video. Layers had to be flattened where they had curled due to repeated use, paper had to be cleaned, and tears repaired. The volume had to be disbound and the damaged boards reattached. This allowed us to digitise the pages while they were loose, respecting the vertical opening.

The process of photographing all the different layers was a feat of patience from our digitisation partner and took over three days of shooting and additional retouching work. Finally, the team behind Turning the Pages fine-tuned the technology they developed for the foldouts of Micrographia to facilitate the amazing interactive digital version that I'm delighted to share with you.

It's the first ever digital reconstruction of an anatomical fugitive sheet which recreates online the interaction with the movable paper parts of the anatomical illustrations that the seventeenth century original allowed. The online version gives you the chance to perform your own autopsy of Adam and Eve and see for yourselves the stuff we are (approximately) made of. And do come and join us at the Lates, to celebrate and discover more about the amazing science of forensics.