Madelyn Hernández examines how a diverse array of representations enriched the legacy of the nineteenth-century 'Queen of Science'.

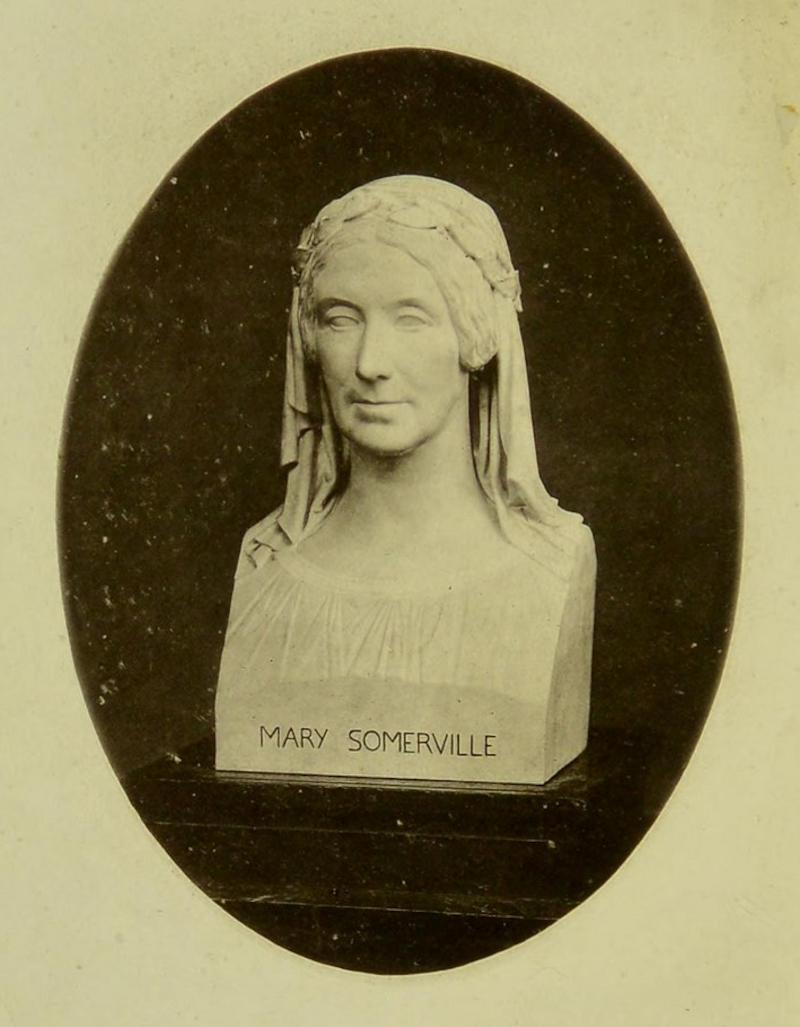

The Royal Society houses a marble bust of the mathematician and writer Mary Somerville. She is portrayed wearing a dress with a wide collar, accentuated by a medallion or brooch. Her hair is meticulously styled, pulled up, and fashioned into ringlets on both sides. It's a remarkable representation.

My fascination with this sculpture is intertwined with my research interests, which lie in the intersection of women's history in science, the history of books, and the impact of visual representation on the scientific landscape. While engaged in a research trip funded by a Royal Society Lisa Jardine Grant, I started to think about how images of Somerville contributed to the creation of her public persona, one that celebrated her as the 'Queen of Science' during her lifetime. The sculpture, commissioned by the Fellows of the Royal Society and the first representation of a woman to be displayed on the Society’s premises, played a crucial role in this process.

Marble bust of Mary Somerville (RS.11063)

Marble bust of Mary Somerville (RS.11063)

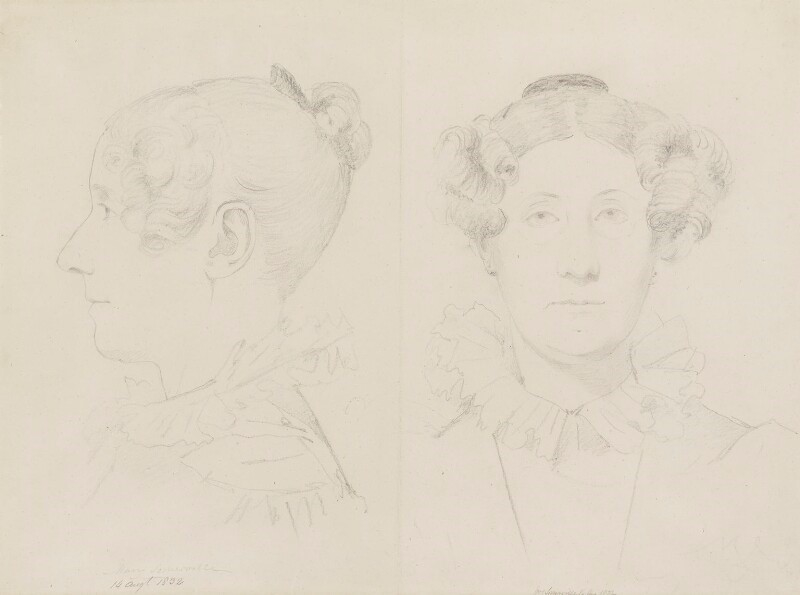

The bust was commissioned in 1832, months after the publication of her English translation of Laplace's Mécanique céleste, entitled Mechanism of the heavens. Mary Somerville had already garnered considerable recognition among a select group of intellectuals who esteemed her as a brilliant mathematician, even before the publication of this work.

The realisation of the marble bust, however, carried significance as it legitimised her work and her identity as a woman in science. The Royal Society wanted to pay tribute to ‘the power of the female mind – and at the same time establish an imperishable record of the perfect compatibility of the most exemplary discharge of the softer duties of domestic life with the deepest researches in mathematical philosophy.’

The artist chosen for this task was Francis Leggatt Chantrey, himself a Fellow of the Royal Society and known for his skill in creating portrait sculpture busts. Chantrey's meticulous attention to detail was particularly evident when he aimed to convey the intellectual attributes of his subjects. His portrayal of Mary Somerville introduced a duality in her image: the combination of femininity and intellect, harmonised in one person. So although there was a feminisation of the figure of Somerville, it also expressed the encouraging prospect of an intellectual life for women.

Various reasons initially led to the postponement of the sittings for the sculpture. However, they were eventually carried out in 1834, shortly after the publication of Somerville’s second book, On the connexion of the physical sciences, which proved to be a resounding success.

Chantrey's studio served as the home for the evolving bust, where it was meticulously perfected over the years. The transformation of the bust from initial drawings to its final form was observable as various visitors to Chantrey's studio praised the accuracy of the likeness. The bust was also presented in the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1837.

Preliminary drawing for Mary Somerville’s bust, by Francis Chantrey, pencil, 1832 NPG 316a(114). © National Portrait Gallery (Creative Commons Licence)

Preliminary drawing for Mary Somerville’s bust, by Francis Chantrey, pencil, 1832 NPG 316a(114). © National Portrait Gallery (Creative Commons Licence)

Following Chantrey’s death in 1841, the Treasurer of the Royal Society finally presented the bust in 1842, in the names of His Royal Highness the Duke of Sussex and the contributors to a subscription fund to pay for the work.

On 14 March 1844, a letter from the sculptor Frederick Scott Archer was read to a Council of the Royal Society. It conveyed the wishes of several Fellows, including notable figures like Captain (later Admiral) William Henry Smyth, John Lee and Francis Baily, who wished to possess casts of the bust. Their request was approved, provided it did not harm the original sculpture. These casts circulated in England and beyond, contributing to a further layer of recognition and legitimisation for Mary Somerville.

Moreover, additional portraits and images played a pivotal role in shaping Somerville's public image. For example, a portrait by Thomas Phillips, painted in 1834 and commissioned by her publisher, John Murray, found a place in the exclusive surroundings of Murray's establishment. While this was inaccessible to the general public, the painting also went on show at the Royal Academy.

Mary Somerville, by Thomas Phillips, 1834. Credit: National Galleries of Scotland, Creative Commons CC by NC

Mary Somerville, by Thomas Phillips, 1834. Credit: National Galleries of Scotland, Creative Commons CC by NC

Another prominent representation of Somerville was a bust by Lawrence Macdonald, which was copied several times. It even made its way to America, where the astronomer Maria Mitchell obtained a plaster cast of the Macdonald bust through Frances Power Cobbe. Mitchell proudly displayed the likeness of Mary Somerville in the Vassar College Observatory, serving as a reminder of how women could make significant strides in the field of science.

This bust was transformed into an engraving and featured as a frontispiece in the seventh edition of On the connexion (1846), and in Personal recollections, from early life to old age, of Mary Somerville (1873). The circulation of frontispieces featuring author portraits contributed to a growing fascination with authors' lives.

Engraving of the bust by Lawrence Macdonald (Wikimedia Commons)

Engraving of the bust by Lawrence Macdonald (Wikimedia Commons)

This diverse array of representations enriched the legacy of Mary Somerville and played a pivotal role in her recognition and influence, both within her lifetime and as an enduring inspiration for women in science.